Last week I saw Kapil Sharma’s stand-up special- “I’m not done yet”. Apart from it being the complete opposite of humour, one thing that stood out for me was the palpable awkwardness with which he made some of his “political” jokes. It felt like he was giving a performance at Rajya Sabha, and there were commandos waiting outside who would swoop in at any moment, if he slipped up and made any kind of anti-establishment comment. The upper middle class patrons seated neatly around satin tables, at their evening best, held up the illusion. He was clearly out of his depth. The special, not even fully scripted by him, said more about the platform’s desperate attempt to capture a different fanbase than anything else - to balance the urban, ‘young’ audience with what they imagined were small town aspirational sensibilities. It seemed directed at those “middle-class” youth who were handling Papa ka business, while secretly harbouring broken dreams of becoming kalakars. Sharma (and Netflix)

simulated a shift to intellectual humour - what they could talk about at their parties, for the most regressive kind of family where the ‘man of the house’ decides what soap to buy based on the latest ad that is showing between primetime Zee TV serials or Times NOW election coverage.

So concerned was he about making the evening as amicable and inoffensive as possible that he ensured that there were an array of anti-Congress jokes to offset the two times he mentioned “the prime minister”, and at one point when a tangential joke about Modi bombed and there was an uncomfortable silence in the audience, he quickly followed it up with - “Don’t misunderstand what I am saying. I don’t want a case put on me!” He went to a lot of trouble to clear his name with reference to an old tweet where he tagged Modi, in the process, portraying himself as a drunk who routinely turned rogue after a couple of shots of Jack Daniels. Somehow, ignoring the many stereotypes and contradictions he slathered on to his act, I watched till the end. The structure of the show - the setting, the narrative arc, the performer, the characters, and the “message” - was more compelling than the content itself.

It is ironic- this impulse to sanitise, to plaster with flowers the imperfect realities we inhabit. It is the marker of an anti-intellectualism, and explains the mediocrity of works of art that are born within an environment where freedom is not a prerequisite.

Good can be radical; evil can never be radical, it can only be extreme, for it possesses neither depth nor any demonic dimension yet — and this is its horror! — it can spread like a fungus over the surface of the earth and lay waste the entire world. Evil comes from a failure to think. It defies thought for as soon as thought tries to engage itself with evil and examine the premises and principles from which it originates, it is frustrated because it finds nothing there. That is the banality of evil.

- Banality of Evil, Hannah Arendt

While Arendt’s dichotomy of good and evil can be further nuanced in the contemporary context, the implications of her ideas are still quite relevant. It is this same drive that is behind the banning of the graphic novel ‘Maus’ by conservatives in charge of school curriculums in Tennessee. Spiegelman has termed this turn of events “Orwellian” and several commentators have registered their alarm about such fascist tendencies. But that word doesn’t scare us anymore, does it? The normalisation of trauma is closely tied with the perpetrator’s evolution in methods of suppression. For instance, articles of propaganda in OpIndia have started using footnotes, and even cite western references for their thinly veiled hate speech. Have you noticed also, that the design skills of government sponsored trolls have gotten much better on social media?

I see this as an assault on language, on the power of the word. It is disturbing - this attempt at sophistication, not in intellectual depth, but in generating ambient noise to distract us from the mediocrity of the claims being bandied about. It struck me that popular comedians routinely writing the threat of imprisonment into their scripts is not ‘normal’ by any standards. Even the highly placed, popular celebrities are signing receipts of approval on the atmosphere of fear. It makes me angry, this violence. It closes the mind to the possibilities of language. I feel the need to make a conscious effort to find newer modes of articulation, to seek out those media texts that retain an element of anarchistic freedom, but also to closely watch those that allow the rot of power to set in. This is urgent, I believe, and I have to remind myself about it constantly.

Without regular white-balancing, how will we know to discern the filters that distort our vision?

