The moon is almost full today. almost. Sometimes I wonder if I can ever see the moon without it being caught between the leafless branches of its mythology. For a split second when I look up in the darkness of this winter night, the moon is alone, unflinching, quiet. Then the world enters, and perhaps, at some subsequent moment, the urge to share the image surfaces. Is it like this with works of art that have been tainted by the dissonant biographies of their creators? How do the technologies of the self colour the text? Is the word always haunted by the shadowy presence of the author? Barthes counselled us about the death of the author, and Foucault built on that critique, also bringing in the question of oeuvre, among other things. I have no answers, but today, reading Sudeshna Rana’s tender and sensitive musings on the subject, I feel some movement in my own exploration of this unnerving terrain. Rana writes with feeling, and for her, the past is an intimate friend, who sits quietly in the room of the present, as she gestures with a realism that is not devoid of the quiet intimacy of connection. This mixture of wonder and shock, is precious, and it makes me think of the ways in which art enters our lives, how it becomes intuition, how it resurfaces as moral uncertainty, and strength of perspective. I am truly grateful to be sharing this commentary with you today. It is not easy to write about the twin impulses of love, in art, and violence, in the artist. It is not easy to empty the soul into the crucible of poetry.

Isn’t it wonderful how archiving one’s lives is such a natural thing for adolescence!

So many of us still have old school reports, diaries, albums, and an ounce of nostalgia buried somewhere we can always return to. When the present is too much, and overwhelming, the past feels like a weighted blanket, too cosy to get out of on a cold winter morning. I had once read that your brain is programmed to purge bad memories. I wonder if the same applies to our interactions with poetry? Do we try to remember the poems that bring joys and repress the ones that speak of woe?

Most of the visceral memories of my life are somehow linked to poetry in a way. Like the first time I read Sylvia Plath’s Mirror in 8th grade. Sitting inside a stiff and hot classroom, with a hand inching towards a packet of biscuits hidden inside the school bag underneath my desk. The hazy recollection of the girl sitting next to me drawing a cartoon of a woman with a round bindi and large protruding lips, a child’s rendition of Jamini Roy on my textbook. Finally, the bell rang, but my eyes remained fixed on the words:

In me she has drowned a young girl, and in me an old woman

Rises toward her day after day, like a terrible fish.

I remember the “terrible fish” looking out of the book at me at the end of that lesson. At present, I think that was the moment of transition – from a child to girl. Yet, these days, I like to remember the frivolities of girlhood and the little joys.

Few years later, Faiz beckoned youth and revolution. Soon, the spring and cherry trees of Pablo Neruda inflamed desire. But Neruda also brought a certain unease, now that I could not see the world anymore from a child’s eyes. After all, the discourse cannot forget that Neruda was also a rapist.

Poetry has a way of sinking in your soul and getting enmeshed with your feelings and senses. To the point where you cannot separate the verses from your being. Did you learn to love from poetry or did poetry come from love? Does art imitate life or life imitates art?

Well, I don’t know the answer. Neither, I presume, does anyone else, really. It brings us to another chicken and egg question — about the art and the artist — and are they separate or connected entities. Should we disconnect ourselves from the subjective experiences of the artist? Can we?

Are the para-social relationships we form with our poetic geniuses as absurd as our celebrity crushes?

Could that day in class reading Ted Hughes’ Hawk Roosting have been the moment of realisation that, this is, after all — a man’s world? It’s a hazy memory: I can still hear that all-too-comforting sound of the tram lines, from the street across the cold, high-ceilinged classroom of our college.

Turning to my friend, who looks resplendent in her kalamkari kurti, I asked “Do you think it’s a man’s world?” She nods — sadly and cynically. And you nod — sadly and cynically.

Between my hooked head and hooked feet:

Or in sleep, rehearse perfect kills and eat.

Hughes’s Darwinian outlook on life felt like a hostile linguistic takeover in the language of the coloniser, but it also, ruefully I must admit, inspires admiration.

