The journey from “good” or “bad” to “different” is an arduous one. The first point of affinity is often through judgement. We find comradeship in distaste, perhaps, more vehemently, than in shared admiration. I am tempted to think that two poets are assured more in their elitist dismissal of another poet, than in a shared idol, for instance. A young poet-friend once articulated the question: “Are there any big poets, any more?”

Are we not awash in a sea of leaping wavelets of verse, each surge frothing with wonder, and the chutzpah of youth? I see young poets writing everywhere, without the fear of falling, riding the roar of the surf, before they break on another shore. I consider it a privilege to be writing in a time where fame has receded from spectacle to familiarity. Today, the poetry of the everyday, is a deepening. The mundane rewrites itself in myriad voices, and slowly, we change language from within, performing minor pirouettes, embracing small voltas, vaulting with gentle epiphanies. We disdain the romance of the extraordinary, and do not cast achievement as sublime - that is more the stuff of award ceremonies and literature festivals (they have their own place). In the world of publishing as individual practice, when the prismatic self refracts between multiple strands of spectatorship, perhaps one can still discern a rainbow? Maybe there is redemption, even in this miracle fair?

I say this with some hesitation, because it is easy to dismiss/cancel “social media poetry” (for instance) by taking on that elite air of “Nowadays everybody’s an artist/poet”. I do it too. But I take solace in the fact that I encounter more beauty in desire, and curiosity in form, than laziness in execution. The world of poetry reconstitutes in fragments littered across the multiverse. Stray lines, entangled metaphors, or the simple prose of careful sight, wander through the internet waiting for absolution, waiting to turn into a cultural meme. We apprehend the world in fragments, and in moments of sudden attention made real in the shared camaraderie of silent applause. The apocryphal poet of shining armour and galloping amour gives way to a series of discrete signs that exist only as floating signifiers. Every poet is a lesser poet, and the Great Freedom of Thought - that moment of Nirvana, the aha - pollinates language fields with miniscule seeds of sporadic intensity. The moment of truth lives, nowadays, more in dispersal than in singularity.

Vijay Nambisan was introduced to me as a "lesser poet", perhaps because he never quite received the fame and adulation of his contemporaries. Vivek Narayanan, in a tribute to Nambisan writes of the poet who is no more:

"...he had written and published very little over twenty odd years because he had come to the conclusion that “poetry did not matter”. Now it had recently come to him that in fact, “poetry is the only thing that matters”. One could equally suggest that through much of the late 90s and early 2000s it seemed as if there was no viable readership or community for Indian poetry written in English, beyond a couple incestuous pockets; now suddenly it seems to me more sophisticated and full of possibility than ever before."

I had presumed that I shared his famous "Madras Central" on this platform before, but I was mistaken. When I read him today, I was taken by surprise - I was momentarily disoriented by the genius of Nambisan's writing. His intuitive feel for the rhythms and melodies of language produced a rare mix of contemplative languor and profound insight. Phrases return to sentences, but slightly changed, and it is in that subtle transformation, that the real object of his contemplation sits, just out of reach. I'd found him to be interesting before, in the way that a new ‘old’ poet can be interesting, but this time, I tore through the collection, reading each poem several times. Today, more than ever before, I felt a fellowship of vanishing. Narayanan speaks about the shadow of Eliot that is clearly visible (the Prufrockian attitude) in some of Nambisan's early writing. I trace that movement from a youthful cleaving of self to a more mature attitude of literary distance - nurtured by the quiet confidence of experience.