***

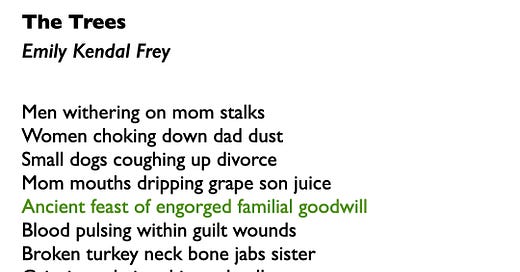

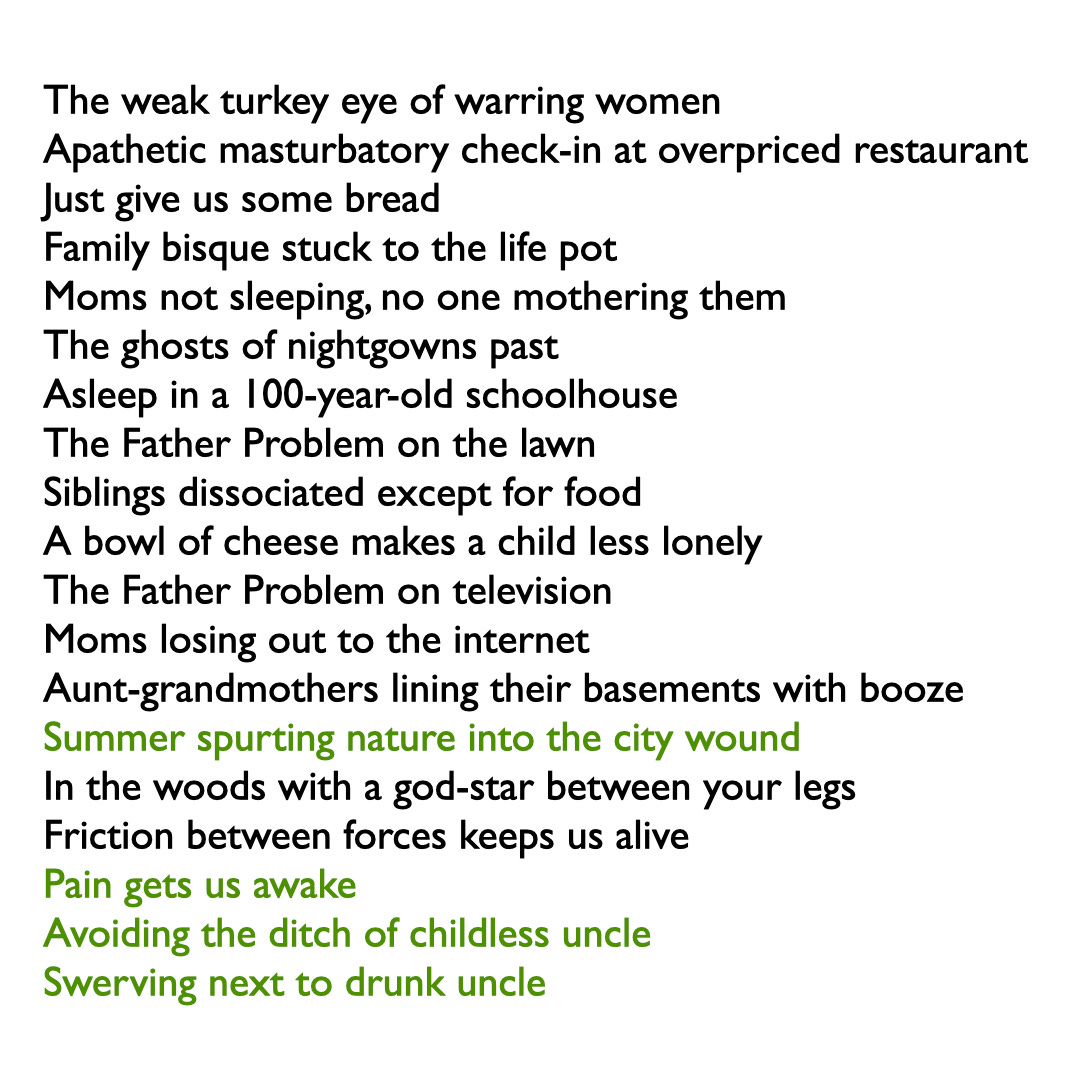

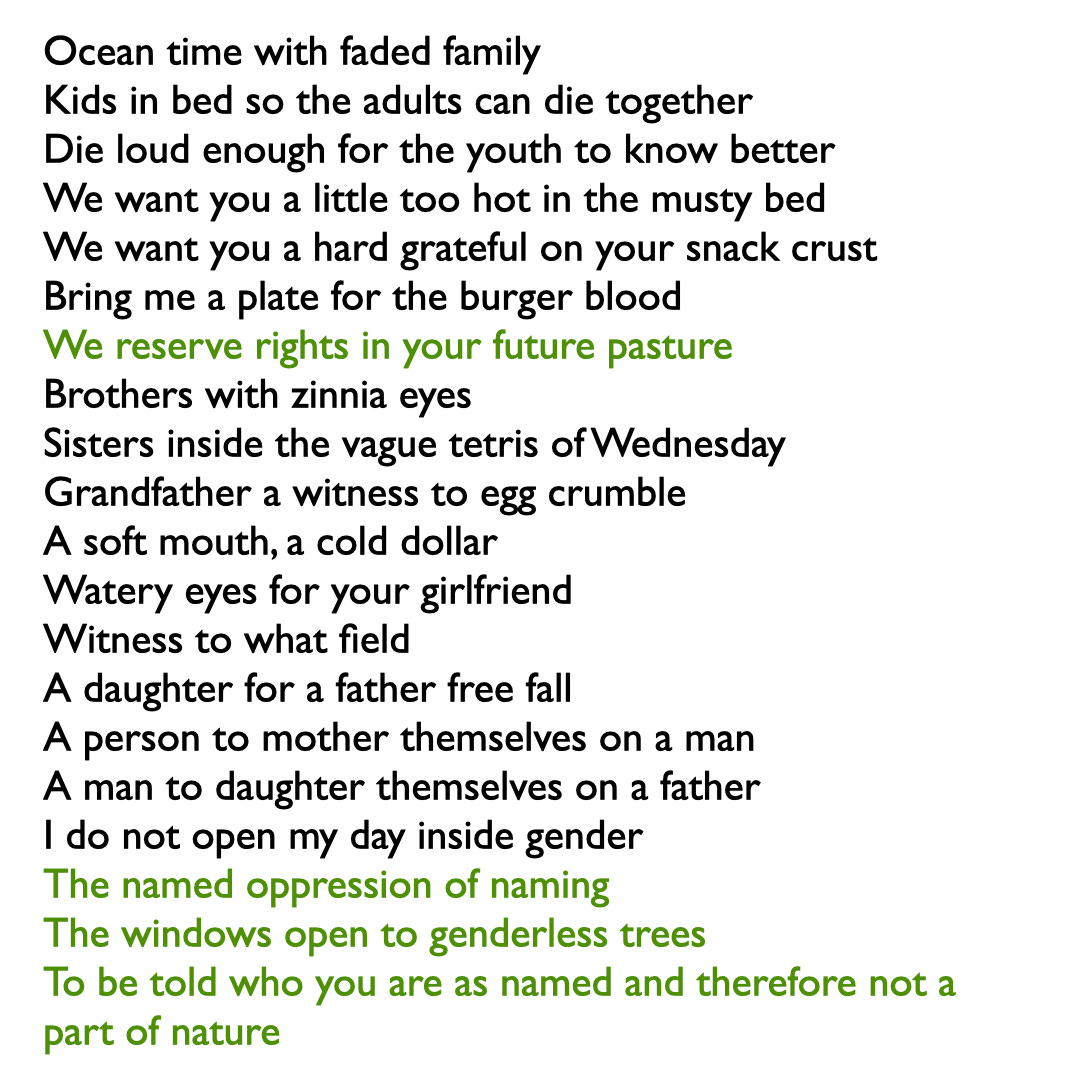

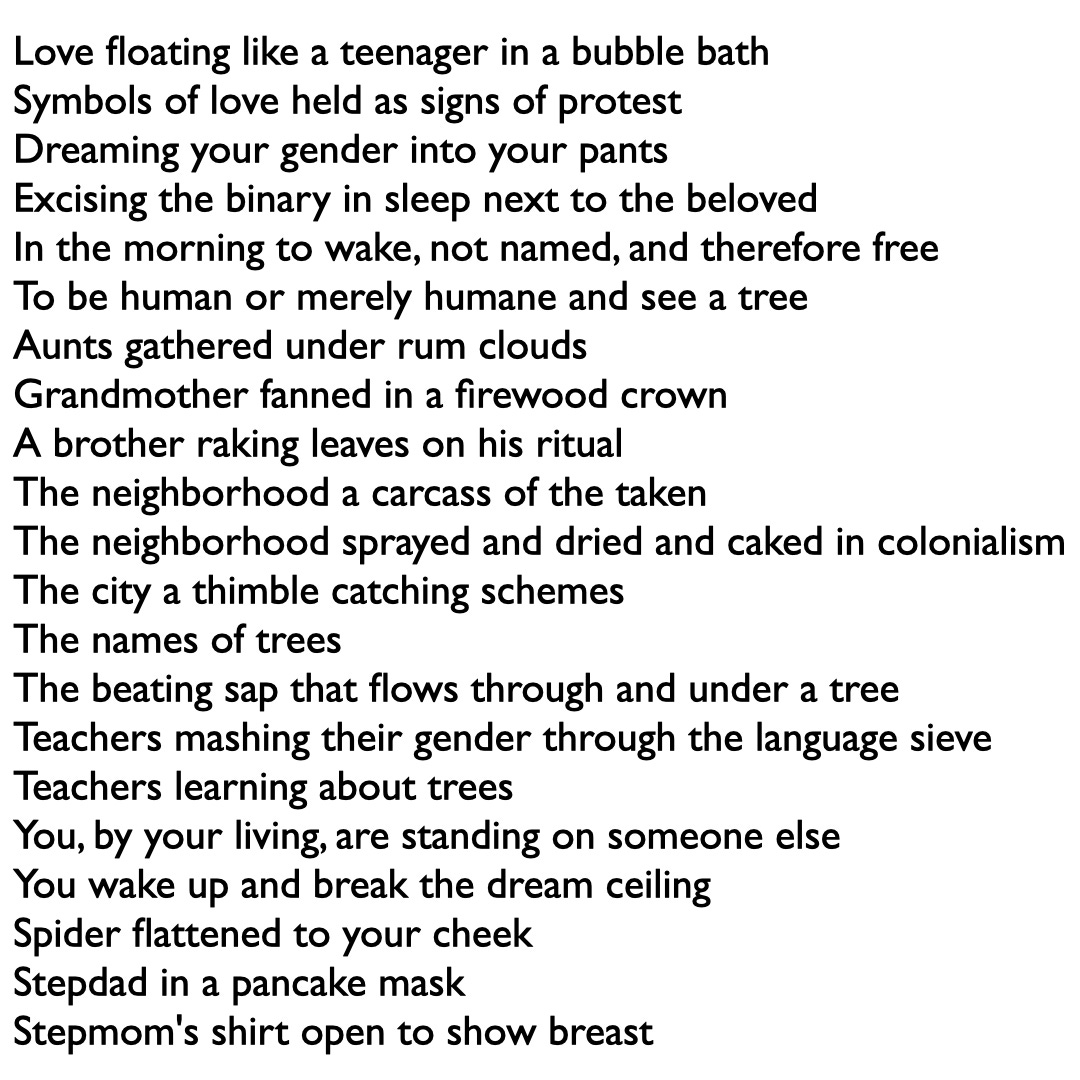

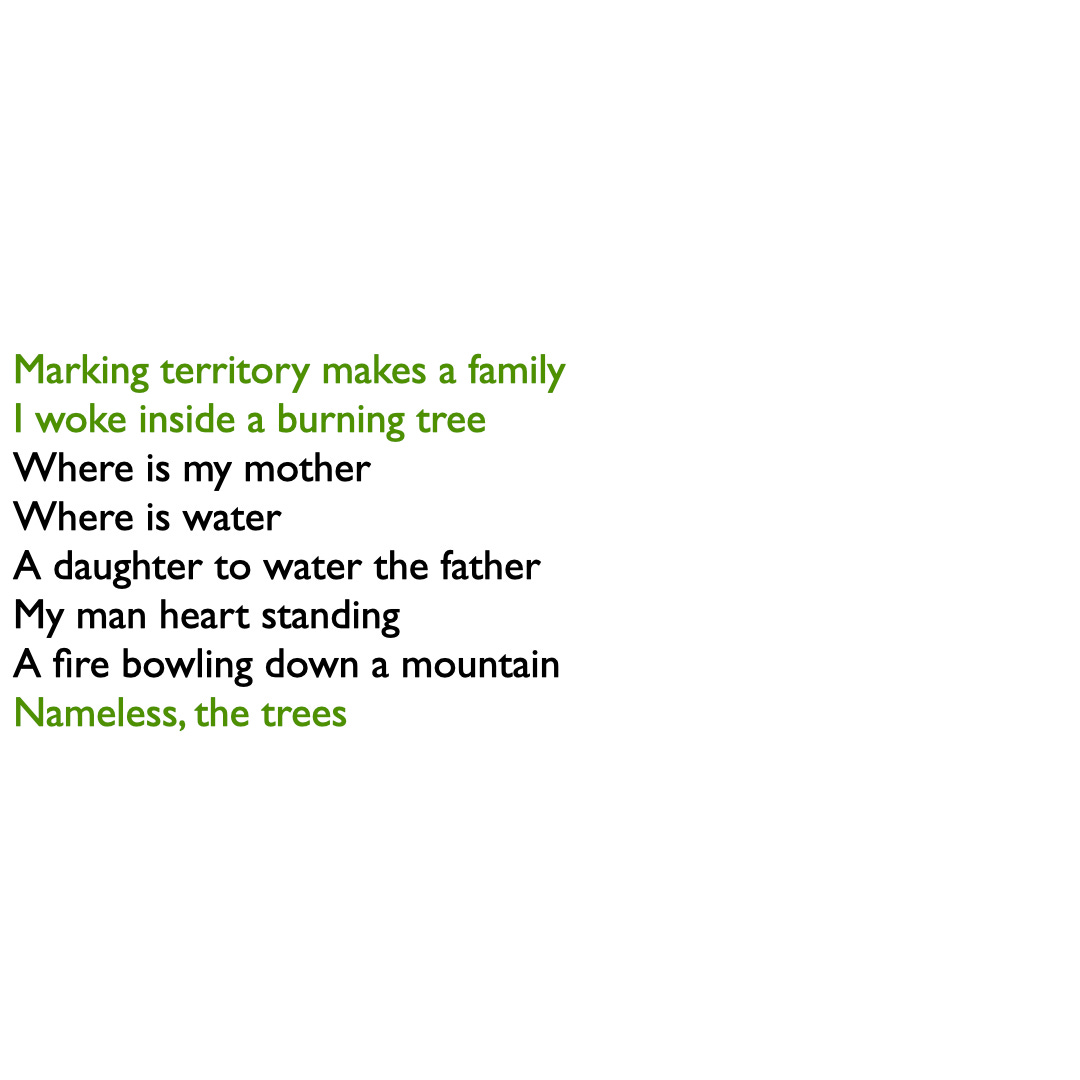

In this context, I want to share with you poetry that does the opposite, words that dance with naked abandon - Emily Kendal Frey’s The Trees. Emily Kendal Frey’s writing is unapologetic and shorn of the trappings of mystical, sublime revelation. It doesn’t try to lead you anywhere - and every line, almost, states profound truths, decontextualising