everybody is dying, it seems.

the saga began with the eggs, curling around the spectre of the origin question like some incandescent ouroboros. () first came the news of Apparao, ex-serviceman, who would sit below the underpass, at the crossroads, with his crates of desi ande, and the local newspaper, whose laughter tore the morning into shreds, who, fragile staff of a human being, did not know that he would meet with an accident even as the day would start to gather dust. () then we heard about Vilaskar uncle, whose farm was run by a gond couple, who, in search of work far away from the village where they were born (in the forest), had found solace among the goats and the poultry. he, whose booming voice would carry further than the shriek of the chickens. he fell, it seems, just a few days ago. he went without warning, leaving his sons to realise his plans of revitalising the farm - going ‘full desi’, as he put it. () then came Arun Bh’ya from across the street - he died young, did arun bh’ya. his daughter went to the same school my friend did, and they would share each other’s dabbas, he told me. she was a reporter, now. and ev’ry evening, arun bh’ya would saunter into the courtyard, surreptitiously taking small sips from his cup of ginger-infused cha as he made cooing noises to the flowers (his real children) from the side of his mouth. he fell too, in the bathroom, no less - they had even installed one of those cool waist-height metal rods to hold on to… perhaps he spied a shooting star, from the window, and like Humayun, tripped with his eyes trained to the heavens. () Bhato’s mother had the audacity to kick the bucket - in her sleep, mind you - even after they built her a western-style toilet, even after they got her hip replaced. she died on her own terms. () more distant to me, but close to the heart, nevertheless, others have gone, leaving behind only their words - Frederic Jameson, and Keki Daruwalla.

A friend told me that she had met Daruwalla at a literary festival many moons ago, and when she told him that we studied his poems as part of the ‘Indian English Writing’ course at undergrad, he replied, “I’m sorry”.

This story always warms the cockles of my creative heart. like the story of sitting in a tram in 90s Calcutta, only to find a young man, in a crisp, but untucked white shirt, and navy blue corduroys, selling his poetry, typed neatly on foolscap sheets, folded and stapled to make little chapbooks that would fit neatly into the palm of your hand.Written near Kadam Plaza, Borsi, Durg, Chhattisgarh (October 5th 2024)

when i wake up, in the hometown, it feels like generations have plod through the crumbling earth. some nights, with only the moon to give me company, as i lie on the chath of my friend’s home, an owl whistles into the darkness, and precludes the sighs of the dead, who have found silence, at last, and a place to hold their exhaustion. their bodies bulge with the whispering breath of the past, and when their lifeless sacks of flesh hit the earth, the memory of having walked on the soil, with their bare feet, spreads like a thin film on the ground. this is how death seeps into the ordinary. our lives corrode from the inside, and as we decay, the spirit, is (re)born as light. the sharp blaze that shards into vacant eyes, in the heat of conversation, in between the moments that seem important, is nothing but the murmuration of this birth, this dormant heartspring.

i have been thinking about this for some time now. how the everyday is a beautiful mistake, replayed, again and again, across different interfaces. we wake up. clean. eat. work. make love. and sleep. sometimes we become angry.

but we have to learn to hold that anger. we have to guild its stone edifice.

is love the opposite of anger?

(anger is easy

as flight. even a flying fish has scales. but in love there is a soaring, an infidelity - this is what anoints it as freedom. when the bird slips past the ocean, it is secure in its intimacy with the wind.)

certain threads of philosophy dissolve into the contemplation of the nature of death, perhaps, so that they, in pursuit of darkness, and its denial, might chance upon light. our actions are double-voiced, by this awareness, not of being, but having. we possess life. we wrap its heavy kimono around our lithe bodies, and learn to hold the transient permanence of the things we encounter, with gentleness. kindness. this is the way, is it not, of doing things together?

i have been watching the sprawling period piece Shogun, over the last few weeks, whenever i could find the time. even though i completed it a week ago, the series continues to make unbidden entries into my mindscape. i have been listening to the show-runners and the actors speak about their experiences and creative impulses, and about the time and place that they have attempted to re-imagine. i would like to watch it again, and again, to rehearse, how poetry is a part of language, and how language, in its untranslatable duality, becomes a part of action. is this what makes a culture? and unmakes it?

there is a character, who, in her wisdom, holds the many worlds of the show (1600s feudal japan, at the threshold of being ‘discovered’ by the western world) through her navigation of language. she is a translator, whose job description allows her to measure the temperature of a social circumstance, and curate events through her tempering of meaning - how much to reveal, and what to veil. she holds the threads to the slowly unfolding tapestry of power. she is, by far, the most sensitive artist in that imagined space. and i speak, with conviction, of the poetic current that charges every character - not merely as art, but with an intimacy that could be termed ritual, routine.