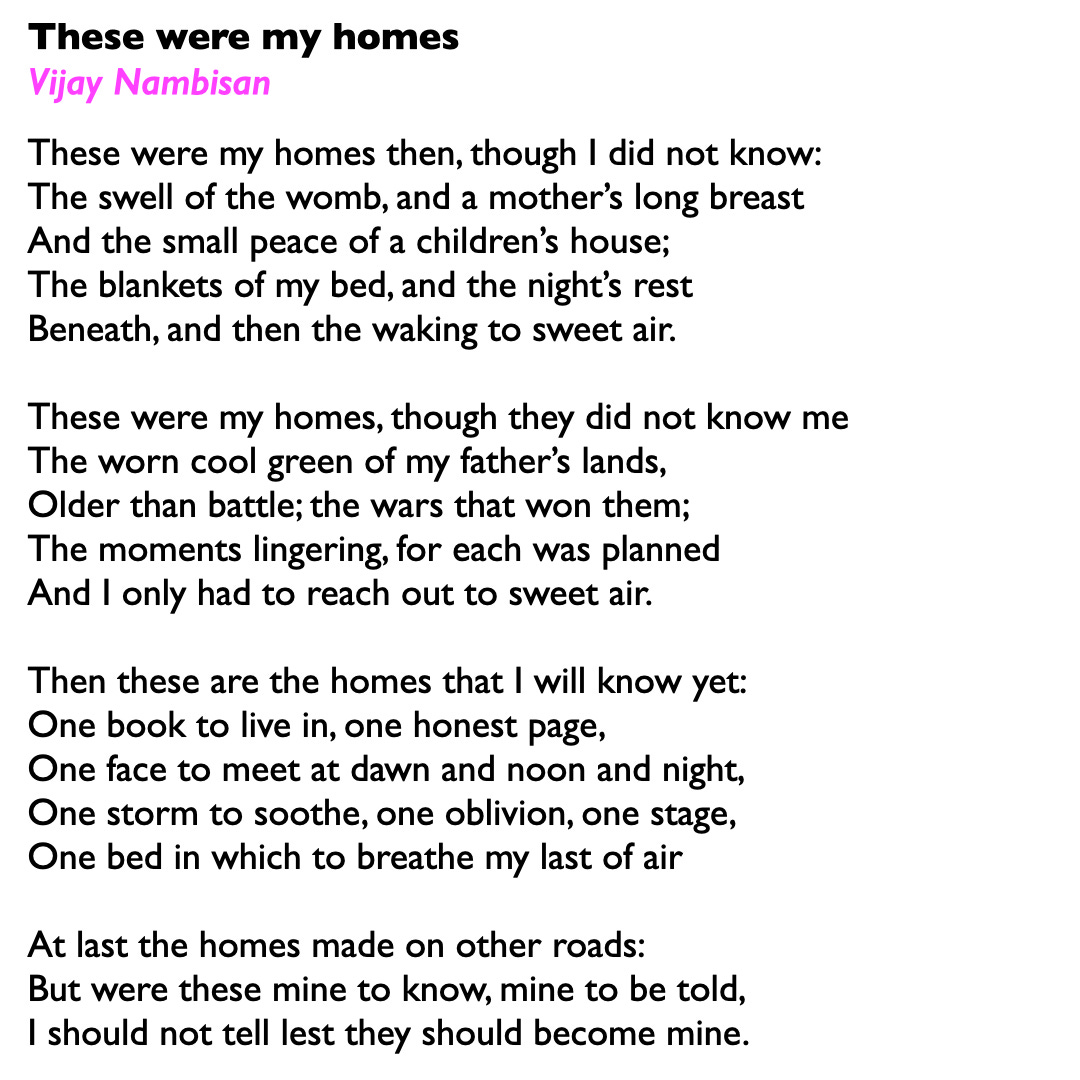

“In the title poem of this volume, "These Were My Homes", Vijay tracks a path from the safe womb to the single "bed in which to breathe my last of air". I can think of few poets who have better traversed that eternal arc.'

- From the Introduction to These Were My Homes, Speaking Tiger, by Rukmini Bhaya Nair

Perhaps this is the most straightforward poem of the collection, by a poet who argued for honesty while writing (One of his authored prose works is called ‘Language as an ethic’). But Nambisan does more than that. Language is a friend to the poet, and he knows what buttons to push. The poet is acutely aware of the sonic possibilities of each word, and his allegiance is to the fragment, not the fully formed idea. I would place Nambisan firmly within the modernists in that he, like the other ‘lesser poets’ I mention in the beginning, changes the terms of conversation from within (even in terms of form). His concern is not a breakdown of the metanarrative - his quest for a centring is evident in the brooding nostalgia of most of his poems. He plays ever so slightly with the frame of the poem, casting it slightly askance, so that you are gently nudged to confront reality anew. Not for him, the expansive turn, or the manic Beat verse. This is why, when I read a phrase like “the small peace of a children’s house”, I can safely say that the poet is aware of the sonic echo of “the small piece of a children’s house”.

With “One honest page” we see again a sense of moral reckoning. I subscribe to this sense of belonging. I could live with a sensibility that embraces presence rather than possession. Even need is articulated in the vanishing of the self. The poet meets the world by sinking into the background of his own poem. His final flourish occurs in a moving away from ownership - “I could not tell lest they should be mine”. The last abode is the self - tentative still, uncertain, and vulnerable.

