I met the poem I share with you today through a series of sessions I am attending called “Poetry of Resilience” curated by two deeply sensitive and talented poets - Danusha Lameris and James Crews. I have written about and shared Danusha Lameris’s poem Inshallah on Poetly before, and I plan to share a few more poems in the future, of both these delightful curators of feeling.

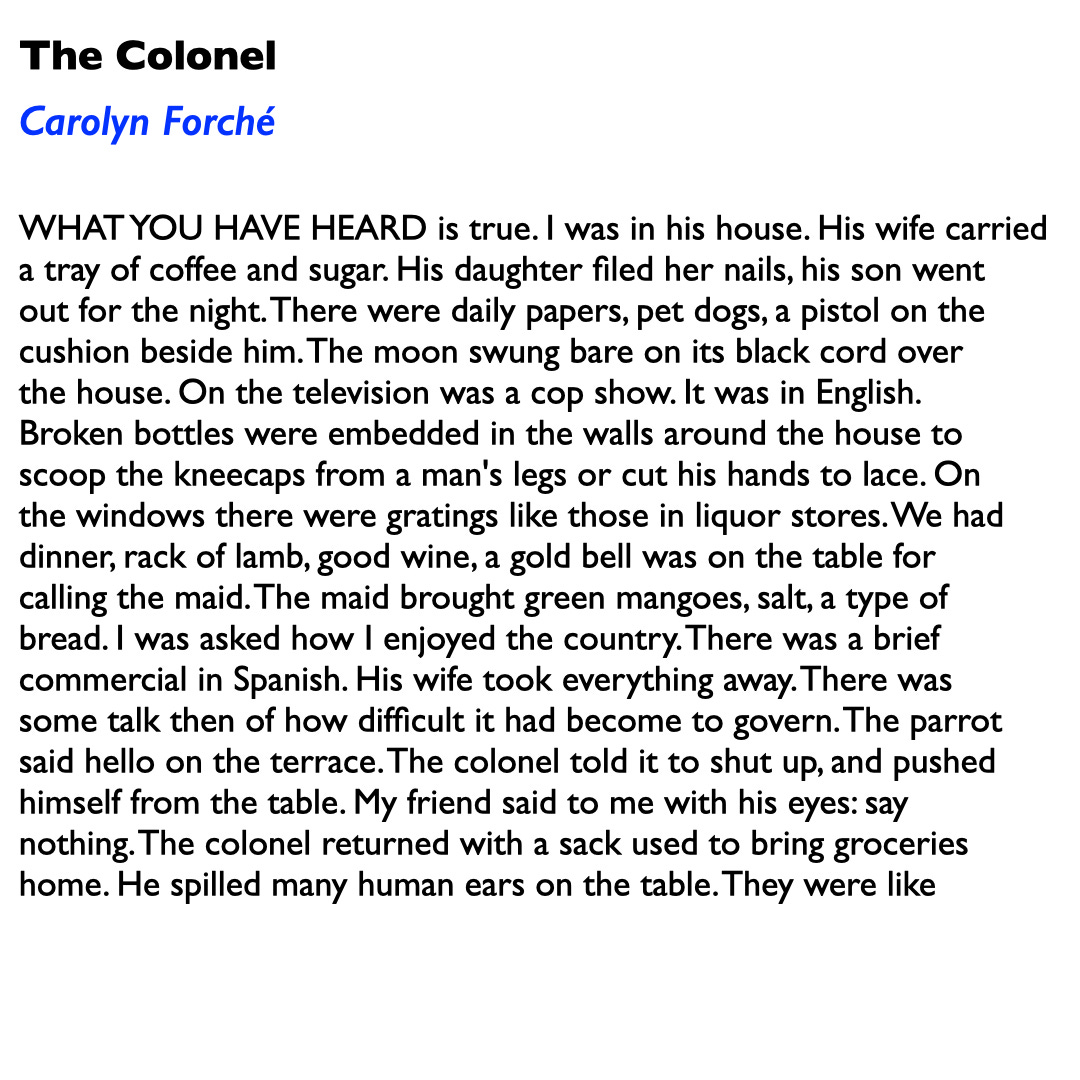

I encountered the work of Carolyn Forche through her anthology called “Poetry of Witness” - “an anthology of poets from all over the world who had endured extremity during the past century—war, imprisonment, torture, exile, house arrest, banning orders, and extreme forms of censorship—experiences of suffering collectively inflicted due to the vicissitudes of history and the depredations of the state.”. She is perhaps, most well known for coining the term “Poetry of Witness”: A collection called “Witness” has been recently published by Red River Press in India, too, a collection that looks at ‘dissent’.

I have thought about this articulation of artists’ expression, and I have heard visual artists, poets and even film-makers talk of their work in this way. I have even felt this while seeing their work. It is an interesting way to think of purpose, and meaning. Maybe it is enough to stand witness, to express with honesty and sensitivity what you have seen, heard, felt, experienced. And in that telling, there is transformation, in that hearing, too there is a moment of shared feeling - of poetry and witnessing that transcends boundaries and lines on a map. To contextualise the poem, I share with you an excerpt from Carolyn Forche’s Blaney Lecture "Not Persuasion, But Transport: The Poetry of Witness" delivered on October 25, 2013, at Poets Forum in New York City, where she talks about her experience of reading ‘The Colonel’ in Libya soon after the ousting of the dictator Colonel Qaddafi:

“I was asked to begin my reading with the poem “The Colonel,” written thirty-four years ago, a poem that arose out of an experience I had while working as a human rights activist in El Salvador. I protested that it was a very old poem, but they insisted and assured me that the poem translated into Arabic rather well…

…When I finished the poem, there was a murmur through the crowd, and I heard a little automatic weapons fire in the air. The crowd seemed to react to the poem in a way I had not expected, with enthusiasm and interest, and it was only later that I was told that they heard this poem about a Salvadoran colonel as a poem about their former dictator, Colonel Qaddafi. They translated the sense of the poem not only into Arabic from English but also into their time and place. I read several more poems and took my seat. During the rest of the readings, I heard more automatic gunfire, and I must have been looking around a bit anxiously because the Libyan man seated beside me finally leaned over and said, “They are firing into the air because they like the poem.” Another first for me. I had never heard AK rifle fire as a form of applause.

After the readings, the audience members crowded around us, shaking our hands, hugging us, some of them with tears in their eyes. One woman, about my age, took both of my hands in hers and said, “This means we are a normal country! That we can have a poetry reading in our city. We are finally a normal country.” Another first. I had never heard it claimed that poetry readings conferred normalcy in human communities, that hosting a poetry reading contributed to the possibility of a future for the city of Tripoli.”

If you are reading this post not in your inbox and you think you might like to receive regular little packets of poetry and commentary in your email, then subscribe to Poetly