In the past week I have confronted the sentiment that “poetry is dead” in two different, but somewhat related contexts. Is it only the contemporary that has birthed an obsession with such apocalyptic telos? There is a certain thrill - the same kind of thrill associated with an electrical spark apprehending darkness, or the magic of technology - associated with the perceived privilege of having the foresight to see the death of a thing, the “end of an era”. Commentators, not domain experts, are caught in the embrace of this dramatic anxiety about such futile questions as “the future of art” and “the decadence of the age”. Poets don’t worry about this. We are busy in the pursuit of that which disappears; our poems, merely shadows shimmering in the walls of a cave. We endeavour to channel our death drive into the page. The practising poet’s relationship with the form is secure in the curiosity for the unknown. The question is often asked, of AI, for instance -if technology builds only on what has preceded it, the data that it surveys, how will it curate the ‘new’? This is supposed to be the problem of the algorithm, that is also at the systemic core of echo chambers.

To come back to the question at hand, popular opinion posing as a spokesperson for critical scholarship has had a tendency to prophesy the death of culture. Sample an extract from the recent New York Times article, Poetry Died 100 years ago this month: “This seems to me true for the simple reason that poetry is dead” (The nerve of the fellow) and then, the vainglorious clincher: “Indeed, it is dead in part because Eliot helped to kill it”. This attempted surgical strike, embroidered with spectacle, is meant to unsettle. It happens ever so often - I have heard it repeatedly in three different domains of representation: Music, Art, and Poetry. Don’t get me wrong. I am not speaking about an academic interest with the question of death in society. I know a scholar whose eyes light up at the sight of this morbid design - a kind of darkly humorous fascination with the affective intensity of the event, as cultural and social. That kind of interest sees death itself as a living entity. Its optimism is fuelled by curiosity.

The kind of naysaying that the above article is wallowing in, however, is forged from a fragile certainty of power that finds itself to be tottering. Taken to the extreme, this insecurity is no different from the ‘fear’ of the tyrant in Gorakh Pande’s Unka Dar.

In response to a tweet about this article by the poet Vivek Narayanan, Rahul Santhanam tweets: “Why this lack of desire? Perhaps because of the illusory stability of the pernicious category known as "the West", with all its concomitant dreams and nostalgias”.

My guru, Ustad Zia Fariduddin Dagar, would start laughing when people told him “Dhrupad is Dying”. He would say, Beta, tab se sunte aa raha hoon, jab se maine gaana shuru kiya (I have been hearing this since I started singing). One student is enough for the tendril to grow into another forest - the ‘tradition’ evolves. But it is worth asking, as Santhanam does, about the author who’s prophesied the death of poetry: “Why this lack of desire?” Is it simply the egotism of cultural centrism, the imperialistic urge for definition and desecration?

Let me turn the other experience to look for an alternative response to this question.

A few days ago my friend announced with all the bombast of a summer breeze - “You’re finished bro. What poetry and all? Tell what you want, you want love poem aa?” Then he vanished into his laptop typed a single command, and voila:

Apart from the fact that this amazing piece of technology seems to be aligned more with Chetan Bhagat than Shakespeare or Kalidasa (or even early Prakrit, Sangam poets), it has done something extraordinary. In one shallow swoop it has shown that the human relationship with knowledge (From “What we see” to “what we know”), even in its most creative, has barely skimmed the surface. While the world is going mad with the possibilities of this latest manifestation of intelligent machine life, the paradox of this pursuit can be resolved only through the human mistake of epiphany. A new path is born, not in the secure home of the observer, but in the adventurous foray of the artist, or the lover. We must not imprison poetry with a cultural relativism that seeps further into moral authority. Hold Everything Dear.

We cannot be afraid of the old and the original. The burden of experience, and form, sits lightly on the dancing fingers of the passionate and the wild. Each time a poet confronts a feeling without a name they find language anew. We search everyday, for the light, not knowing that, as polyglots we make and unmake our own worlds. Who says there is no god?

