I have been gone from your inbox a little longer than usual. My apologies. A few days ago, I burnt my fingers while deep frying pakwans. I was making dal pakwan, a favourite Sindhi dish, for my friends, and a moment of inattention resulted in hot oil splashing on the fingers of my right hand. It’s been a bit foggy since then. Not to worry, though, I feel like I will have the full use of both my hands again very soon.

I took this as a message from the universe to slow down and take a break. The thing is, Poetly is not like other ‘work’, and not writing here leaves me feeling guilty as if I’ve not been keeping in touch with a dear friend. I realise, as I write this, that this space has always been one of correspondence, more than critical distance. I write, here, with some recklessness, allowing myself to wreak language with things that demand attention. When I share them with you, it is the urgency of epiphany that courses through the veins of these letters. I am unable to write about poetry with studied distance, the way some academic commentators do, and I envy them the objectivity that affords them a breadth of engagement that I forgo with this kind of erratic cross-sectional gaze. Some of you might not agree with this approach - I beat myself up for it too, sometimes. But I have come to accept this as something of an occupational hazard, and the record of a constant vacillation between contrasting identities that people the poetic landscape. It returns me to a familiar introspection that is existential in nature, but also contemporaneous in that it suggests moral accountability: What does the poet do?

A poet should learn with his eyes

the forms of leaves

he should know how to make

people laugh when they are together

he should get to see

what they are really like

he should know about oceans and mountains

in themselves

and the sun and the moon and the stars

his mind should enter into the seasons

he should go among many people

in many places

and learn their languages

- Kshemendra, Kavikanthabharana

verses 10-11 (12th Century) translated from Sanskrit by W. S. Mervin and J. Mousaieff-Mason

Ignoring, for the moment, Kshemendra’s insistence on the male pronoun (as a marker of social conditioning), I find here an interesting idealistic vision that propels the poet as a figure of alertness that is not shrouded in elite industry, but rather, the convivial buzz of community, and the natural world. It imagines a quest that goes into the very essence of things, opening up the space for cultural exchange and learning. This vision sees knowledge as drawn from observation tempered with a sensitive humour, rooted in the practice of social relationships, and engaging with the living traditions of the time.