Those sparse compositions of words and the sudden transportation of one’s self by the sheer power of Hughes is all I like to remember now about that class. Not the rest of it. The carbon monoxide, Assia Wevill and her child. I try not to think about it. But I, inevitably, do.

Ceasing my rambling, let’s return to the point where I mentioned the links between poetry and memory. And how intimate and deeply personal these connections are tied to each of us who have poetry embedded in our lives.

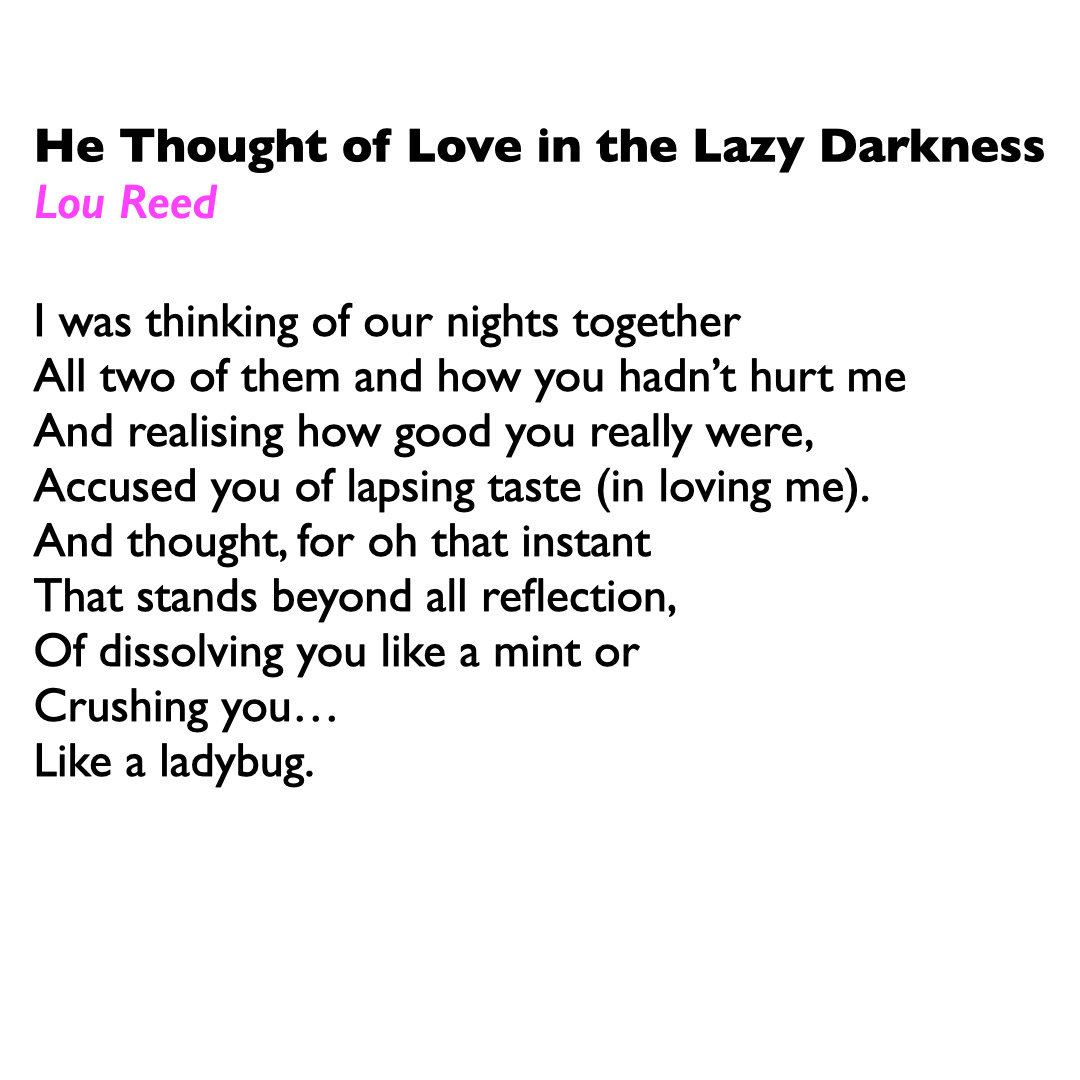

Music, too, is a linking portal to memories, especially when it is whetted with poetic transposition. It is why the poet-musicians of our times are so revered in the space of art and culture. When Bob Dylan received the Nobel Prize for Literature, the links between poetry and song-writing received mainstream adulation. Yet, there was another man whose body of work mirrored this straddling of the twin worlds of music and poetry: Lou Reed from The Velvet Underground. While Andy Warhol’s stint as the band’s manager gave the band a devoted audience, it was Lewis Allan Reed or Lou Reed as he had fashioned himself, who created the dark and poetic legacy of the band in rock-n-roll. In fact, when he quit the band and started his solo career, he had segued into a career of a pakka New Yorker poet who recited his verse alongside the likes of Alan Ginsberg. In his early days, Reed studied under and formed a lasting friendship with the poet Delmore Schwartz, best known for his short story, In Dreams Begin Responsibilities, at Syracuse University. His influence in Reed’s life trickled into his songwriting and poetry.

Reminiscent of Beat poetry, it is in the simplicity of words that Reed is able to paint palpable narratives through his music. The song lyrics of such masterpieces like “Venus in Furs,” “Pale Blue Eye” and “Walk on the Wild Side” is a mixture of poetic brevity and evocative imagery. His work is also a strange, guilty pleasure for those, like myself, who are burdened with literary proclivities. A lot of his songs are ekphrastic in nature while channelling a highly provocative “gutter realism”. The intertextuality gives them a sense of historicity, as his songs’ characters borrow references from the literary canon, from Leopold von Sacher-Masoch to Shakespeare.

