Long time no see, friend!

Different kinds of work have kept me away from being able to give dedicated time to Poetly. Fragments from this essay have been on my laptop for some time now, and perhaps today is the day to put them together here. Bear with me, dost :)

I have been getting queries regarding the fate of the ‘Meanwhile’ anthology. While I’ve replied to most people individually, let me quickly do an update here, before going further.

Poetly received some breathtaking work, and this project gave me the opportunity to engage with some startlingly original voices that breathe new life into “Bombay city”. The submissions reminded me again of the different ways in which the city is birthed not in its material poesis, but in the shared synchronic arc of collective imagination. I was thrilled to be able to form connections between the submissions and the fragmented but interconnected body of historical work that I see as ‘Bombay City Poetry’. Unfortunately, for various reasons, a physical anthology could not be realised. I have been in touch with the poets.

While some poets have agreed, I am awaiting final permissions for there to be a “critical mass” - enough to do a series of Poetly posts, with citations/commentaries /introduction. I was hoping to curate a physical anthology. Ah well!

I am still excited about this somewhat truncated curation, and I hope to showcase these voices in the newsletter.

The time for a comprehensive contemporary anthology of Bombay poetry with a creative-scholarly introduction that can discursively contextualise and do justice to the writings of young poets writing about the city today, will come, I am sure. But it is not now. This is a lifelong project, and I hope you believe me when I say that I will not abandon it easily :)I thank all the writers, here, again, for their patience, trust, and kindness.

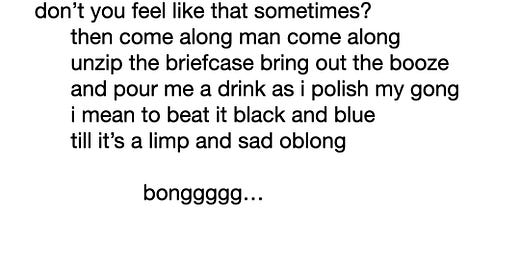

Today’s commentary continues the theme of Bombay city. The first extract (inevitably I return to Arun Kolatkar) begins with a simple but profound articulation. Only after I read these oft-read-in-the-mind-and-recited-out-loud words written on the page here, do I fully grasp the primordial force embedded in them: ‘today i feel i do not belong’.

This poem is from a series of drunk poems - songs - written by Kolatkar. I read this “drunk phase” in Kolatkar’s writing the way I would read Picasso’s Blue Period - with an intermittent aesthetic cohesion that infuses the experiences and visions created therein with some temporal resonance and meaning. While reading Kolatkar is always a dynamic, interactive experience that makes the words leap out of the page, the element of dialogue, sonic rhythm, and everyday speech is more pronounced in these songs. Kolatkar is always speaking intimately to his reader in his descriptions and images, and I must say that this experience is more pronounced in his marathi and “Bambaiyya” poems.

I’ve been revisiting these different songs over the last few months - not as a scholar, but as a poet trying to find meaning and creative thrift in the ideas-in-conversation of another artist. Reading these poems aloud affirms A.K. Mehrotra’s assertions in his introductory essay - Death of a Poet, where he identifies Kolatkar’s musical inspiration (the Blues, and Elvis, for instance) as well as the various attempts to make a “golden disc” - through recordings. It is well known that Kolatkar learned pakhawaj with Arjun Shejwal, and also had a kind of “apprenticeship” with Balwant Bua. The musicality of these poems, and the sonic resonances of the vocabulary suggest an effort to infuse English with the natural chand that is found in Marathi Abhang, Ovi and other forms used by the Bhakti poets. B.S. Mardhekar’s explorations of the Ovi, of course, influenced Kolatkar. I have referred to how his writings illustrated the ways in which traditional forms could be used to give voice to a modernist urban experience in this piece about Bombay, through its poets (Marathi and English).