Divinity sits elsewhere. It starts in the acknowledgment of the impossibility of foresight. On the one hand, we have Anthropologists and Colonisers making woke apologies for upending homes of millions, first hunting down, and then appropriating entire cultures, and on the other hand, we have this - people who worry about the death of poetry. Ambedkar advised against this kind of moral high-grounding - we must ask questions of our own privilege in the first place.

The beauty of desire is that it never reaches the object of its own becoming. It connects and interlocks, yearning for absolution. But release is fickle, short-lived - only until the next ridge of longing, the inevitable plateau of emotion. I have my doubts about whether a computer programme, manufactured from the human intellect could reach this place of intuition organically.

I share with you today, three unrelated poems. The first, by Linda Gregg, continues the conversation on desire.

Gregg’s desire is not blasphemous. There is a place for that - for the breakdown of the sacred, where the poet turns sacrilege into craft. This poem, however, is doused in wonder. The sense of the sublime is not compromised by maturity. Her wisdom flits between that which is outside the horizon of ‘human’, and an acute self awareness of the ‘flesh’ - the body. The poet sits at the edge of deliverance, gently nudging a self shot through with sensation. Even empathy is a place that is alive through nostalgia. With the eye of care that turns the ordinary into miracle, she hesitates, unsure, momentarily, of the attire with which she meets the world. The final volta relocates the self within space, as place. Her language is gentle, but filled with awe.