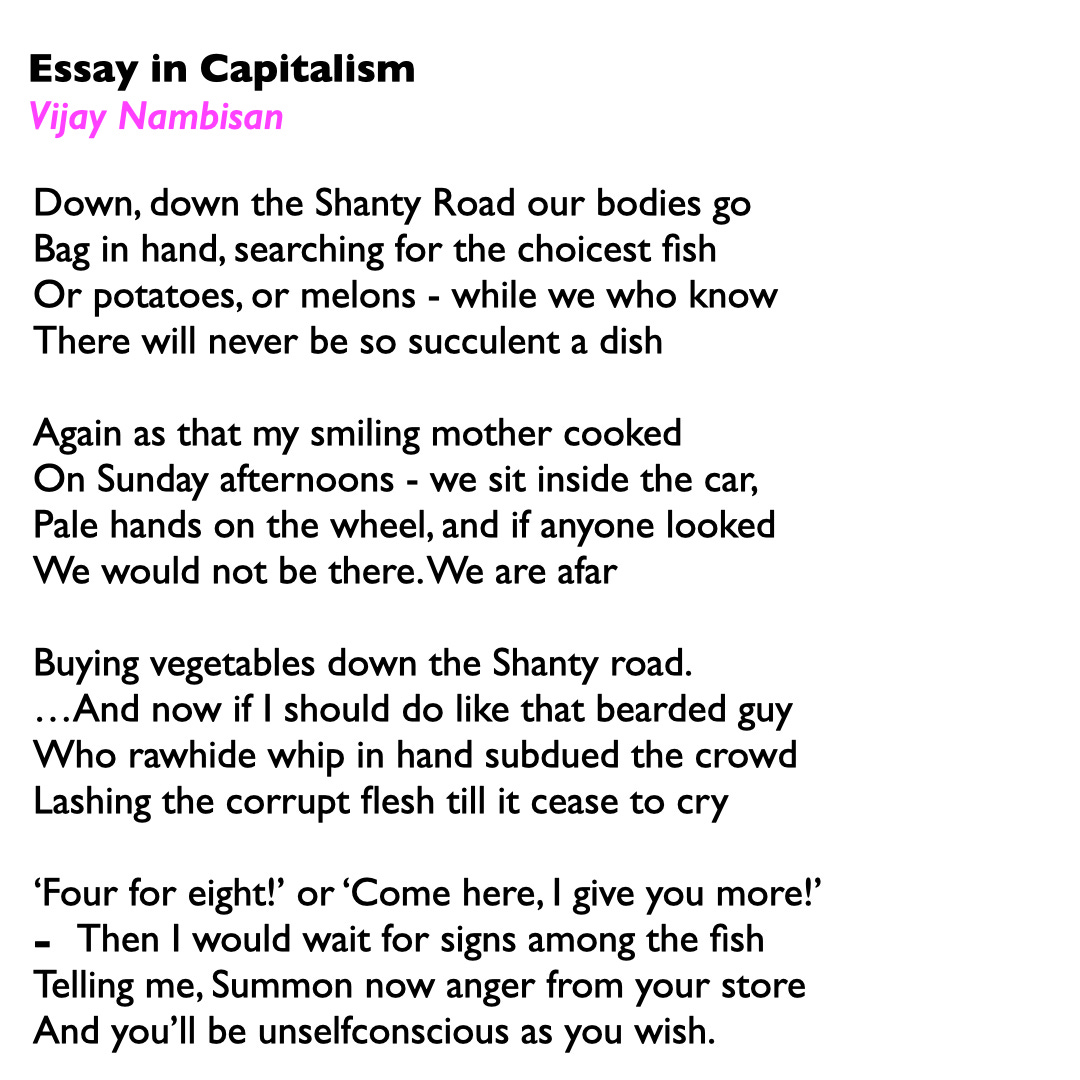

I consider this to be a remarkable example of a ‘story poem’. Nambisan plots the narrative with care - heaping one scene after another, shifting between character, mood and setting almost unnoticeably. Before we know it, he’s painted a complex landscape, smudging the expressions on the faces of various personas, in a hide-and-seek of meaning and affect. The dissociation in the third frame of the cinematic pen - from “We” to “I” - marks another layer. Who is this we? Who is the I? Are these the same person?

I wager that the poet is metaphorical at multiple levels, questioning, even the idea of a singular poetic persona, or a being self. The poem unfolds like an accordion, and each note is a page (one book to live in, one honest page) on which the poet paints the self, the past, the other, the collective, and in the last analysis, society. He ends the poem with “I am that beardless guy who makes the market go”, and in that moment, my heart raced right back to the start line: “An Essay in Capitalism”…

…A good poem suggests the possibility of language in a world saturated with speech.

This is a good poem.

I hope you are doing well, and this winter is kind. If you like what you read, do consider ‘buying me a coffee’.

—

Note: Those, not in India, who’d like to support the work I do at Poetly, write to me - poetly@pm.me. (Apologies, I will figure out international payments soon)

If you wanna share this post…