“I tried to put the displacement between parenthesis, to put a last period in a long sentence of the sadness of history, personal and public history. But I see nothing except commas. I want to sew the times together. I want to attach one moment to another, to attach childhood to age, to attach the present to the absent and all the presents to all absences, attach exiles to the homeland and to attach what I have imagined to what I see now.”

- From Mourid Barghouti’s I Saw Ramallah

The renowned Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti passed away last Sunday after a life lived mostly in exile. As a writer who took up the Palestinian cause, Barghouti wrote vehemently against the Israeli occupation. His novels and 12 collections of poetry are intimate accounts of displacement, conflict, exile, and the meaning of home. Edward Said described Barghouti’s I saw Ramallah as one of the finest existential accounts of the Palestinian displacement. He quotes Barghouti’s lines about the Palestinian experience of exile in the diaspora: “The Occupation has created a generation of us that have to adore an unknown beloved: distant, difficult, surrounded by guards, by walls, by nuclear missiles, by sheer terror."

There is a word in Arabic which has come to describe the ‘steadfast perseverance’ or the ‘resilience’ of the Palestinian people in their struggle for freedom - sumoud. It is a collective experience of “a strong attachment to the land, even when in exile, but also a mental state that leads to determined action.” There is creativity and the celebration of daily events that make us human even in the face of the most heinous treatment by the oppressors - so sumoud could describe the brazen celebration of a wedding with its attendant rituals within the range of Israeli snipers. The word has come to mean different things - a mental state of resilience and not accepting the status quo, massive displacement, life under occupation, life as a Palestinian with Israeli citizenship, imprisonment, and exile.

The excerpt from I saw Ramallah talks about the inadequacy of language in circumscribing the experience of conflict and enforced distance from the homeland. In this context, sumoud becomes a badge, a shared stain of identity that refuses to go away, a creative reassertion of solidarity and moral integrity. Barghouti’s writing about this experience, like Darwish’s, is raw, as it endeavours to join two unrecognisable fragments. There is always a gulf which he is trying to bridge. Many of his poems talk about the reality of occupation, but also this need to close an open parenthesis, “to attach the present to the absent”.

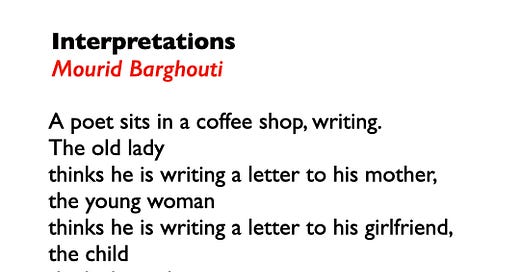

Yesterday a friend and comrade in poetry shared the poem that I’m sharing with you today, and I fell in love with it immediately. It is one of those poems that make their way slowly,insidiously into the the tangle of predatory instincts of a police state, the emotional knot of creativity in a fascist environment, and then explodes in a moment of naked truth. I could not think of anything more apt to describe the state we are in today as a country. I do not need to remind you of all the artists, poets, intellectuals, and activists whose fight for freedom in captivity continues to haunt our present. It is problematic to equate movements, and I am by no means drawing a comparison, but maybe there is something to learn in the collision of cultures of dissent, a common language, a way of sitting together on the barricaded, bullet torn park-bench of sumoud.

Share this post with somebody who’d understand