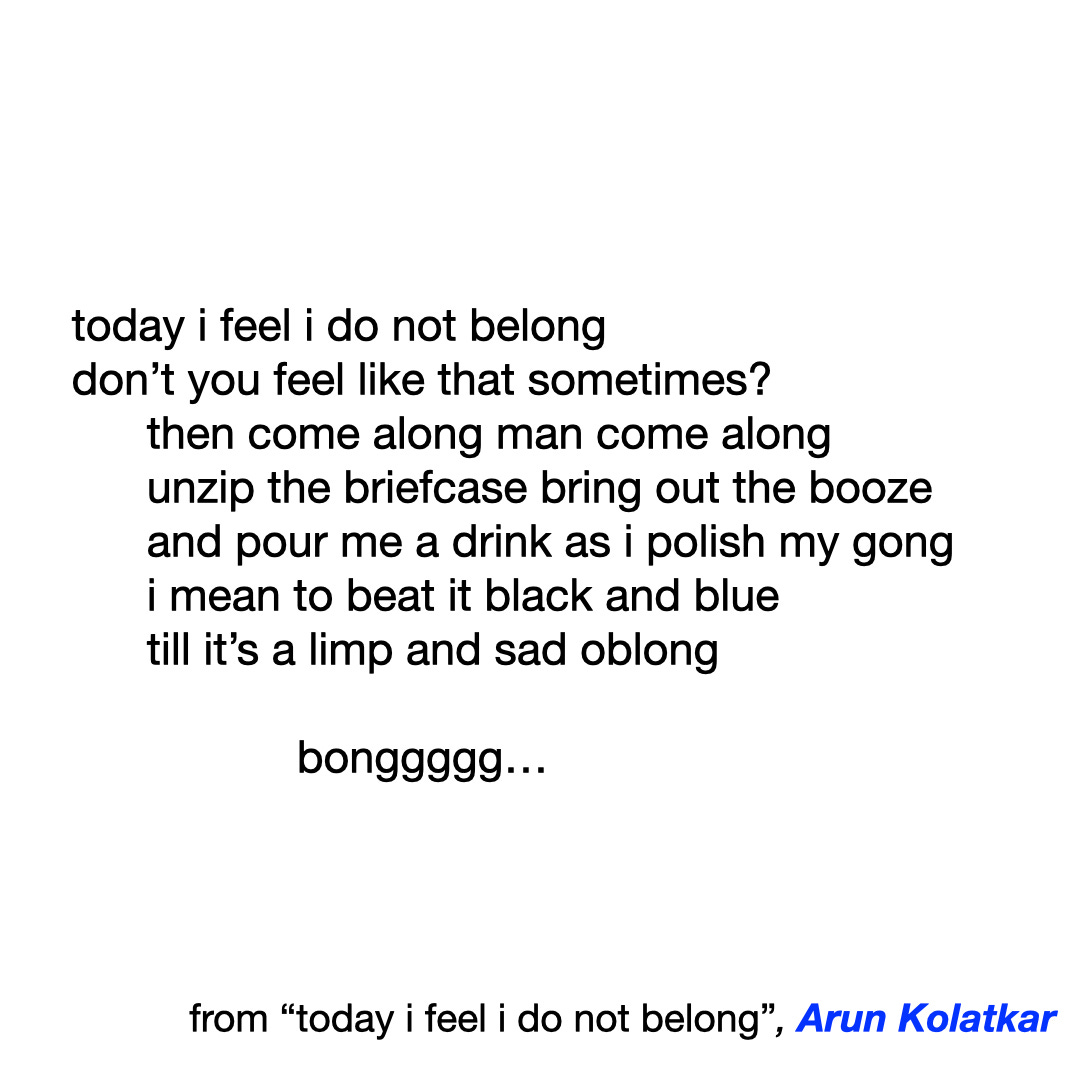

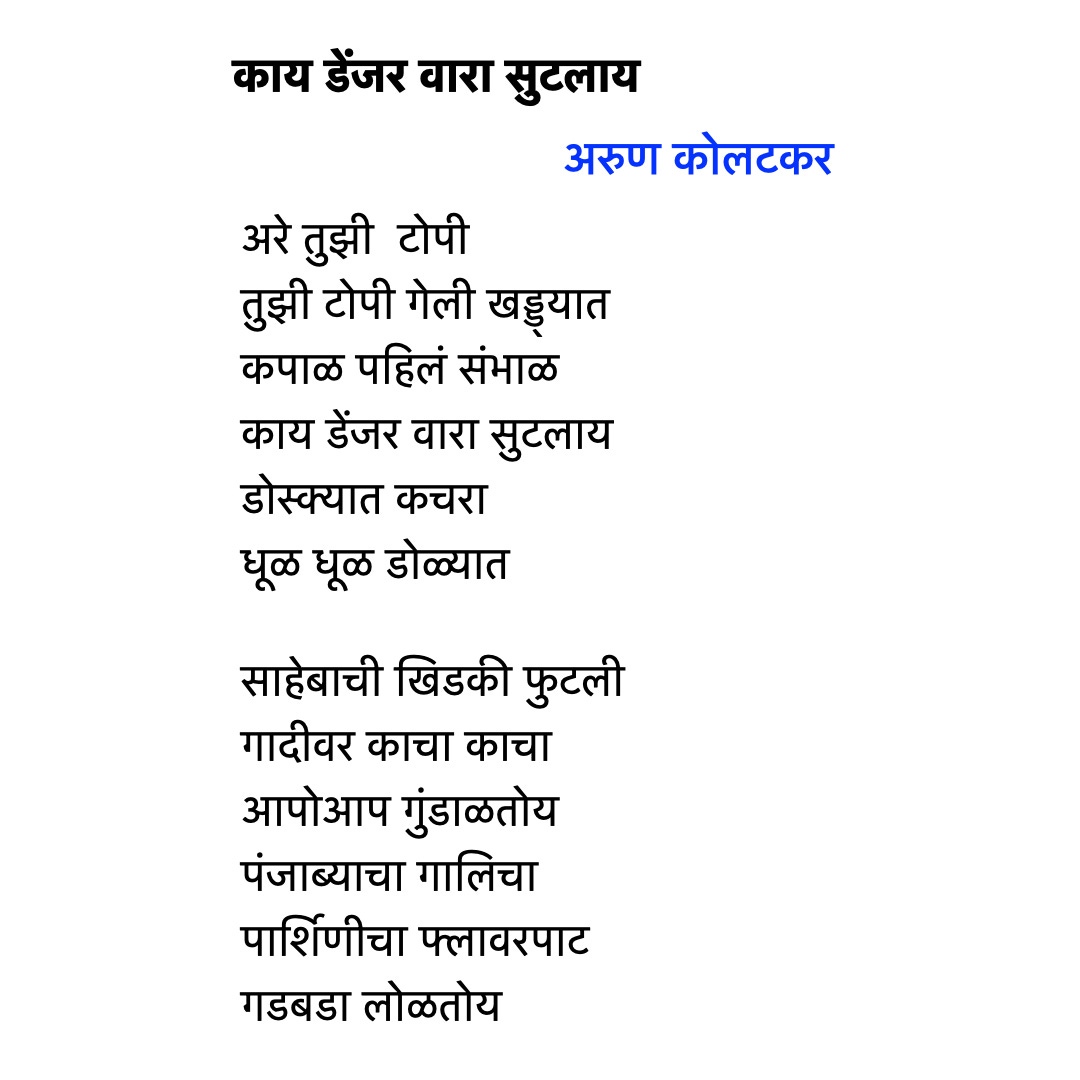

It was in this context that I reached “Kaay Danger Waara Sutlaay” (“What a Danger Wind blows”) some time last year. I read it first as a fun poem in Marathi, and I enjoyed it so much that I immediately attempted a translation. The discovery of the “Marathi Kolatkar” in the last 2-3 years has been a rewarding and deeply pleasurable journey for me. Slowly parsing through his original marathi poems, and finding hidden tributes and callouts to other Marathi poets (and then reading their work) has introduced me to a side of Kolatkar which is vastly different from his English oeuvre. While there are some interconnections, one of the sections in my larger research project attempts to make a contribution to the enormous task of “assimilation” and “annotation” laid out by the literary scholar Rajiv Patke in his assessment of Kolatkar’s engagement with mythology: “The two readerships [English and Marathi] need to join forces in making sense of how and why Kolatkar battled so long with the Indian epics, against the grain of the culture that made him, so that our humanity could rest on a broader footing.”

I find myself revisiting the theme of “myth” and “sacrality” again and again in these interesting times. Don’t you?