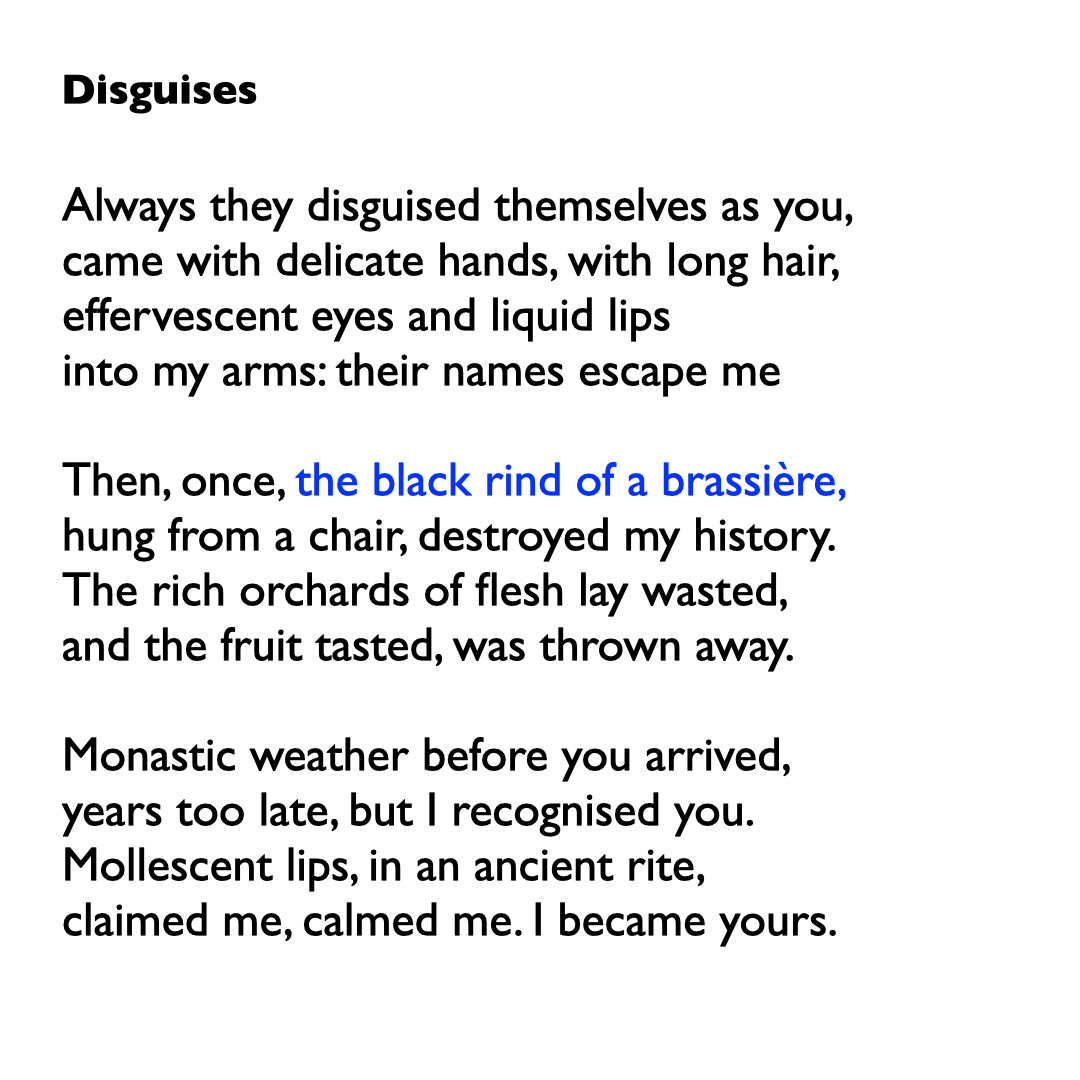

This poem is an epigraph to one of the many anthologies of Modern Indian Poetry that came out in the last century - The Oxford anthology of Modern Indian Poetry, edited by A. K. Ramanujan, and Vinay Dharwadker. The anthology is constituted mostly of translated works that give a fair representation to the multiplicity of literatures that co-exist in this country. The approach uses the label of “Modern Indian Poetry” as a gauze that nurtures the rupture of feeling, and belonging, of native poets writing in their own languages. It is perhaps for this reason that the anthology does not include Dom Moraes. This is somewhat ironic for a poet who is referred to as a “transcultural poet” (Ranjit Hoskote, Introduction to Selected Poems, Penguin). But this is the very crisis of representation that Hoskote speaks about in his introduction - the interpretations of critics who slotted him into the convenient category of ‘postcolonial’, suggesting some aping, some lack in patriotic fervour. He was read as an exile-in-residence of the “new India” that was bandied about with the advent of the modernist impulse in poetry.