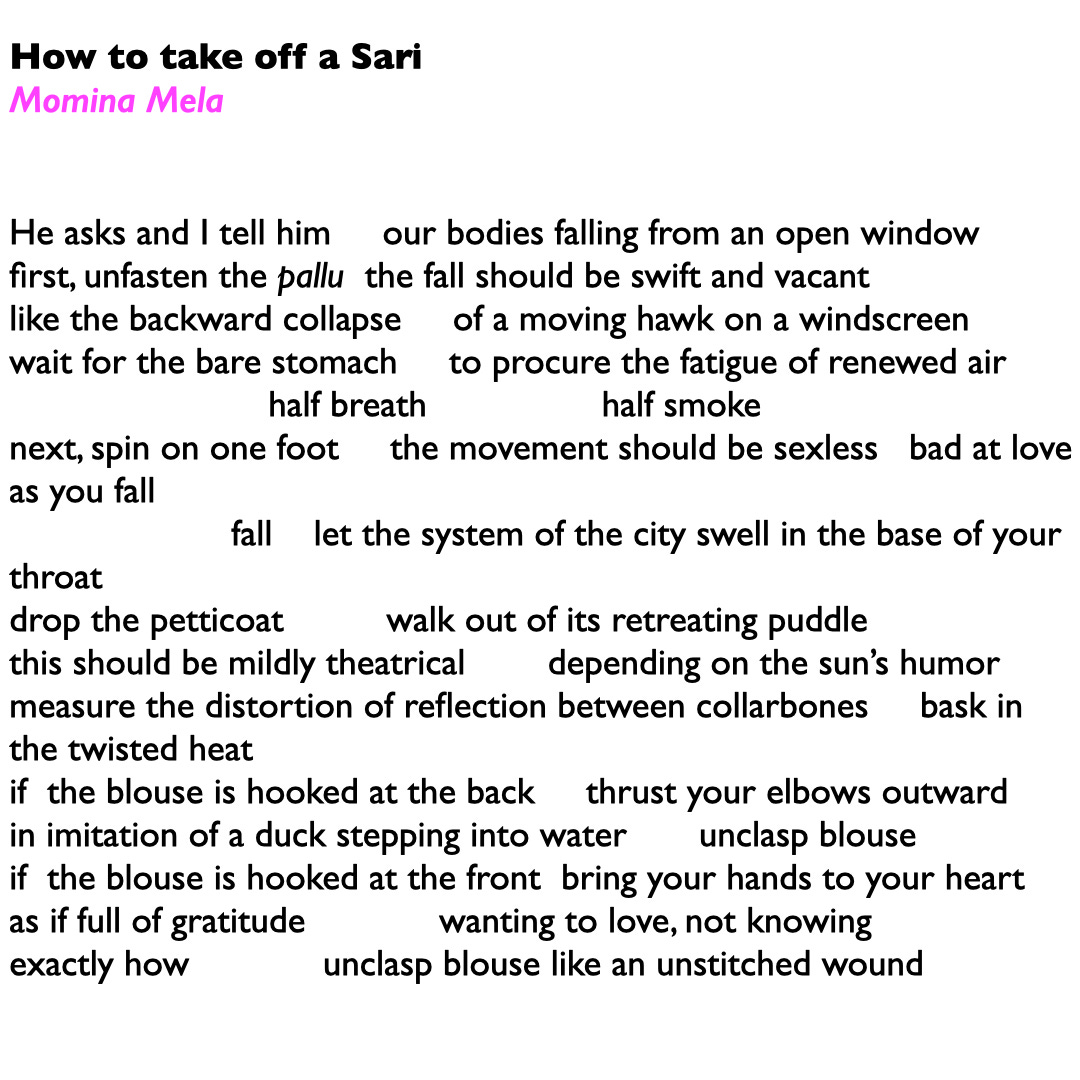

Gregg’s playing field is love, and nature. It has not reached eros. For that I turn to an old favourite, by Momina Mela, that has, incidentally, been published in the print edition of the April 11, 2016, issue of the New York Times.

Sigh. Like an unstitched wound. This is love language. How the syntax of union is cast in the mould of rupture! The erotic birth is marred by a rapturous wound. The poet verbs into the ritual act of undressing before making love, and in that intimate encounter, the lover’s fall is passionate. The mundane, again, is present only in service of the suggestion of complete surrender - the stuff of romance. It is a tale told without inhibition, a heady matter-of-fact utterance. This erotic manual balances wit with metaphor, avoiding the pitfall of turning the everyday into parody.

This is new language, lurking between the synaesthesia of touch and speech.

The poet is concerned with that which comes after. The observer looks askance, not simply at the object, but at the shadow it casts. In that shadow, lives the truth of the object’s birth, and the clues of its future. It is a truth that continuously evolves - that makes and unmakes.