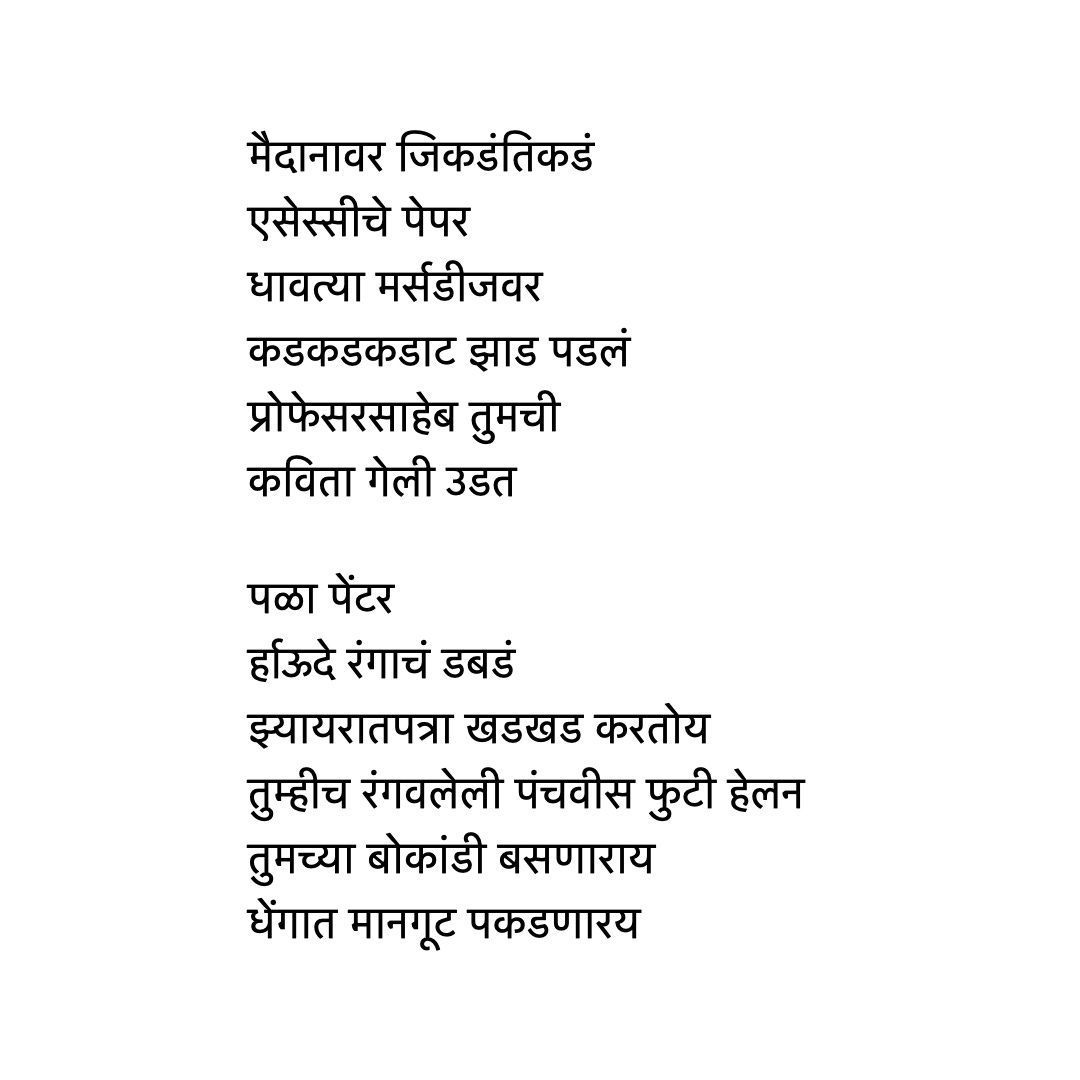

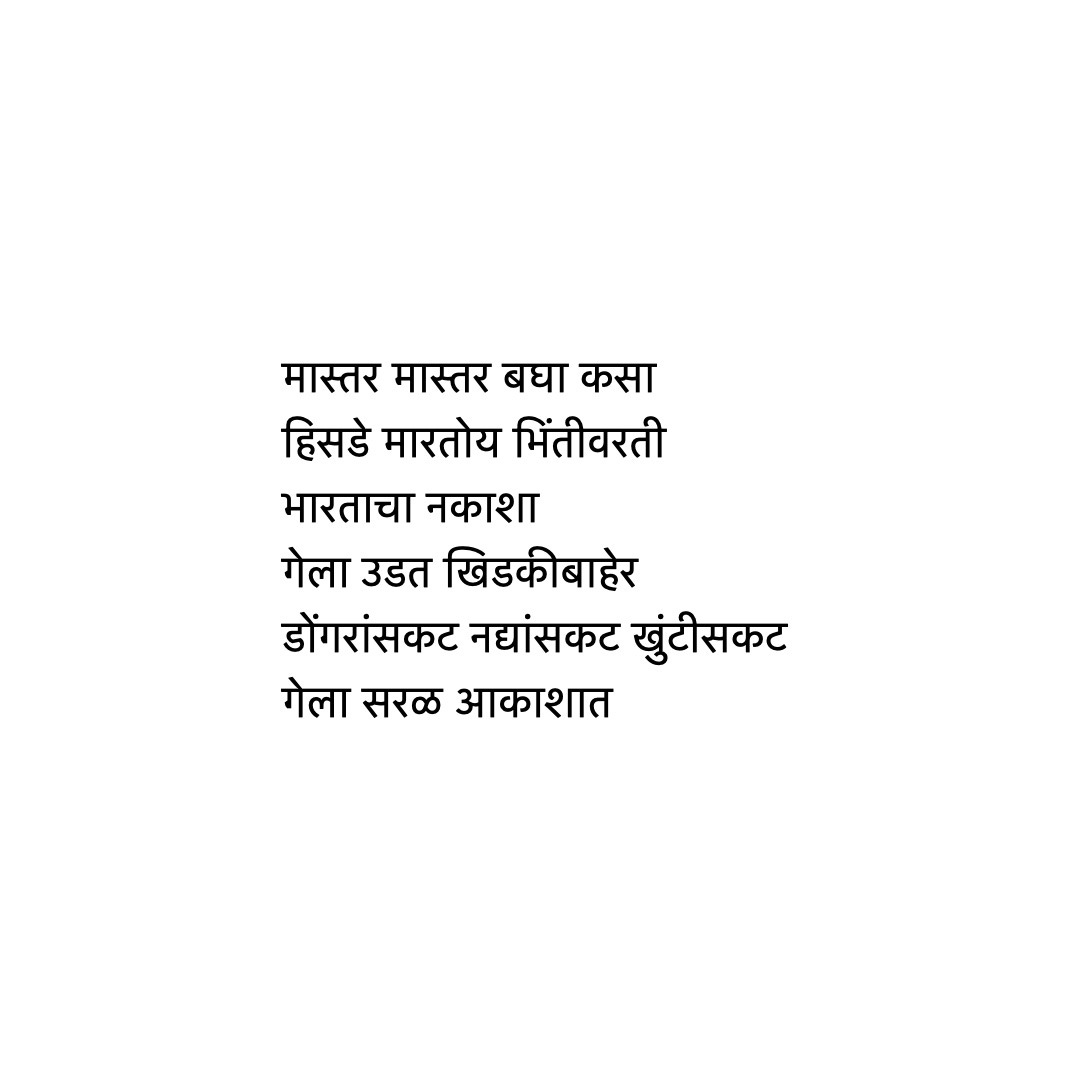

The dubious question of translation is ever present in Kolatkar’s works, and I have found translation to be an excellent method of reading, especially because Kolatkar has written English versions of many of his own Marathi poems. These versions are not “translations” in the conventional sense and they haven’t been written with the intent of faithfully translating the original poems. They might be called cultural translations, but I can say with some certainty that the embellishments and creative rewriting render them as independent poems in their own right. Let us have a look at two versions of the same poem to explore this further. First, the Marathi. Spoiler: Intuitively, I like Kolatkar’s Marathi version more than the English version.

(Note: For those of you who do not speak Marathi, but can read the Devnagri script, I urge you to read the poem aloud simply to listen to the cadences of Kolatkar’s syntax. Read it as if you are reading a conversation. Experience the rhythms of his unique Bombay streetspeak - replete with untranslatable humour and the urban everyday. Ideally, I would loved to have included a vocal rendering here, to help with the marathi pronunciation

Delhi has been seeing the usual summer gusts - the windstorms or aandhi that occur around April-May. Some of these have been particularly lethal - causing material damage; even the death of a few people! I live in a barsaati, and so violent was one of these “danger winds” that it blew off a metal sheet that my landlord constructed in our terrace only a few months ago, along with chairs, an entire section of metal railing and a concrete pillar! Fortunately, nobody was hurt. My flatmate and I saw this damage only on the next morning, and it took away the romance brought on by the sudden change in weather pretty quickly. I shared this poem with friends, on the night of that particularly strong gust, along with my translation. At the time I did not realise that Kolatkar had done an English version of the poem.

I was struck by the presentness of what might sometimes be considered a “light” piece of writing (like his “alphabet” poem, or one of the drunk songs). As it is with all his writing, the reader must read the poems again and again to recognise the allusions (even unintended). There comes a point when the sensitive reader corporeally inhabits the quaint intertextual and subtextual irony of his world, making it their own. (Is there any other way to experience poetry?) This reading is an affective act, and I can only hope to gesture towards it through translation and commentary - We remake each piece of art as we read with attention.

Consider, for example, the allegorical resonance of a “danger wind blowing” amidst the whirlwind of aggressive calls for war.

