The music monkey hasn’t jumped off my back yet, it threatens to stay there for a while.

With that warning, I dive into one of my all time favourite poets, today - Frederico Garcia Lorca. I will quote briefly from the introduction to the bilingual edition of his ‘Selected Poems’, just to put a location pin and timestamp on him, so that we can read him in his context, foregrounding him against his contemporaries, and also trace a faint line from his childhood to the poems I share with you today:

Federico García Lorca was born of a well-to-do family on 5 June 1898 in the village of Fuentevaqueros in the plain of Granada. From his father, a prosperous farmer and landowner, and from the family servants Lorca derived a love and knowledge of peasant life and rural lore that served to shape him as a writer. Before he was 4, he knew dozens of folk songs by heart, and such an early acquaintanceship with this material explains its ready assimilation into his poetry.

Lorca is widely considered an innovator par excellence, and as a poet, his oeuvre introduces major literary and artistic movements into Spanish Literature. I’m going to focus specifically on his poetry cycle, Poem of the Cante Jondo.

Cante Jondo, or ‘deep song’, is a vocal style in flamenco. Its roots are in Andalusian folk music. (An aside: Perhaps, broadly speaking, in aesthetic traditions specific to our world, we might have classified it as desi not margi - this is conjecture, of course, and I draw attention to it only to dismiss such classification. Mani Kaul does this beautifully, by placing adivasi music, and indigenous and folk traditions of music, alongside the more “austere” forms - khyaal/dhrupad, or vedic chanting in his film, Dhrupad. This decision did draw some flak from the purists. But then, who cares about them, eh?)

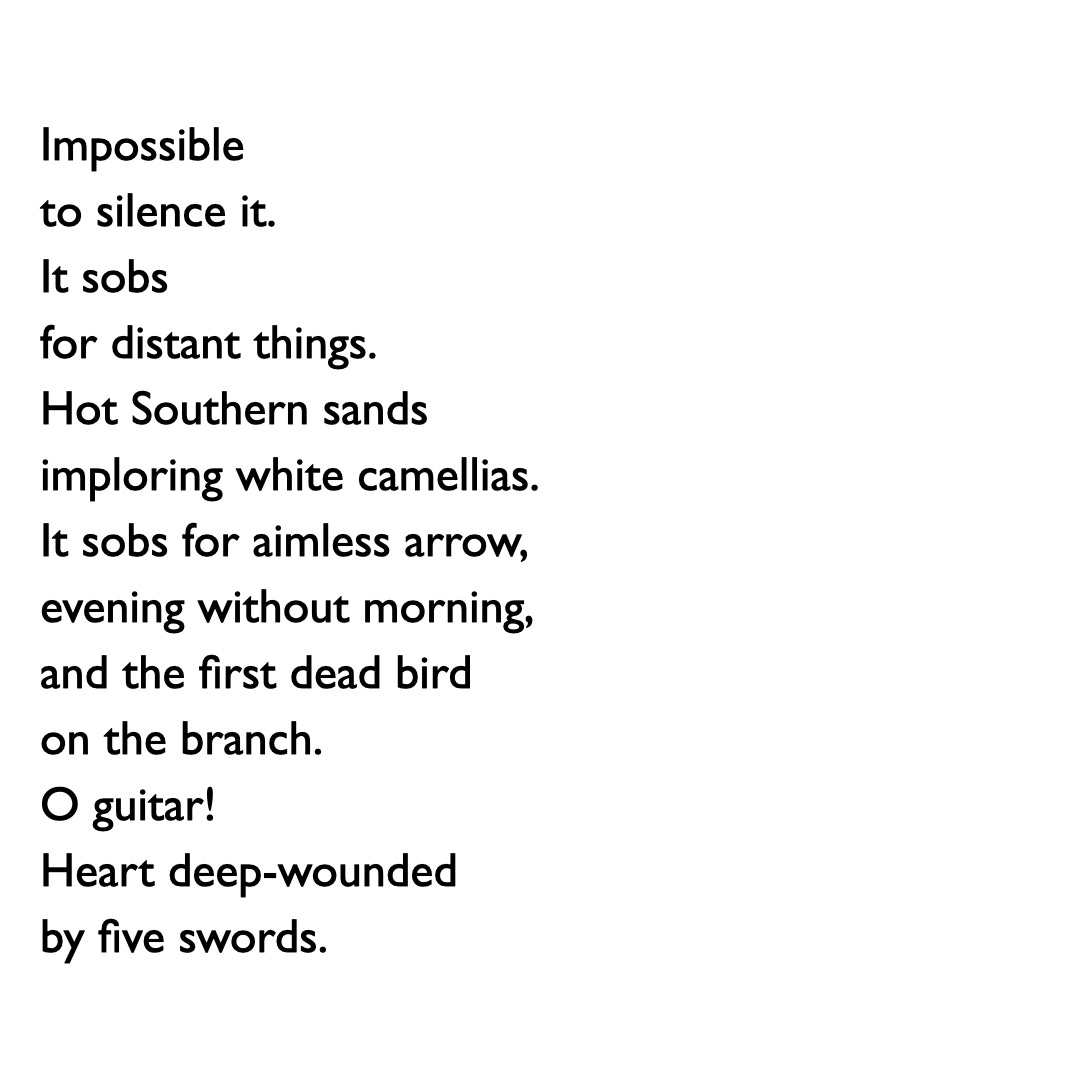

As a musical form, Cante Jondo, holds the aura of being ‘pure’ and ‘untouched’. While talking about the poems that make up this collection Lorca calls it ‘a song without landscape and therefore concentrated in itself and terrible amid the shadow.’ This suggests an attempt to find this ‘shadow’ and draw from its affective landscape, while creating poetry that uses the formal elements of the music, only to enhance, not mimic. But let us look at one of the poems, a famous one:

I like this translation better than the Academy of American poets one. Notice how Lorca distils cultural ethos with a nostalgic transformation of natural currents into a breathing cast of characters. The synecdoche is reined in with a sparseness that is reminiscent of the Flamenco plucking of the guitar that precedes the vocals in the Cante Jondo. From a staccato trickle of feeling - ‘like water,/ like wind/ over snow’ - by the time we reach the ‘evening without morning,/ and the first dead bird/ on the branch’, the melancholy spirit has found the tentative syntax of a broken sentence. ‘A Monotone of sobs’ has become a cautious river. But not yet. The damn bursts in the final flourish as he addresses the guitar directly, now a character birthing music, place, and history.

Here are three more poems that follow The Guitar (trust me it was very hard to only choose three). As I write this, I am ‘spinning’ with Lorca, between the guitar’s moan and the ‘lost town/ of Andalusia weeping!’.

After the ‘Ay!’ must come the silence, of course.

Are you there yet, perched on the slow, blinking eye of contracted woe?

hmm.

Until next time, then…

If you like what you read, do consider ‘buying me a coffee’.

(Matlab, if you can’t, that’s also fine, obviously. This is a free newsletter)

Note: Those, not in India, who’d like to support the work I do at Poetly, do write to me - poetly@pm.me. (Paypal has left the building)

Thanks for reading Poetly! Do subscribe if you are not reading this in your inbox. Cheers!