situations with metaphors that only deepen the gaze. The narrative arcs of her poems are wrought with the sudden movements of an artist working with sand on a glass canvas. The fingers flash through vacant spaces, not revealing the form, but by the end of the work, the eyes accustom themselves to a countenance with distinct features. In an interview that is not too recent, she talks about her vision of poetry:

“Writing, I think, is THE most forceful act of hope in destruction. We write to destroy and clear-cut. A good poem is the softest hurricane. We're all up in our tiny rooms, hoping the gods will blow the roof off, are we not?”

Every phrase is driven, not by control, but by an explosive exuberance. The poetry falls on the page with the urgency of sunlight on broken stalks, only serving to illuminate, not heal. Then it scatters. The eye falls first on one thing, and then on another, but the arena is both material and psychological, and she swerves effortlessly through evocative landscapes of vulnerability.

I share with you her poem, Trees - a breathtaking journey in the dark forest of family and social relationships. Swerving through at breakneck speed, the images are strobe-like, arresting insight with staccato bursts of intermittent lightspray.

If you like what you read and agar mann hain, ‘buy me a coffee’.

(Matlab, if you can’t, that’s also fine, obviously. This is a free newsletter.)

(If the portal is not working for some reason, please write to me - poetly@pm.me)

Also. Maja aaya tho share this post, nai?

Thankyou for stepping into this shade in the clearing!

Subscribe if you are not reading this in your inbox, and would like to hang out here more often.