Jorie Graham via Al Sufi, Basho and Issa

The poetic turn

Two dots make a line, a third makes a map, but vantage is for birds. We are still grappling with flight. This is the anxiety of belonging, and the inertia of roots. Three dots also make a constellation, but the metaphor is rooted in the eye of the mind, a body tethered to history, and sharpened on the rolling stone of the current moment. The shards that fly out are something that is beyond subjective perception. For the moment, I will not try to conjure up an image worthy enough to contain the sensorial miasmas that smear the symbolic realities we construct for each other. I do not believe, however, that this is an idle pursuit. To know that reality is an illusion held together by the vulnerability of conscious thought, where there are no real events or happenings, is a liberating feeling. We come closer and closer to a shared experience that is encircled by kindness. It is this acknowledgement of mystic wonder that deposits the nervous crystals of poems and images in the minds of artists, is it not? The certainty of ideology is an acceptance of defeat, a futile attempt to cover ephemeral truths with the gossamer of control. At the most we can imagine a way of seeing, I believe.

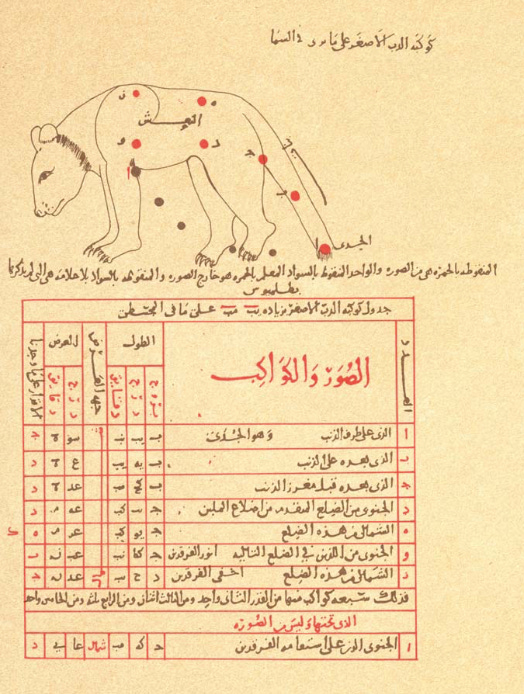

In the year 964, in Shiraz (present day Iran) ‘Abd-al Rahman ibn ‘Umar al Sufi (hereafter Al Sufi), completed a fascinating cartography of the skies he entitled ‘The Book of the Images of Fixed Stars’ (originally written in Arabic, and then, translated into Persian, and later, Latin). Its importance can be gauged by the fact that it was a time of discovery and exploration - in terms of conquest, trade, and knowledge exchange. It was the time when merchants of information and material were translating their wares, reimagining their offerings in the pursuit of learning and wealth. The dream of Babel was being realised as we understood the importance of language, and cultural exchange. Think of what this effort meant for Al Sufi whose contributions included the fields of mathematics, astrology, and alchemy. His work in this critical treatise, was considered a great service to his realm - the book is dedicated to his patron, the Buyid ruler who went by the title ‘Adud al-Dawla (936-983). In essence, considering the maps drawn before him (by others such as Ptolemy), Al Sufi was using the horizon and astronomical indicators of north in the sky to help seafarers chart routes across the world. Here are a few images from a facsimile of the original book. These are the constellations that in contemporary astronomy are called Ursa Minor, Pegasus, and Andromeda.

There are many other works that reproduced, with surprising accuracy, the trajectories of the stars during this time, and in different parts of the world. But what Western commentators today call the Persian Empire, produced works that have built the very foundations of this domain. I find Al-Sufi’s positionality and particular taxonomy interesting, also because it marks, for me, a kind of creative translation of symbolic approximations with very little reference. He was making sense of a perceived reality without any of the tools that science has afforded us in the last millennium. Al-Sufi was, for all practical purposes, taking photographs of the sky. He was drawing ‘fixed images of stars’ (groups of stars to be more specific), with mathematical precision and aesthetic flair - his interpretations were addressed by Islamic and pre-Islamic lore, mythology, and the specificities of his cultural context. It is a work of great concentration, that has isolated a moment in the time of objects that move very slowly. Think about our own vision of the stars. When we look up we are often seeing the glow of stars that are very far from us, and so we are seeing them as they were, sometimes thousands of light years away. Our skies are great miniature paintings that were made a long time ago.

How, in this shifting cosmic seismology can one expect any sort of certainty, or ideological thrift?

Modern science tells us that the more we know about the world, the more we find indications of its eternal changeability - from the largest to the smallest of elements. The pursuit of poets,artists, scientists and polymaths is driven by this most primordial act of seeing, but also a radical acceptance of its limits. I see this radical acceptance as a creative act, even a ‘poetic’ one (yes, yes, there it is…)

Jorie Graham talks about this in an essay entitled ‘At the border’ while describing ‘utterable and unutterable realities’:

“…The capacity to ‘express’ the ineffable, the inexpressible, the emissary of the nonverbal territories of intuition, deep paradox, conflicting bodily impulses, as well as profoundly present yet nonlanguaged spiritual insights, even certain emotional crisis states–these are the wondrous haul that the nets of ‘deep image,’ ‘collective emotive image,’ haiku image-clusters, musical effects of all kinds (truths only introduced via metrical variation, for example), and the many hinge actions in poetry (turns, leaps, associations, lacunae) bring onto the shore of the made for us. The astonishments of poetry, for me, reside most vividly in its capacity to make a reader receive utterable and unutterable realities at once.”