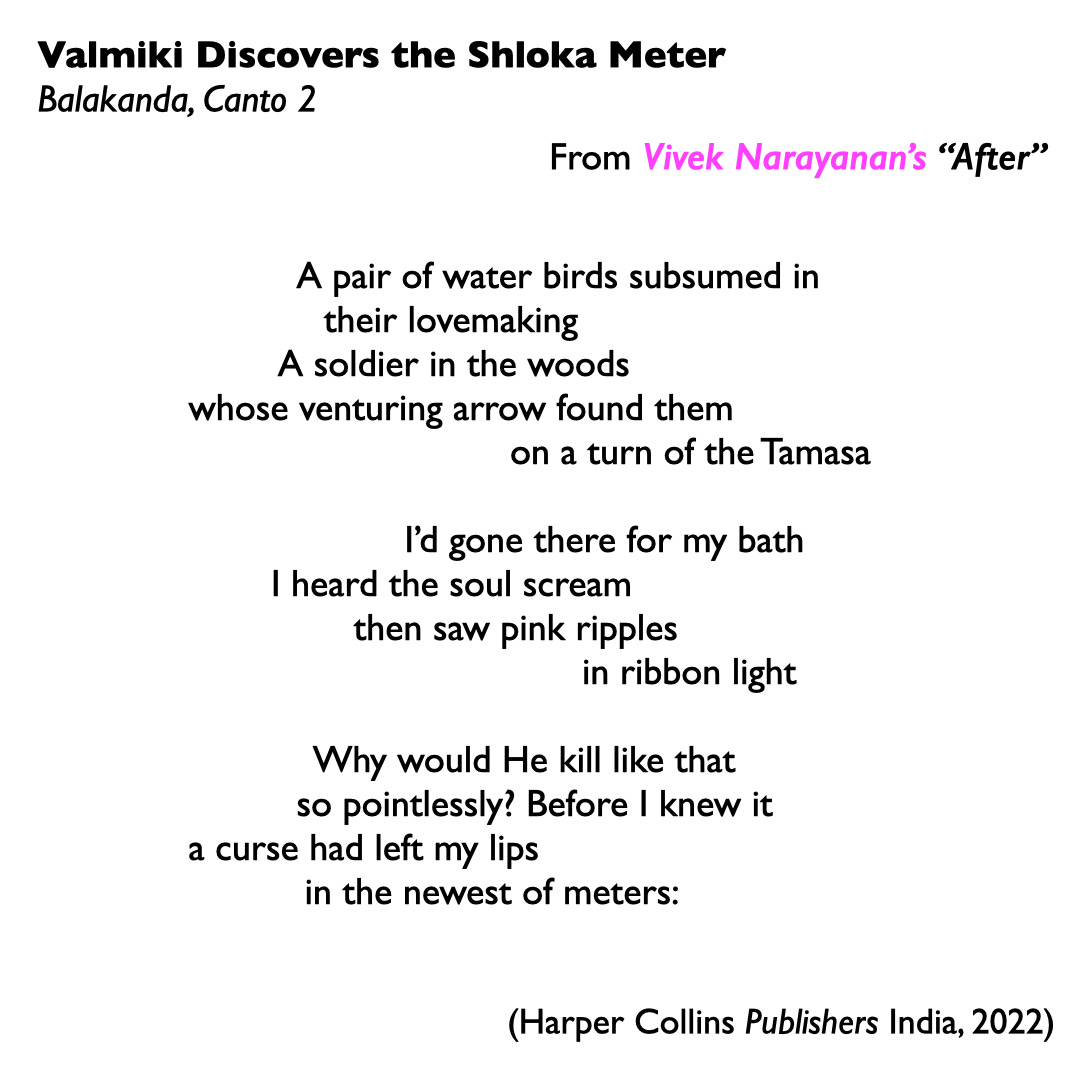

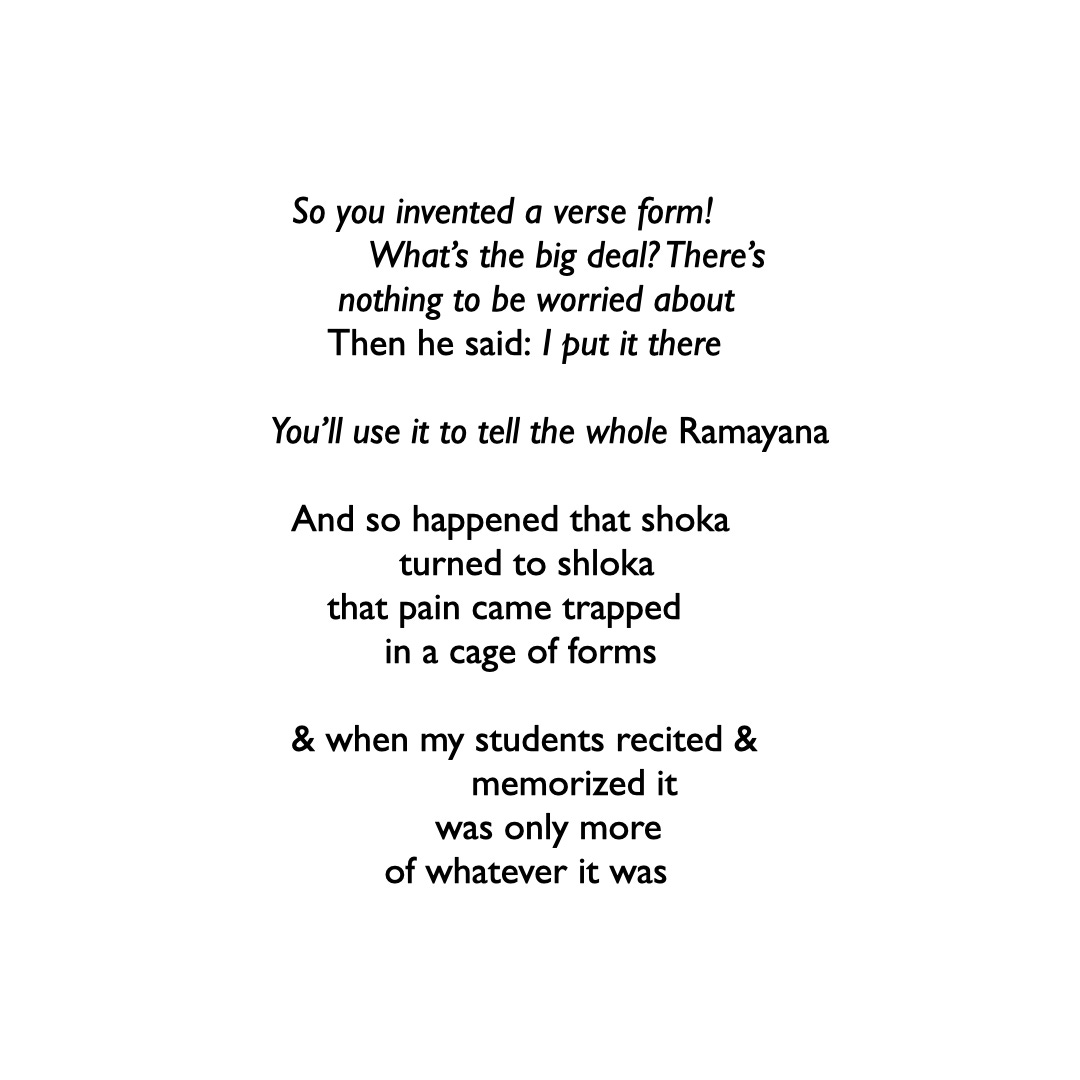

The last poem I share with you today, is from a contemporary work of searing vision, aptly titled after. I share below a poem from the beginning of the modern epic (‘inspired’ by Valmiki’s Ramayana). I place this layered work alongside episodic assemblages such as Kartika Nair’s ‘Until the Lions’ or Sharanya Manivannan’s ‘The Altar of the Only World’ (works by anglophone Indian poets that are consciously political, ‘rewiring’ myth, while attempting to find new languages of expression through formal inventiveness).

The poem describes an auteurial moment of wonder - Valmiki Discovering the Shloka Meter. How did I do it?

I find it difficult to speak about the Ramayana and its retellings without tipping a hat to A. K. Ramanujan’s imagination of the palimpsest that is this epic, and how even within the many versions of the story, there is a seed of reflexivity and multiplicity. We are all acquainted, of course, with his essay (that threatened the ruling dispensation so much that they removed it from English Literature Syllabi across the country) Three Hundred Ramayanas. I’d also like to invoke his contemplation on the notion of translation as being something other than a linear journey from “source” language to “target” lamguage. As Ramanujan would have it, Narayanan, as a kind of translator (Note: he has ‘reanimate(d)’ the epic text, also with an eye on the Sanskrit ‘source’) is another cultural actor, swimming against the river of verse. He is not writing afresh, but recasting the present, the past, and the mythic, in the colours of a language that is at once liberating and contemporary.

Narayanan realises that precious mystery about creation - it is the miraculous surge of emotion that finds new language. It is feeling that affects the corporeal entity giving birth to art: And so happened that shoka/ turned to shloka/ that pain came trapped/ in a cage of forms.

This is the view of the sacred that I wish to leave you with.

The poem can never die, because it never lived. The poem sits in the forest of the real waiting to be found. It sits outside language, dons the syntax of the known and walks into the page, already old. It dies the moment it is read, only to be born again in the mind of the reader. How sweet, this mortality!

How free, this soaring!

I hope you are doing well, and this winter is kind. If you like what you read, do consider ‘buying me a coffee’.

—

Note: Those, not in India, who’d like to support the work I do at Poetly, write to me - poetly@pm.me. (Apologies, I will figure out international payments soon)

If you wanna share this post…