While talking about the translation of classical Tamil poetry, specifically Sangam poetry, A. K. Ramanujan shares a take on the negotiation of language that propels the translator as another actor in the palimpsest of meaning that unfolds across cultures and language:

The translation must not only represent, but re-present, the original. One walks a tightrope between the To-language and the From-language, in a double loyalty. A translator is an 'artist on oath'. Sometimes one may succeed only in re-presenting a poem, not in closely representing it. At such times one draws consolation from parables like the following. A Chinese emperor ordered a tunnel to be bored through a great mountain. The engineers decided that the best and quickest way to do it would be to begin work on both sides of the mountain, after precise measurements. If the measurements were precise enough, the two tunnels would meet in the middle, making a single one. 'But what happens if they don't meet?' asked the emperor. The counsellors, in their wisdom, answered, 'If they don't meet, we will have two tunnels instead of one.' So too, if the representation in another language is not close enough, but still succeeds in 'carrying' the poem in some sense, we will have two poems instead of one.

From his essay, On Translating a Tamil Poem

This delightful little tale about the artisanal project of translation, allows for a broadening of the arena of exploration, for some permission. I particularly like his recasting of the role of the translator as the “artist on oath”. Poets are forever creating tunnels through mountains of time and space. New imaginations of realities are realised in the traversing of these tunnels. Ramanujan’s translations of akam poetry from the Sangam period - “Akam means ‘that which is inside’ or ‘the inner world’ and is, effectively, love poetry (as opposed to puram or ‘outside’)” - could be read within this frame.

In their introduction to The Rapids of a Great River, that features some of these love poems, Lakshmi Holmström, Subashree Krishnaswamy and K. Srilata outline the distinct landscapes that form a backdrop for these poetic forays:

“The idealized landscapes in which akam poetry, in particular, is based, is central to the design of the poems. There are five such landscapes in akam proper: kurinci or hillside, marutam or cultivated land, mullai or forest, neytal or seashore, and palai or wasteland. Each landscape is named after a flower native to it. Not only is each landscape associated with a season and time of day, but also with specific gods, animals, birds, trees and so on. Most importantly, each landscape is associated with an aspect of love: kurinci with lovers’ union, marutam with the lover’s unfaithfulness; mullai with patient and hopeful waiting, neytal with anxious, uneasy waiting, and palai with separation and hardship. There are two further aspects of love, perunthinai or mismatched, and kaikilai or unrequited, which are at the edges of the akam frame; no particular landscapes are assigned to them.”