Elsewhere she makes reference to a haiku by Issa, that she translated:

I share here her particular reading of the poem, because it talks, once again about the notion of journeys, of pilgrimage, of a ‘self-in-time’, that contains both the present moment, and the continuous accumulation of ‘nows’ that become both the future and the past:

There is so much of what pilgrimage is in this poem. The field, the going and coming back across it like the verso of the plough, the verse. The man and the stand-in. How you are not the same person when you come back as when you set off. Experience. You have to go and come back. You cannot not take your body. And that ownership is involved. You have to own yourself.

There is another poem by Basho that does this pilgrimage, that talks of many different times, emotions and beings, with a single image. I share two translations below.

and then, the singular…

I have been thinking of all these things against the background of winter, actually; the way the air grows bitter with the sudden realisation of neem leaves in the backyard. Even the city is out to impress, displaying its wares, intent on stepping out in it best colours against the reality of lockdown weekends.

Some time back, through Twitter, I came across a talk by Jorie Graham ‘on description’ in poetry. I recommend this (and her other musings, of course) to anybody interested in reading and writing poetry seriously. It taught me a great deal. There are many interesting ideas Graham offers in this talk, but I want to reference, here, her readings of ‘a description of cold’ in a particular poem - She shares two translations, too, which differ in that one is ‘singular’ and one is ‘plural’. I think this is another poem by Issa, but I could not gauge from the video, for certain.

Deep winter

an oar strikes the water

and the plural

Deep winter

oars strike the water

Graham goes on to point out how one of these is far more evocative, far more distinct than the other. She even goes to the extent of saying that one of them (the singular) constitutes a poem, and the other doesn’t. I see what she means - how the sharpness of winter is somewhat ‘dispersed’ in the multiplicity of oars that implies some ineffable quality of warmth or community. I can see why the first rendition is ‘colder’ than the second.

The various poems that Graham uses and her extrapolations in this talk convey the deep sense of connection and intensity of experience that the act of reading poetry itself can create. One is drawn to this reality, the way Graham herself was drawn to poetry in English when she first heard T. S. Eliot’s Prufrock.

“I ended up in the wrong hallway and I heard these lines of Eliot's flowing out of this doorway—‘I have heard the mermaids singing each to each. / I do not think that they will sing to me.’ And I just went into this huge, long classroom and sat and listened. I had never heard poetry in English before. It was like something being played in the key my soul recognised”

- From No Image There and the Gaze Remains: The Visual in the Work of Jorie Graham (Studies in Major Literary Authors), Catherine Karaguezian

Graham’s sense of perception, as is evident in her poems, has an element of intersensorial delight that freezes the reader to the present, while casting shadows on other temporalities. She has a deep awareness of the limits of this perceived time, but opens up access to an invisible reality with the use of metaphor and poetic time. The critic Willard Spiegelman writes about this paradox of visual impulses in her approach.

“her visual delight in the world is matched by an opposing resistance to the visible…. She has revived the grand ambition of poets like Wordsworth and Stevens but has also undercut the very grounds that make those ambitions possible. She asks us to see the world anew”

I share with you today the very first poem of her first collection of poetry, Hybrids of Plants and of Ghosts (1980), simply because it gives me a way to imagine the present moment and its many riddles. I have often thought of this question- “Is it possible to take a thing on its own terms?”

It is a somewhat vague, whimsical area of enquiry. It implies subjectivity and language. What thing? What terms? But have you got this feeling that there is an inherent separateness in each object. That neem tree that I spoke about a few sentences ago has a language that is distinct from mine or even others’ for that matter. I understand it as ‘bitter’ because of its taste. Somebody else might see it as an ally helping rats climb up the terrace and into our kitchens. But who knows, maybe the tree with its extended limbs is simply a love letter to the winter, a conversation of twig and serrated leaf biding time until food is plenty. Even this last assertion is, as Graham would say, caught in the ‘crisis of subjectivity’. I often think of this invisible ‘other world’.

The thing is, I wonder about The Way Things Work.

Jorie Graham does too, and oh, what a wondering.

Perhaps we can observe this current that she speaks about, this alternating movement that becomes life - a bridge between the objects of desire and the objects of faith.

If you like what you read and agar mann hain, ‘buy me a coffee’.

(Matlab, if you can’t, that’s also fine, obviously. This is a free newsletter.)

(If the portal is not working for some reason, please write to me - poetly@pm.me)

Also. Maja aaya tho share this post, nai?

Thankyou for stepping into this shade in the clearing!

Subscribe if you are not reading this in your inbox, and would like to hang out here more ofen.