a line uttered by the translator, Mariko-sama, slipped to the bottom of the mind-pond. i hesitate to call it a stanza. like a sher it has a life of it’s own, but, when slipped into the sequence of utterance, it flowers into emotion. the single line is not really a room, but the wind that whistles through it:

if i could use words

like scattering flowers and falling leaves,

what a bonfire my poems would make.

i have to pause every-time my mind trips over that last flourish. what a bonfire my poems would make. the way in which the conversations unfold in Shogun is a meditation on the nature of translation. the tableaux are enriched with metaphor, and each character dances on multiple planes of meaning, carefully matching words with physical gesture, masking their emotions with carefully choreographed expressions, that falter, occasionally, but only because it is human to feel.

the line, a silken thread of sun-spray that dapples the moments of mourning for an important death in the show, embodies a lived philosophy of duty, above all, even life. Mariko-sama says so much, in that line, about a culture that privileges ritual meaning over the truth of feeling. it comes down to language, and what genres of expression make it ‘social enough’?

think, sans romance, of a cultural world, in which poetry, both veils and reveals emotional thought, through sensation. think of the everyday, of a place where metaphor is intrinsic to the most mundane events. even a simple commercial transaction could hide behind a mural of chipped negotiations, and seasonal flavours.

the form of the haiku, or the imagist manzar, reconciles two different times: a) the seasonal pace of the natural world, that is embodied through the senses- through objects and change b) the simultaneous temporality, the rhythm of the persona’s arc as a maker of poems, and life.

let me attempt a broken translation - of import, not meaning.

if i could use words

if only my speech (expression)

like scattering flowers and falling leaves,

could soar past the shackles of accepted speech to the firmaments of liberated nature

what a bonfire my poems would make

what life could be born from this beautiful death.

when mariko-sama speaks of the bonfire her poems would make, she finds a life beyond the material, and the physical. her words disrupt the measured, mechanical soul of ritual praxis and cultural circumstance. it is (as the season finale is called) ‘a dream of a dream’ that is entrenched in reality through the mundane persistence of her poetic vision - a giant catfish slithering through the ponds of Japan. uttered in the aftermath of an unwarranted death, the poem activates other ‘small deaths’ as life. at once, we are confronted with the schizoid apprehension of the grave ending of a life - the understanding that a breathing, feeling presence has been snapped from the senses, and the fact of the new life(s) that are made possible through this. death lives in the everyday, as the excess of life, not the ending of it.

death has often entered the corridors of this newsletter, of its own accord, and with swag, like a dear friend. take Wislawa Szymborska’s On Death Without Exaggeration. ‘whoever claims that it’s omnipotent/ is himself living proof/ that it’s not’ Wislawa observes with characteristic morbid wit. Death is human, fallible, even clumsy - ‘Death/ always arrives that very moment too late’. elsewhere, Ted Kooser crystallises the visual splendour of death, when he casts attention on a ‘ladybird beetle/ bright as a drop of blood/ on the window’s white sill’. he notices the moment of death, and is struck by how the ‘fear of death/ so attentive to everything living, comes near her’, how... ‘the tiny antennae stop moving’. then there’s Godspeed’s Dead Flag Blues an apocalyptic gem of living sound, and Auden’s As I Walked Out One Evening. When ‘all the clocks in the city’ of Auden’s ‘Bristol Street’ twilight stroll, begin to ‘chime’ and ‘whirr’ a cautioning voice echoes ‘Time watches from the shadow/ and coughs when you would kiss’. The voice is persistent in its soft defiance of forever love (perhaps, different from Andrew Marvell’s To His Coy Mistress) - ‘And the crack in the tea-cup opens/A Lane to the land of the dead’ . My favourite line in the poem, that speaks, again, to how death is punctuation. in the unwinding question that is life: ‘You shall love your crooked neighbour/with your crooked heart’.

we navigate the sidestreets of death, with the persistence of life-affirming deceptions.

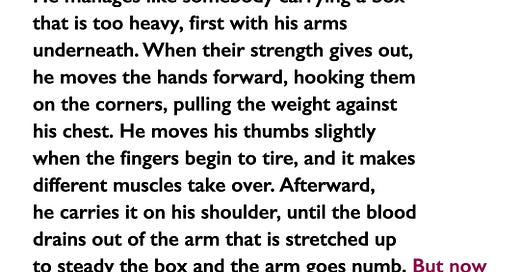

perhaps, one of my favourite pieces of writing that corporealises the grief of passing with a real, unspoken, metaphor is Jack Gilbert’s lament for his lover, Michiko Dead, Longing. They say that most poems of love are about the poet, but this particular variation, speaks with searing passion, about the burden of carrying death in life. taking the reader to the rims of desire, and then, beyond the subjective presence of the persona.

let me reshare it below:

in the beginning of the newsletter commentary to Gilbert’s poem i cite the bard:

“As flies to wanton boys are we to th' gods,

They kill us for their sport.”

