I feel like most commentaries that I offer in this space respond to the pressing question of why one reads poetry. Poetry offers solace to the searching soul, yes, but the practice of creative reading is an attempt to learn the cadences of insight that art offers. I derive joy in the thrill of creative connections, and in the comfortable uncertainty that those who have gone before me have grappled with the same questions. The title of Ranjit' Hoskote’s translation of Mir’s poetry “The Homeland’s an Ocean” pulled me into this vortex of synchronicity, for many years ago, as a college-going fellow, I myself had written a poem that used the metaphor of a “river” for “home”, and explored the question of movement and stillness. This theme has recurred through my writing in different ways with different imagery, but the generative tension remains. A few years later, when I encountered Ramanujan’s masterful translation of Basavanna I marvelled again at this realisation of having grappled with the same questions and encountered a kind of collective “pool” that we who who write, sip from - “Listen O Lord of the meeting rivers,/ things standing shall fall,/ but the moving ever shall stay”. I have referred to this current of associations in previous commentaries.

Here’s the Mir couplet translated by Hoskote that, again explores the tensions between movement and stillness. I see this as another bead in the necklace of profoundly mystical poetic musings on the nature of belonging:

Hoskote’s take on this “continuity” affirms my belief in such connections, and the archiving of these intertextualities, From his introduction about Mir Taqi Mir:

“But poets do not live on through monuments; they live in our hearts and on our tongues. The poems that I have selected and translated here are offered in homage to this continuity. I came to Mir after many years of working on translations of Ghalib’s poetry; I knocked at his door.. on Ghalib’s recommendation. Mir … is a timely poet, one whose work releases itself with renewed urgency…establishing its continuing relevance across the barriers of language. Indeed, it reshapes those barriers into new and necessary bridges”

- From Ranjit Hoskote’s Introduction, The Homeland’s an Ocean, (2024, Penguin)

The introduction positions Mir differently from others - as a lover and romantic, yes - but also as a political poet keenly bearing witness to the social upheavals of his times - similar to the way some commentators speak of Ghalib’s witnessing of the 1857 mutiny, and carnage.

The keen reader surrenders to the search for human connections, biographical resonances, even character motivations in non-human subjects perceived in artistic work. This drive is unavoidable, and I attempt, in my reading of scholarly work to discern innovative paths of narrating the human story. The introductory essay is masterful in that it draws from diverse authoritative scholarly sources, while, at the same time historically contextualising the poet’s lifeworld, even as it embraces a defamiliarisation from widespread critical tropes of reading Urdu poetry. Hoskote urges readers to move out of Urdu literary scholarship’s “nostalgic” insularity, and place Mir in a context of global literary exemplars. This approach is instructive, and, one that I have unconsciously imbibed as non-linear association, in my own comparative artistic studies. “Mir was the contemporary of Goethe, Blake, Schiller, and Wordsworth”. Located within this pantheon, and against the context of Romanticism, or Modernism, the work of the Urdu poets surges beyond the petty critiques and chronological comparisons (such as between Mir and Ghalib, or Mir, and Sauda) that are motivated by the immediate lived socialities of the poets - the ‘mood’ of the times, so to speak.

Hoskote draws a compelling timeline of Mir’s everyday, and paints a picture of the living breathing monster that is the ravaged city of Delhi during the decline of the Mughal empire, and the various political “plunderings” that punctuated his long life (He lived till the age of 87).

As I read the contextualising essay, and the cited verses, I started to see myself in the poet’s struggles and feigned aloofness, the notions of gugtagu and rozmarrah (the demotic or ordinary, as opposed to simplicity or saadgi that previous commentator attributed to Mir). I was fascinated, also, by the contextualisation of Mir’s poetic practice among peers in a milieu of “affective communities” or what, perhaps, Lave and Wenger, might call “communities of practice”. Hoskote cites the “ahl-e-zauq” through the work of the well-known cultural theorist Katherine Schofield - a figure like the rasika of Sanskrit aesthetics, and the communities that they were a part of. The alignment of art with the seasons, the body politic, and the soul, forms a compelling cultural line that we draw on even today in our publishing and artisanal practices. Mir’s poetic laments for intellectual and artistic affinity (even his critiques of fellow poets) acquire deeper meaning within “season-appropriate musical performances, poetic ensembles and cultural practices that were enacted across a web of scales and locations”.

I urge you to read the introductory essay, as a poet, to seek and understand the motivations and passions that undergird creative praxis. Read it as an aficionado of art and literary history, and while it gives you important annotations to the social patterns and intricacies of that epoch, it opens enquiries, through informed allusions, into the layered scholarship of poetry and poetics, language and culture, aesthetics and identity. Even as the translations of couplets embody the mystic courier-work of linguistic transmission, the introductory essay performs the secondary and important function of cultural translation.

I share below a selection from Hoskote’s 150 selected couplets or asha’ar (it is a formal choice to translate not entire ghazals but individual shers). It must be noted that this carefully curated selection draws from a repository of “a huge body of primary-source material-- six divans [dīvān], totaling 1,916 ghazals-- from which no shorter selection was ever made by the poet himself” (from Francis Pritchett’s website, a student of the legend Shamsur Rahman Faruqi - Hoskote, in all humility cites Pritchett’s web-archive as the primary source material, and asserts his intellectual debt to both these commentators).

Yes, reader, I read this as a call-to-action the way I read Faiz’s bol ke lab azad hain tere. Another Ars Poetica:

And then the metaphor of the city, and the town, for the heart…

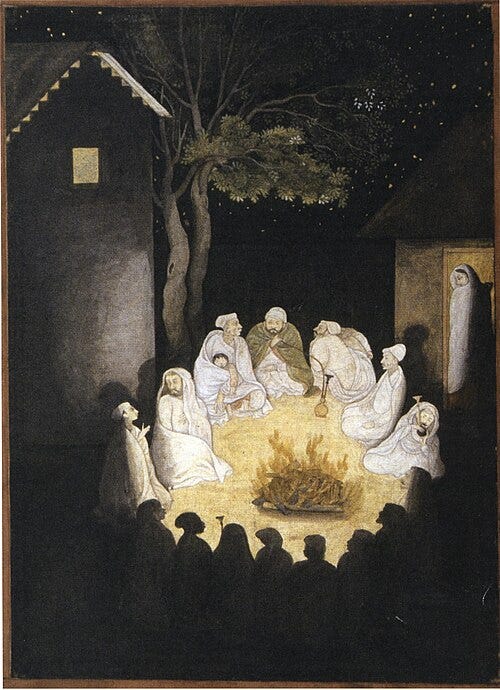

One of my favourite couplets invoked in my imagination a favourite painting by Nainsukh of Guler.

Here is the painting (Wikimedia Commons)

and then we enter the realm of the imagination… what is true? authentic? what is real and what is constructed? what is belief, and what dream?

Kar-khanah, here has been translated as “studio”.

Another couplet I enjoyed for its unique word-choice… “jaan” as “lifespring”…

Love, of course. I return again and again to the linguistic construction which interrogates the long history in Western and non-western cultural discourse of locating the heart as the seat of emotions - What does it mean to learn a thing “by heart”? How does sensation turn into feeling via the semi-cognitive activity of emotion? What is the cultural milieu of this exploration in poetry?

Note: All translations and excerpts are from “The Homeland’s an Ocean”, Mir Taqi Mir, translated from the Urdu by Ranjit Hoskote, Penguin India.

Hope you, and your loved, are finding meaning and the space to create. Do write to poetly@pm.me if you have any questions, queries, or comments. I will write back as soon as I find the space, and the time.

If you like what you read, do consider ‘buying me a coffee’.