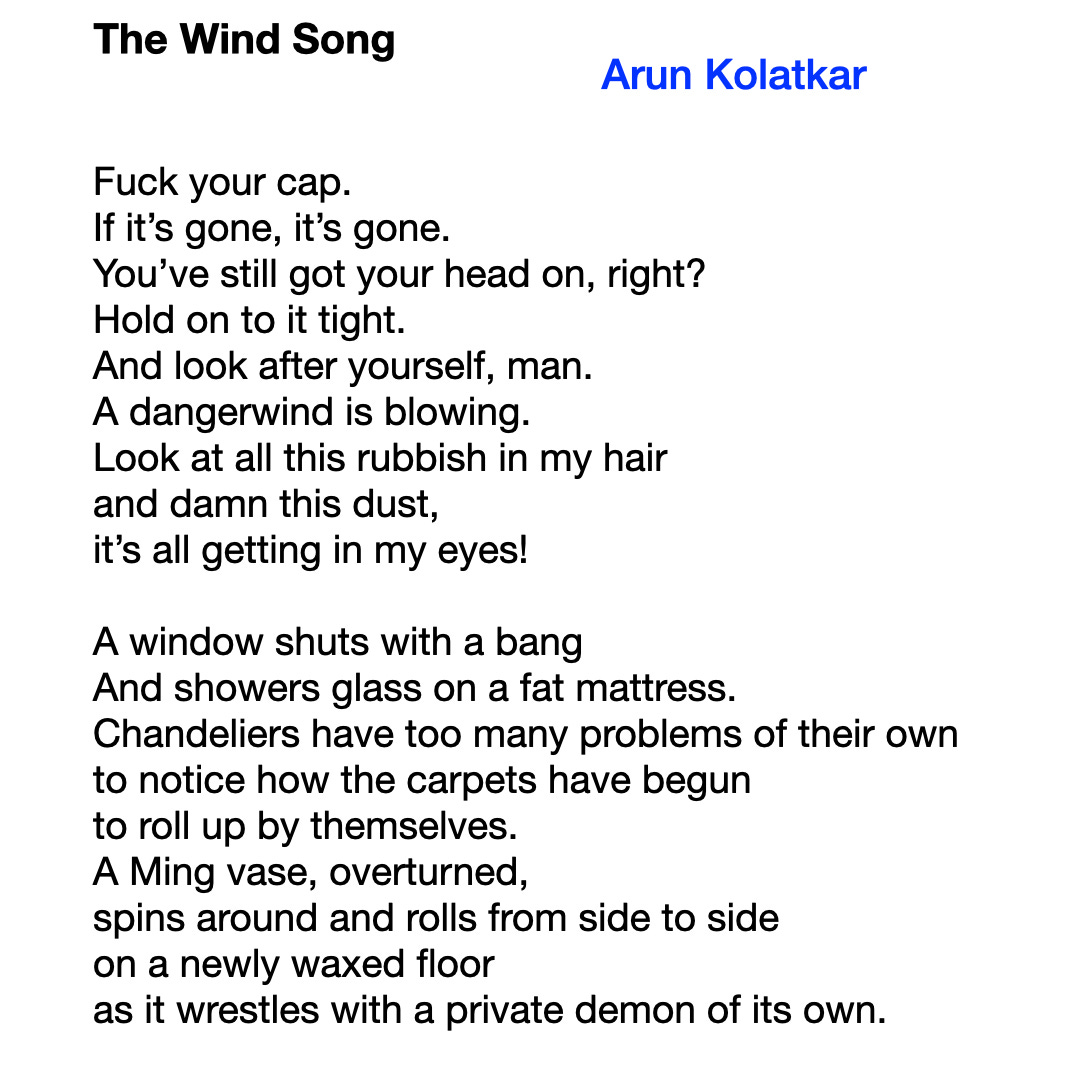

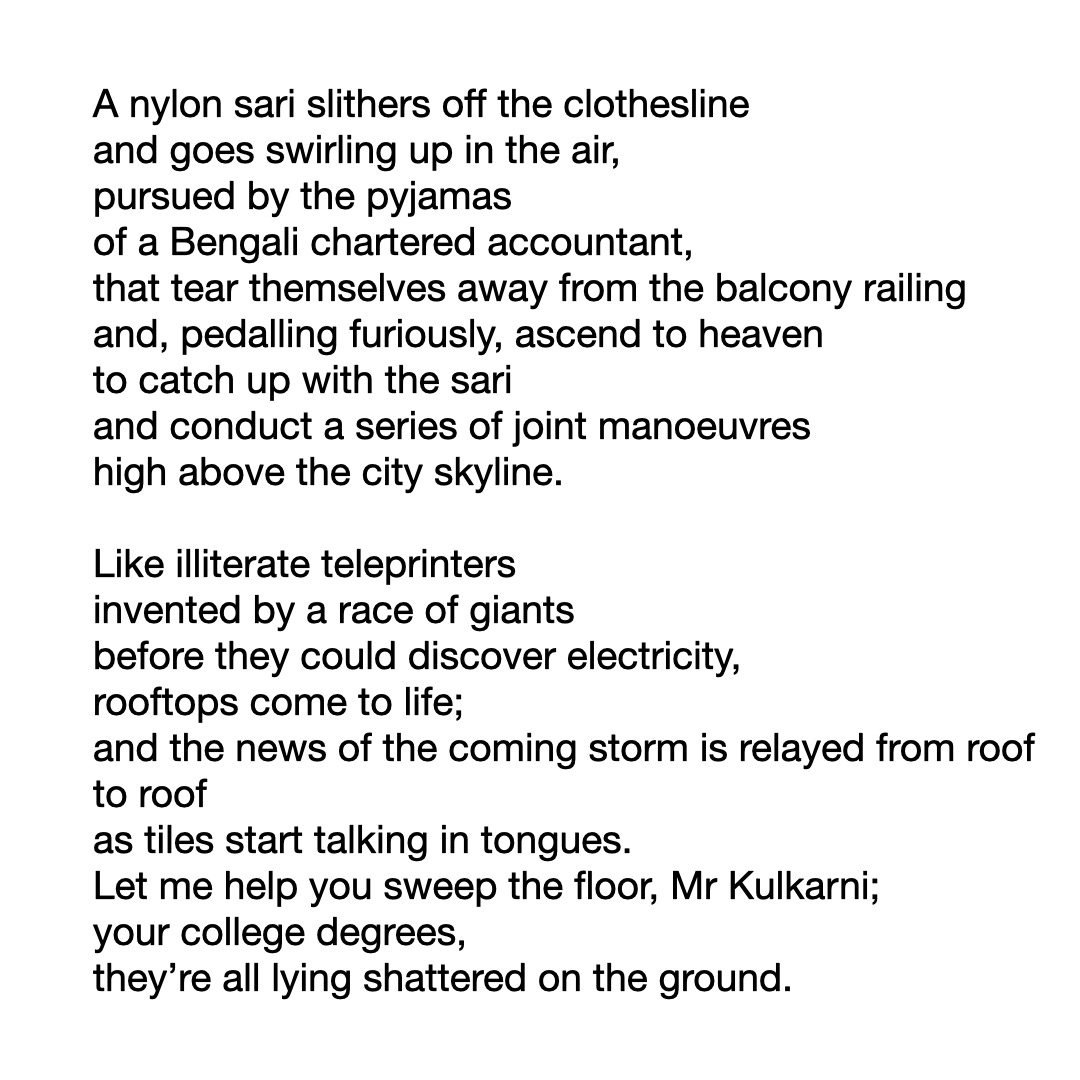

Here is the English version (You will find it in the wonderful A.K. Mehrotra edited Bloodaxe publication of Kolatkar's “Collected Poems in English”):

Masssst… na?