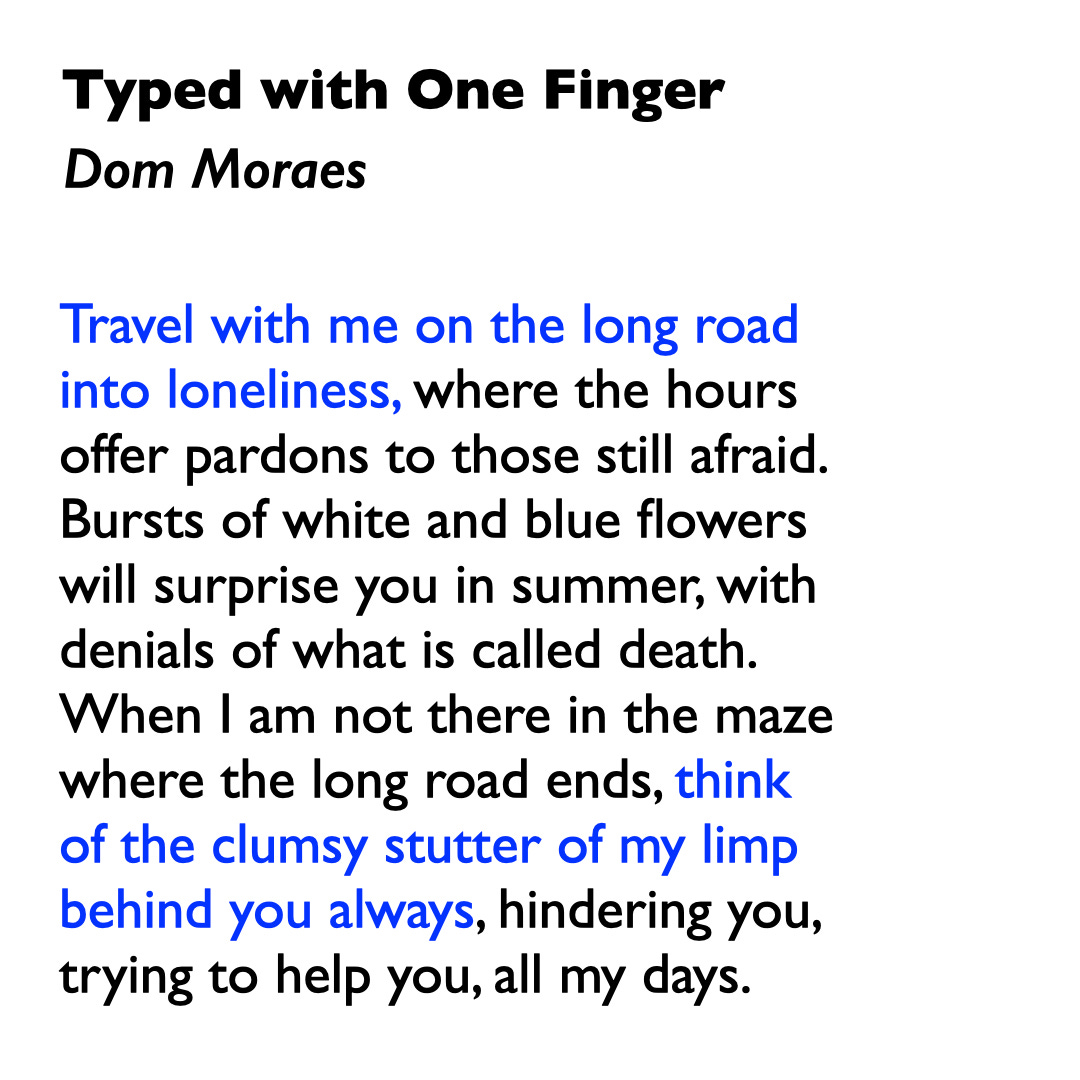

I picked up Dom Moraes’s poems in this one handed hiatus. The eponymous poem from a collection that I had loved, came back to me as mischievous coincidence - Typed with One finger. I have always imagined Moraes as something of a whimsical character - a prodigy who wrote fervent love poems with practised ease (in many of his poems there is a ‘you’ - the pronoun enters, always suddenly, as if those thoughts, not his own, are alive with the shared breath of another). His peculiar way with language, for me, betrayed a constant undercurrent of coming to terms with displacement. He adopted the many cultural spaces he inhabited with flair and intensity, still retaining a deep sense of belonging, even conscientous critique, for the country of his birth. I sensed also, a certain maturity that animated his measured observation, that was very different from the excited experimentation with the idiom, that marked many of his peers.

The poem marks this mature gaze - a poet who saw further, and therefore, was always somewhat out of place in his perceived reality. Hoskote draws special attention to this in his introduction to the Selected Poems - incidentally this wonderful essay helped me recalibrate my lenses while reading Moraes this time, and not simply as a student of literature reading him as one of the “Bombay Poets”: “Moraes’s choices were often misunderstood because they anticipated, sometimes by decades, the contexts in which they could be evaluated and understood.”