- The Duke of Gloucester, King Lear

elsewhere, i remember citing Achilles’s monologue about the great war. i’d reached it, embarrassingly, through the popular Hollywood production of Troy, with Brad Pitt’s delicious lips enunciating each word, even as he humours the spirited Briseis, whose Rose Byrne fights hard, in this version, against the relegation of her character to a minor female persona (as it is in the ‘original screenplay’, Homer’s Illiad).

even two millennia later the Byzantine poet, John Tzetzes (1100-1180) describes her with the same masculine aphasia that leaves out everything but the woman’s physical characteristics, and her alleged ‘moral character’: “"tall and white, her hair was black and curly;/ she had beautiful breasts and cheeks and nose; she was, also, well-behaved;/ her smile was bright, her eyebrows big."

Pitt’s Achilles, however, is given more profound consideration. this is what he has to say about mortality, and the envy of the immortals:

“I'll tell you a secret. Something they don't teach you in your temple. The Gods envy us. They envy us because we're mortal, because any moment might be our last. Everything is more beautiful because we're doomed. You will never be lovelier than you are now. We will never be here again”

i am reminded of Funes the Memorious, but perhaps we must leave Borges for another commentary. let me, instead, state the reason death sticks to my mind, to my fingers even as i write, on this sunwashed October evening, that anticipates the slow demise of fall in dilli.

On Saturday, a great light went out. The Indian state snuffed out a beacon that they had been trying to extinguish for more than a decade. We are familiar with the fascist state’s repeated attempts to quell voices that make them uncomfortable.

