Today’s poem and commentary is a guest post by a young Indian poet who thinks deeply and passionately about poetry - Aswin Vijayan. His careful reading of poems, and forays into lesser known truths and interesting insights about existing poets and their cryptic craft (even how their lives are reflected in their poems) fascinate me. I connected with Aswin through a workshop he conducted online on reading Indian poetry, and I have been following his writing and his illuminating sessions on poetry since. The kind of humility and curious wonder that he is drenched in while engaging with the work of poets that are close to him, leaks into his writing, turning it into a breathing thing.

I urge you to engage with the poem he has chosen to share today, and to let him lead you by the hand as he shines a lamp around its deserted sidestreets. I realised as I read them myself, how simply and beautifully the writing reveals an approach, a way of writing into a text, but also addressing the moment of creation, and the relationship one forms with words, and voice. I’m sharing the poem with you first, and then Aswin’s commentary. I feel it would work better that way.

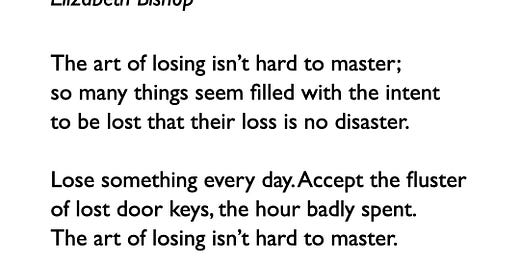

“Loss and grief have become recurrent themes in many of our lives. There are many ways of coping. Reading poetry is one of them as it reminds us, gently, that what we feel have been felt before by others and that they have left behind for us a template for survival. Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “One Art” argues that losing is an art and once mastered, it feels less like a disaster.

It is impossible to overlook the technical brilliance of this poem. Villanelle is a form that is known and recognised for its lack of narrative or conversational possibilities. This is where Bishop’s mastery needs to be noticed. The poem is decidedly conversational. The voice is of someone who is trying to convince someone else (and through that, themselves) that loss is not something to be considered a disaster. This almost joking tone is also punctuated by asides [(Write it)].

She manipulates the rhyme scheme with ease, like when she rhymes “last, or” with “master.” Also incredible is the way she builds momentum within a poetic form that prevents momentum by imposing repetitions. The rhyming pattern demands that in its 19 lines, 13 ends with one sound and 6 with another. Two lines, the first and third of the first stanza, repeats themselves four times each. This repetition and recursiveness prevents this form from being narrative or conversational in the hands of a lesser poet.

The “things…filled with the intent/ to be lost” that Bishop’s speaker enumerates in the poem begins at the small scale of everyday occurrences. Car keys, wasted time. Then it accumulates, and the loss is of things that you ought to remember or of dreams. In the fourth stanza, the loss is of places and possessions that form the core of one’s identity, the things that we identify as home. Then the loss is as vast as “two rivers, a continent.”

Finally, when we arrive at the loss that the speaker has so craftily put off admitting, the loss of a person, we realise that it is even vaster than the continent. This accumulation of scale, of loss and the accompanied grief, is achieved by tapping into the possibilities of this extremely restrictive form.

The poem revels in its own irony, though, as it steadily builds on the heaviness of loss that the speaker has had to experience. It is, after all, a confession, “I shan’t have lied”. The speaker is either admitting that they misspoke and that has led to the loss of a valued personal relationship. Or, on the other hand, they are merely lying when they say loss is no disaster. How relatable, these impulses on the face of disastrous loss!”

Aswin is a poet from Kerala, India. He has an MA in Poetry from the Seamus Heaney Centre, Queen’s University Belfast. His poems have been published or are forthcoming in The Bombay Literary Magazine, Verse of Silence, The Tangerine, and Coldnoon among others. He is also the Managing Editor at The Quarantine Train.

You can follow Aswin on instagram here.