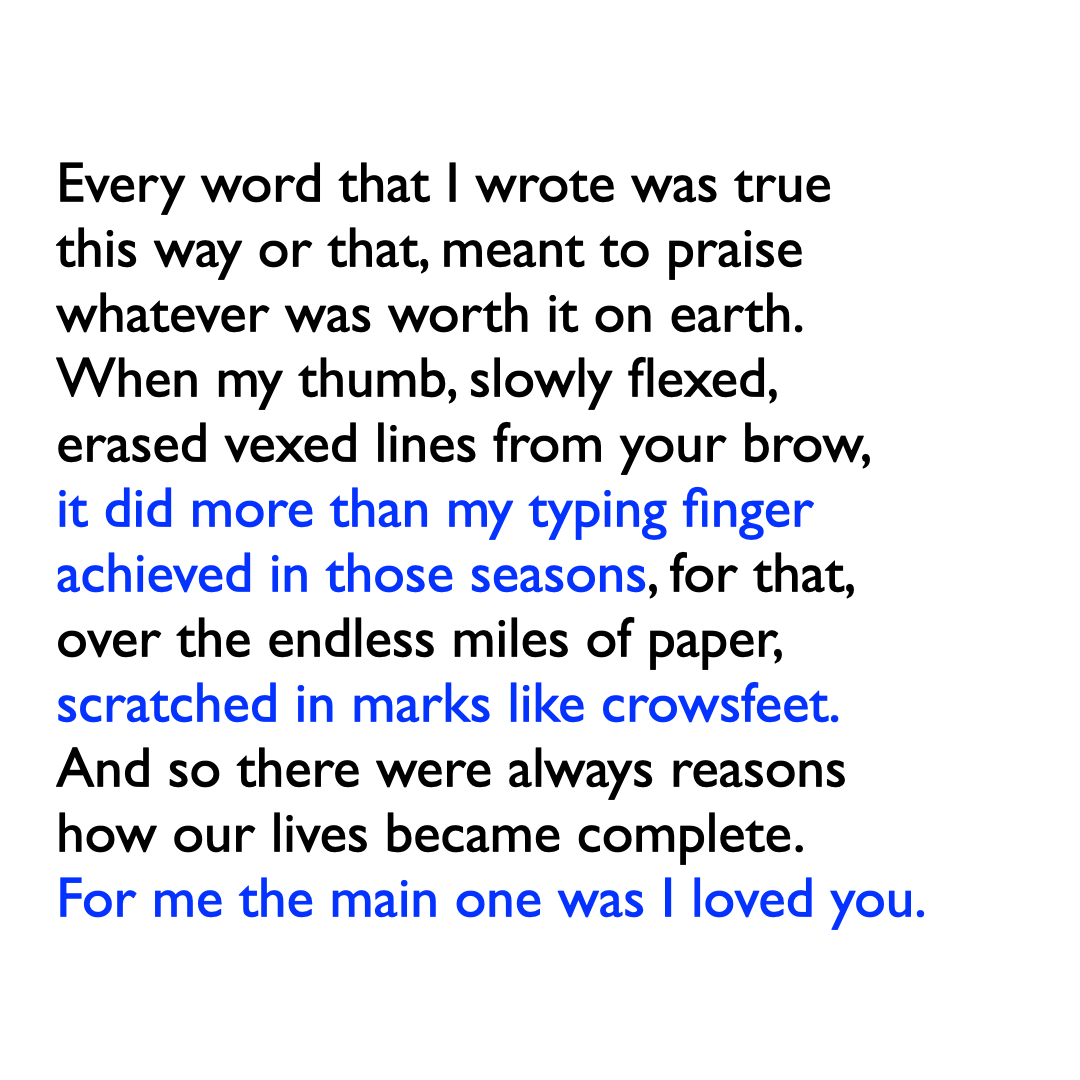

Two images from this poem stayed with me the first time I read the poem - the main one of typing with one finger, and handwriting as ‘scratched in marks like crowsfeet’.

"When I first started to type at the age of eight and nine I wasn't taught to type so I typed with one finger," said Moraes when asked about the significance of his book's title. "Until today, I type with my one finger (on my) computer."

- Dom Moraes's experiences 'Typed With One Finger'

Apart from the mature poet employing this metaphor to talk critically about self-definition through writing, his childhood, and a shifting of gaze, there is the sudden vulnerability of the lover whose pen now speaks through experience, and a radical acceptance of darkness. This is lightened by the tenderness of his plea for memory, and his almost ‘sentimental’ last line invoking a timeless passion. This doesn’t lessen the poem for me in any way, rather it suggests a voice that is entrenched in the habit of the trade of a poet, moving away from itself, and closer to the subject matter. I read this moving away as a deeper honesty, a momentary suspension of self. I especially like the way the perceived cracks are filled with complete transcendence into a space that is defined neither by the self or the other.

Mulling over the lines of this poem as I cut bhindi for sambar using only my left hand and right little finger, it made me think of how the world often wells up in our eyes, briefly distorting it with the shimmer of its moist. Would we be able to see the patterns, whose names we otherwise know only as echoes, if it were not for our brokenness? Would we be able to court slowness as privilege? Is it, perhaps, the inability to complete our subconscious desires, to exercise absolute control on reality, that drives us to see better?

I want to learn from Moraes’s words this unique ability to to use the image as knife, neatly placing the flattened contours of one’s own becoming beside itself.