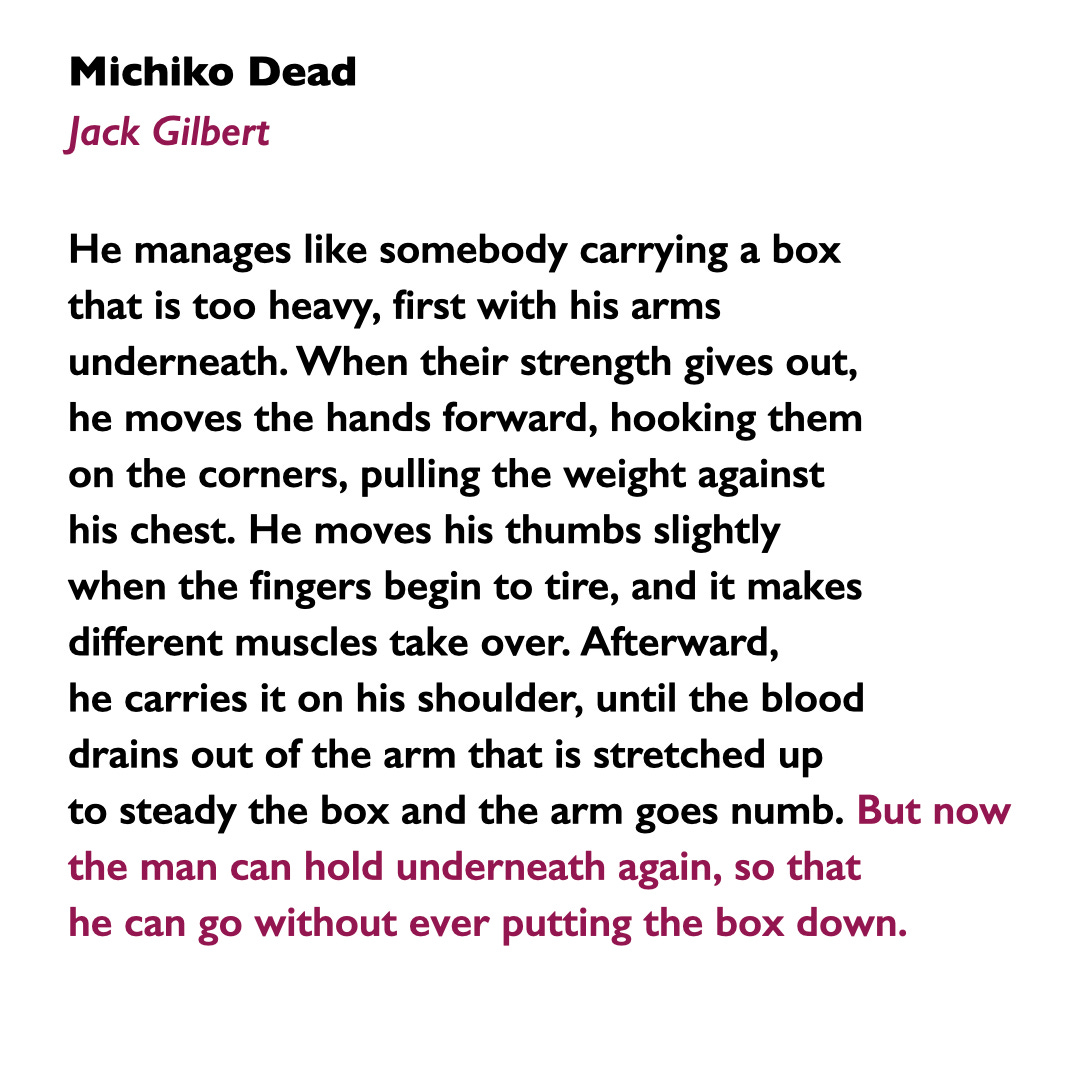

I share below an excerpt from How Long can the Moon be Caged? Voices of Indian Political Prisoners, that details the circumstances of Prof. Saibaba’s detainment, from which he was freed only in March last year. Prof. Saibaba noted that his health condition was grave (even on release) - “It is only by chance that I came out of prison alive”, he said in his first press briefing after being released from Nagpur Central Jail on March 7, 2024. This is how he was incarcerated:

“In May 2014, in what looked like a scene from a movie, a van pulled in front of Delhi University English professor G.N. Saibaba’s car. The police from Gadchiroli, in plain clothes, dragged the driver out, then assaulted, blindfolded and kidnapped Saibaba from the university campus in broad daylight. No warrant was issued and he wasn’t allowed to call his wife or lawyer. His wife, Vasantha, waiting for him to return home for lunch, found out about his abduction from an anonymous phone call. The following day Saibaba was flown out of Delhi and taken to the remote Aheri Police Station on the border between Maharashtra and Chhattisgarh. Here the district magistrate heard the case and sent Saibaba – who contracted polio as a child, is 90 per cent physically disabled and wheelchair-bound – to prison, where he would spend the next 14 months in an anda cell (a small egg-shaped cell in a high security prison) in darkness.

G.N. Saibaba and five others – JNU student Hem Keshavdatta Mishra, journalist Prashant Rahi, members of Adivasi communities Mahesh Tirki, Pandu Narote and Vijay Nan Tirki – were charged with conspiring to ‘wage war against India’. ”

The authors Suchitra Vijayan and Francesca Recchia note that Prof. Saibaba and his family had been hounded by the state long before his arrest. This continued through the decade of his incarceration. The treatment meted out to Prof. Saibaba was subhuman: “I can’t go to the toilet, I can’t take a bath without support, and I lived in jail without any relief for so long.” Prof. Saibaba was wheelchair-bound and over 90% handicapped. I share below a poem whose last few lines have been echoing in my mind since I read the news of his death.

The illustration from the first slide is by Anarya. The poem featured below, and other letters and illustrations, is featured in a collection of Saibaba’s writings, WHY DO YOU FEAR MY WAYS SO MUCH: Poems and Letters from Prison.

Because my words, devoid of meaning and real experience, are taking away from the import of this event, I share the first paragraph of a letter Prof. Saibaba wrote to his students and colleagues:

“Dear friends,

I have lived all my conscious life on the campuses of learning and teaching in search of knowledge, love and freedom. In the course of this search, I learnt that freedom for a few was no freedom. I began to study histories, philosophies and literatures with more eagerness and critical engagement. That led me to look around myself closely. I travelled across and met people living in sub-human conditions. I realised that they never tasted freedom very much like me. I understood that castes and freedom can never co-exist. I began to speak to myself. Then I slowly started to speak to my fellow beings on my journey. I grasped of a great void of silence around me. I saw a society of silence. I dashed myself against the boulders of silence. I brutally wounded myself. A vast majority of the multitudes have never been allowed to break their silence. Centuries of silence solidified in our lives below the high and barren rocks of argumentative India. I desired to break the prison house of silence. I struggled within myself. The rocks were hard to move. I realised that I carried within myself our silent society. It wasn’t an easy journey.”

Rest in Poetry beloved Prof. G. N. Saibaba.

hope you, and your loved, are finding meaning in this tumultous time. do write to poetly@pm.me if you have any questions, queries, or comments. i will write back as soon as I find the space, and the time.

If you like what you read, do consider ‘buying me a coffee’.

I did not know about G.N.Saibaba and the heartbreaking story his life was. Really unfortunate.. Hope he finally found peace... Thank you for introducing him to me.