It is almost impossible to be untouched by Reed’s music and a huge part of his impact is his poetic genius. But for those who personally knew him, he could be a racist and misogynistic abuser. Further complicating things were his painful experiences with mental illness and institutional homophobia.

Most poetry is best read aloud. And when combined with experimental guitar played by Reed, his words have a universal power. As an influential, albeit controversial, figure in the history of rock music, he complicates our collective horror when cultural or artistic heroes turn into “monsters.”

This is not an apologist diatribe. Maybe it’s the coping mechanism of a mind obsessed with the art of language.

In the end, it is the memory of a day in life when love seemed possible and so did its impermanence. When I had stumbled upon Lou Reed’s Perfect Day, his poetry came hurtling down to a place where only love lingers over a secret ocean of tenderness. And it latched onto me, the way the opacity of another person haunts relationships.

So, I leave you with two poems/songs from Lou that I associate with the vulnerability of love and its destructive power. Maybe you can find new meanings in these love poems.

Sudeshna Rana is a writer, poet, and editor with bylines in Smashboard, Feminism in India, Cocoa & Jasmine Magazine and Red River Publishing. Her piece on female friendship will appear in an anthology published by Yoda Press. A recipient of South Asia Speaks 2022 fellowship, she is currently writing an ecofeminist account of Dhanbad, the coal capital of India. Her writings focus on female friendships, gender representations in media and the relationship between culture and climate crisis.

Incidentally, for any interested writers, Rana is collaborating with Academic-ish, a platform dedicated to writing and issues from the Global South, to conduct a session on how to nurture a writing practice. Please find the sign-up form below.

https://forms.gle/q1SioUuais9MrSqL9

I hope you are well!

If you like what you read, do consider ‘buying me a coffee’.

Note: Those, not in India, who’d like to support the work I do at Poetly, write to me - poetly@pm.me.

If you wanna share this post…