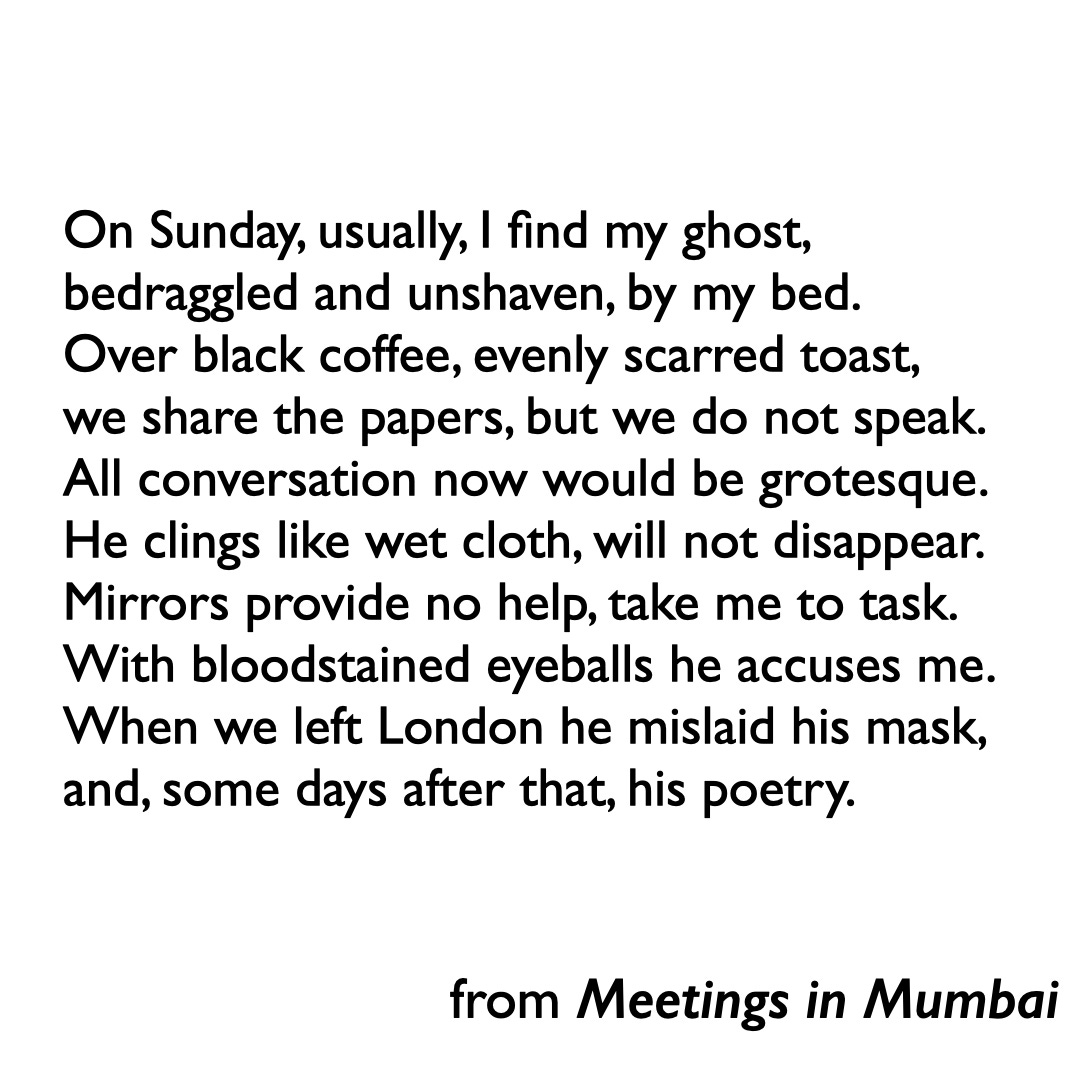

This stanza grows with the nervous assurance of the sheepish smile of curiosity that would be disappointed with anything but the wisdom of a further mystery. It is a kind of dark humour that penetrates the imagery, as if what is broken in reality can be forged into shape with irony. This impulse is evident in a poem about old love from his 2001 collection, In Cinnamon Shade (Before Typed with One Finger)

Not the assured lover of Typed with One Finger this Romeo is wound tight with uncoiled mirth. Once again, though, I feel more, a quiet stiffening of lips, than the brashness of a guffaw.

His writing, even his prose, is replete with a surreal theatre of images tainted with cynical shadows. In a passage from the prologue of a book that he co-authored, Out of God’s Oven, he writes about a Gujrat pockmarked with communal pogroms.

I could go on, but this story has to end. For the last poem, I chose his Landscapes dedicated to (and about) the painter Jehangir Sabavala, and his art. It is structured as a classical Petrarchan sonnet, with an octave and a sestet. I am partial to sonnets, and poems overflowing with this kind of sensual revelry, even in absence. I couldn’t help but share this one, today. I like this poem because it evokes for me, a realm of saudade, shared by two artists. That is all I will say about the poem. Enjoy!

If you like what you read and agar mann hain, ‘buy me a coffee’.

(Matlab, if you can’t, that’s also fine, obviously. This is a free newsletter.)

(If the portal is not working for some reason, please write to me - poetly@pm.me)

Also. Maja aaya tho share this post, nai?

Thankyou for stepping into this shade in the clearing!

Subscribe if you are not reading this in your inbox, and would like to hang out here more often.