So much mirth in the everyday. In the Marathi version it is the character of “Helen” who is on the billboard. Each stanza is constructed from imagery that is filled with movement. The dangerwind animates the environment, and in each description - each vision - lies the cross-section of a cultural world. Each object lives as a character, with vivid shades that animate the image. The persona’s tone of voice - a booming, filmy commentary - infuses the sensation of movement with emotion through visual description. So magical is this heady blend of subterranean poetics, that I am transported immediately into that swirling animal soup of objects, people, and association. Boxed as we are, in this virtual environment, inhabiting the poem allows me to subconsciously reflect a way of looking, and sensing an interrelated urban ecology.

Enough has been discussed about Kolatkar’s and the other Bombay poets’ “enchantment of the ordinary”, and the vita of “everyday intimacies”. My own writing - even my own perception of the place I call home - has been tremendously influenced by these idioms (what Mehrotra calls an “urban vernacular”). I share a poem that I had written more than ten years ago that echoes this theme. Retrospectively, I might have called this derivative, if not for the fact that I hadn’t read “Kaay Danger Vaara Sutlaay” or “The Wind Song” when I wrote this.

My poem isn’t set in Bombay. This is the original, unedited draft.

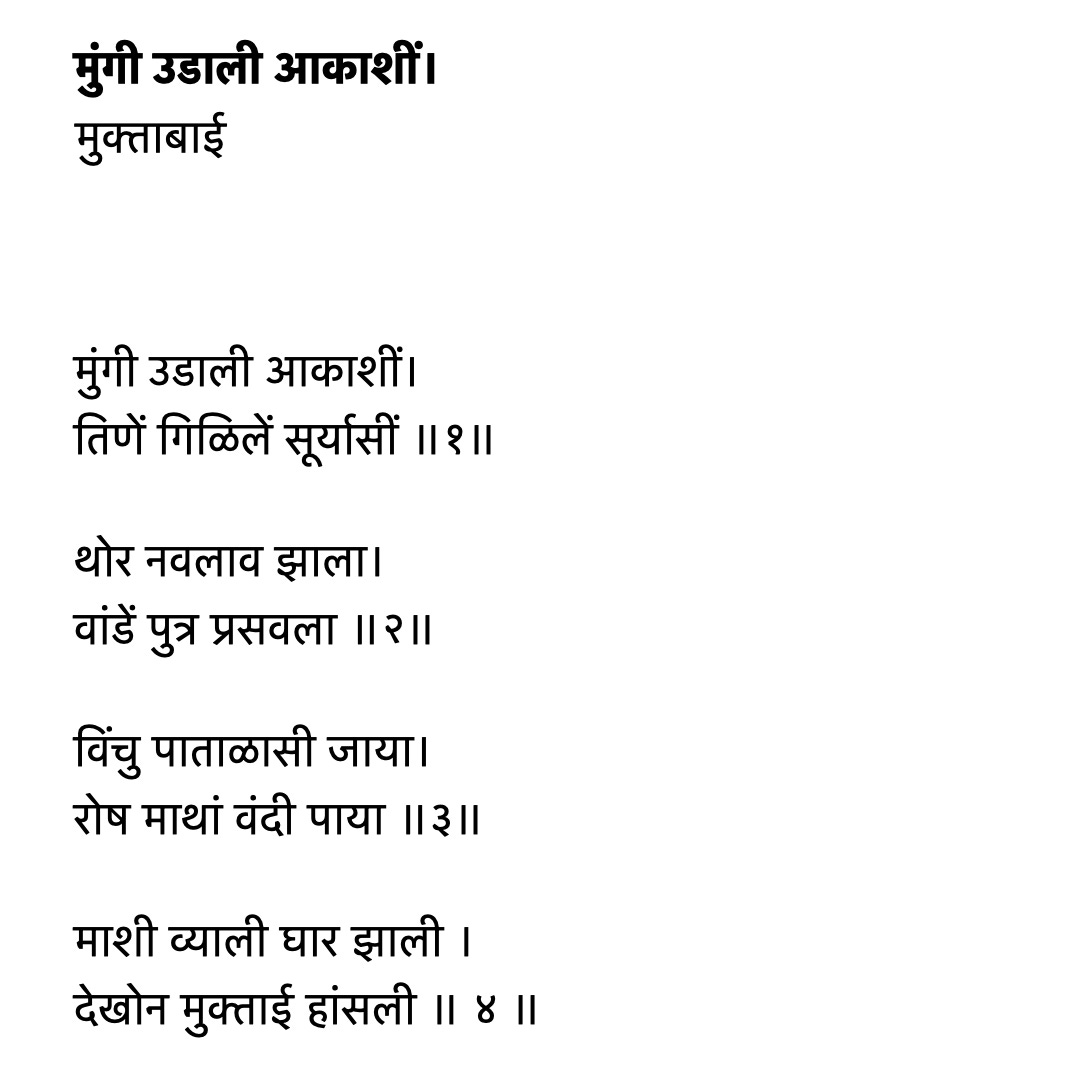

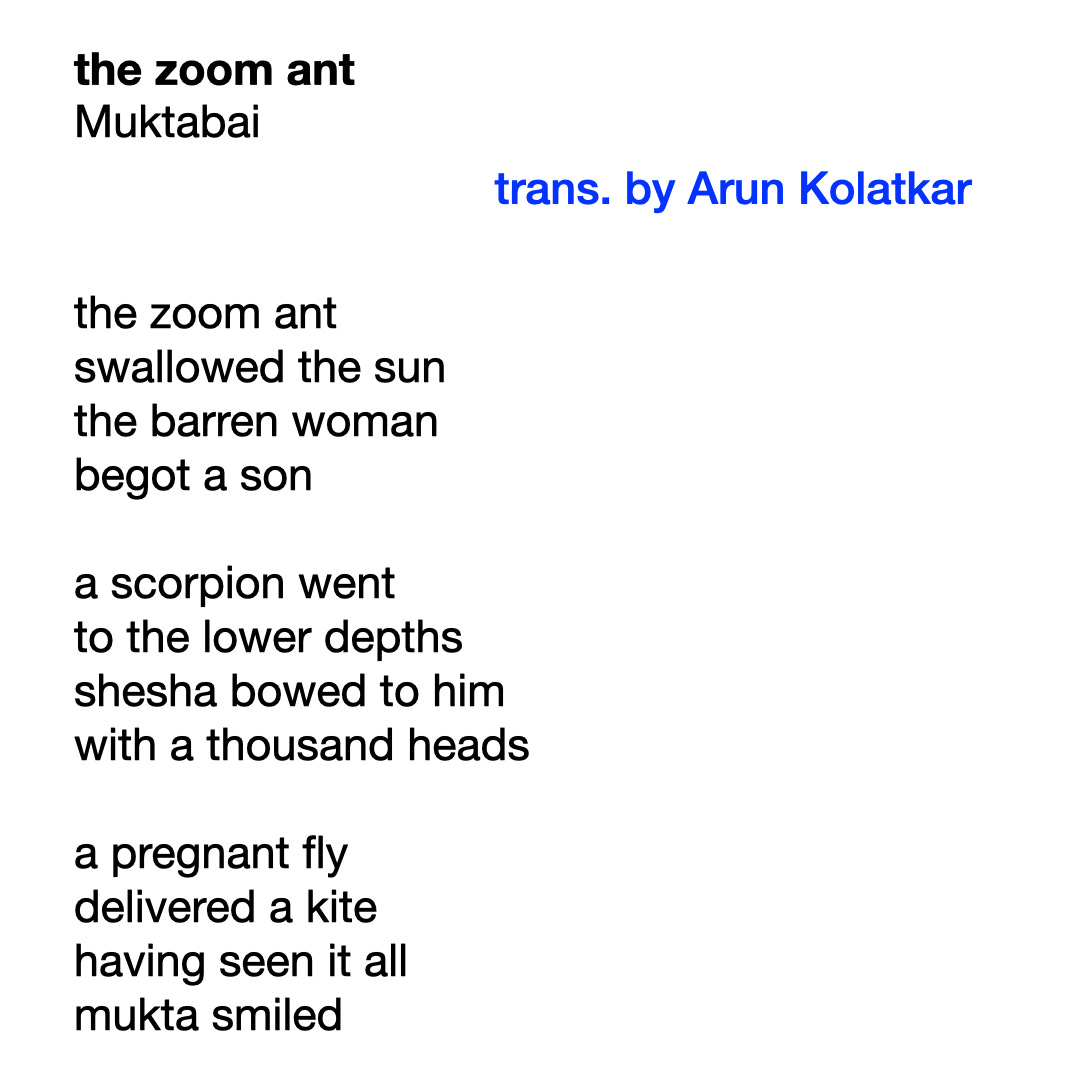

To round off today’s commentary, I share a Kolatkar translation of the Bhakti

poet-prophet Muktabai, along with the Marathi original. Both texts remind me of Kabir’s ulatbaansi.

Hope you, and your loved, are finding meaning and the space to create. Do write to poetly@pm.me if you have any questions, queries, or comments. I will write back as soon as I find the space, and the time.

If you like what you read, do consider ‘buying me a coffee’.