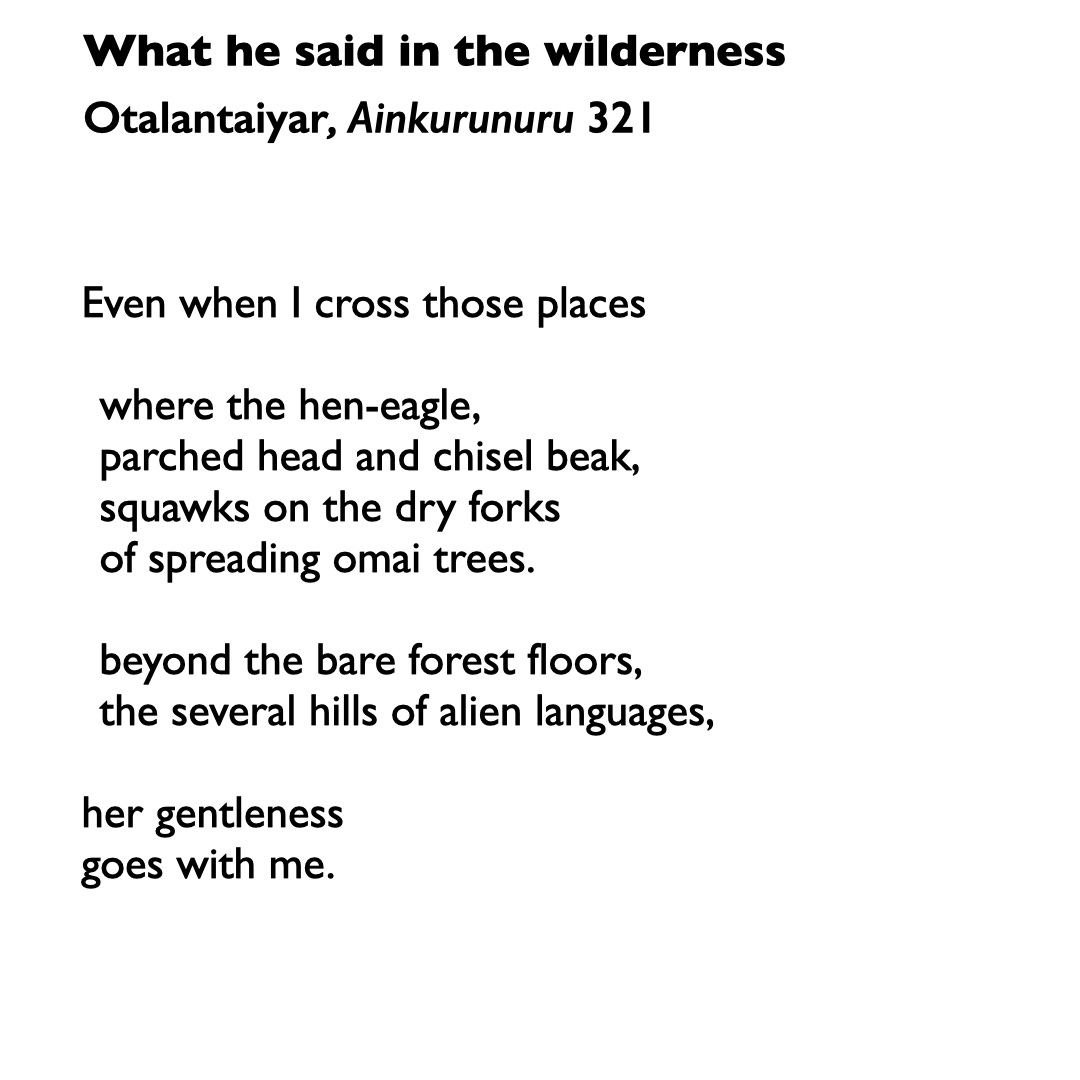

The poems come alive against this backdrop, and we are transported to affective movements that extend across the outer and inner world of the speakers of these poems. The conversational format encircles the matrix of relationships and tonalities, and we are swept with vectors of feeling that forge the setpieces of the various aspects of love. Take for example this poem, that rests very much in the terrain of palai:

How words catch fire, in the last two lines. How the sudden blaze of feeling leaps from the physical landscape to resurface as longing in the lover’s remembrance. The poem moves through the roving vision of the persona’s journey, and we go along with him surveying the landscape, tasting its varied hues. The volta of ‘her gentleness..’ is waiting in the wings, and the sudden relocation of the poetic space, enhances the distance both metaphorically and physically. I feel the jolt, that is not forceful, but, nevertheless conveys the isolation of the lover in the wilderness, whose mind is both present and absent.

The poet recruits the landscape in his musings, his passionate entreaties. This is how it is, when the world slips into the mesh of love - there is no difference between space and emotion, afternoon and evening, as in this Mullai poem.

Ah! This waiting. It reminds me of a line from a dhrupad bandish about the separation of lovers - tum bin kaise fagun maas -and the open vowelled ‘faaaaag-’ curls with meend, a receptacle for the lover’s intezaar, for her longing.

In one of his definitions of ‘waiting’ in his dictionary of love, Lover’s Discourse, Barthes charts the contours of this waiting, and how it expands out of the very scope of that moment:

I am waiting for an arrival, a return, a promised sign. This can be futile, or immensely pathetic: in Erwartung (Waiting), a woman waits for her lover, at night, in the forest; I am waiting for no more than a telephone call, but the anxiety is the same. Everything is solemn: I have no sense of proportions.

When the lover utters - ‘even dawn… is evening, to one who has no one’, I feel this disorientation of a person anxious with waiting, sighing like a coconut frond in a stormy night, like someone who has no sense of proportions.

You could also read my favourite poem from this mix, that I have shared on Poetly before - ‘red earth and pouring rain’

If the poetry and the commentary resonate with you, do consider ‘buying me a coffee’.

(Matlab, if you can’t, that’s also fine, obviously. This will always be a free newsletter)

—

Note: Those, not in India, who’d like to support the work I do at Poetly, do write to me - poetly@pm.me. (Apologies, I will figure out international payments soon)

If you wanna share this post with a loved one…

Thanks for reading Poetly! Do subscribe if you are not reading this in your inbox. Cheers!