Under the organdy fabric of a work of art there is a quality of darkness that shifts in dubious registers, silent as the furtive glance of the slowly approaching policeman. We cannot know it, but by its fading echo, the faint pulse of its heart of darkness. Even in works sutured with fragile epiphanies it moans with the persistence of a river whose wandering has receded underground. It is what separates the beautiful from the terrible, the accomplished from the devastating. It is in this kind of quality that the blood of revelation flows. It cannot be stitched with the fingers of craft, nor dreamt with the eye of the mind, it is intuition distilled, and the fire of truth found in a fierce confrontation with that final frontier - death. Even melancholy has offspring These are the oscillating strings that yelp in colourful chords wrought from that enigmatic liquid species of an animal that is called “Duende”.

Let us hear what Lorca has to say about duende

The duende, by contrast, won’t appear if he can’t see the possibility of death, if he doesn’t know he can haunt death’s house, if he’s not certain to shake those branches we all carry, that do not bring, can never bring, consolation.

With idea, sound, gesture, the duende delights in struggling freely with the creator on the edge of the pit. Angel and Muse flee, with violin and compasses, and the duende wounds, and in trying to heal that wound that never heals, lies the strangeness, the inventiveness of a man’s work.

The magic power of a poem consists in it always being filled with duende, in its baptising all who gaze at it with dark water, since with duende it is easier to love, to understand, and be certain of being loved, and being understood, and this struggle for expression and the communication of that expression in poetry sometimes acquires a fatal character.

Lorca’s ‘Theory and Play of the Duende’ is a fascinating essay painted with the blood of eyes torn open with the vision of realities too immortal to be alive. He traces this doublespeak of death as performance to its very root:

In every other country death is an ending. It appears and they close the curtains. Not in Spain. In Spain they open them. Many Spaniards live indoors till the day they die and are carried into the sun. A dead man in Spain is more alive when dead than anywhere else on earth: his profile cuts like the edge of a barber’s razor. Tales of death and the silent contemplation of it are familiar to Spaniards. From Quevedo’s dream of skulls, to Valdés Leal’s putrefying archbishop, and from Marbella in the seventeenth century, dying in childbirth, in the middle of the road….

…a country where what is most important of all finds its ultimate metallic value in death.

Before Lorca visited New York (he arrived there in the August of 1929, “at age thirty-one, in time to witness the collapse of the stock market that sent the city into a tailspin and much of the world into the Great Depression”), he was wide-eyed - having read and seen, about the bustling grandeur of the city, this temple of metropolitan paradise that it was purported to be. But Lorca saw only squallor, and death. In it he saw the absence of the natural, the organic. He saw the murder of humanity, and spun into an intoxicating critique that gave voice to a poetic torrent. I am reminded of that line from the song sung by Kishore Kumar for the film which draws its title from there - Har Koi Chahata Hain Ek Mutthi Aasman.

‘Haunting’ is a word that is often used to describe the cataclysmic insight and lyrical force of Lorca’s ‘Poet in New York’. Pablo Medina and Mark Statman, editors of a recent bilingual edition of the book (with a foreword by the sparkling Edward Hirsch), relocate the poetry within a post 9/11 world:

“Their weakness was our weakness, their impermanence our impermanence. For weeks after the disaster, smoke and dust filled the air, and the prevailing winds carried them uptown to the Bronx, east toward Brooklyn and Queens, west toward New Jersey. That smoke had the strangest smell of wrecked buildings and decaying bodies, which we tried to avoid by closing our windows, by wearing ineffective felt masks, or by holding handkerchiefs to our faces. New York had received a deep wound and we felt those airplanes reach inside us, crash, and burn through our stin-filled morning again and again”

As I read Lorca again, in the staggering matrix of the different cities that I have been to in the last few months, I do not feel despair. I feel a cloying nostalgia for the thing that Lorca sees as lost. For him the city banishes all that is primordial and true - ‘those deserted offices/ swept clean of agony, / that erase the designs of the forest’. Lorca’s poems puncture what he saw as a reckless anthropocentrism - “I have come from the countryside," Lorca said, "and do not believe that man is the most important thing of all.”

He deemed his own time in New York, ‘useful’. This is what I read into the city, this unnerving self obsession, this possibility of equivocating with the urban jungle outside of the cages of our own solipsism. The position of the poet, then, is one of great vantage. After reading his critique one is left with a brooding vacuum filled with the inkswell of his duende. I do not believe that Lorca offers the possibility of redemption, something that even Eliot motions to again and again, even though it eluded him - “I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each./ I do not think that they will sing to me.” Instead Lorca’s poetic rage tears the city apart, and confronts its barrenness, disinterring the stillborn corpse that is the modern human condition.

This is how, for me poetry is testimony, and ultimately, prophecy.

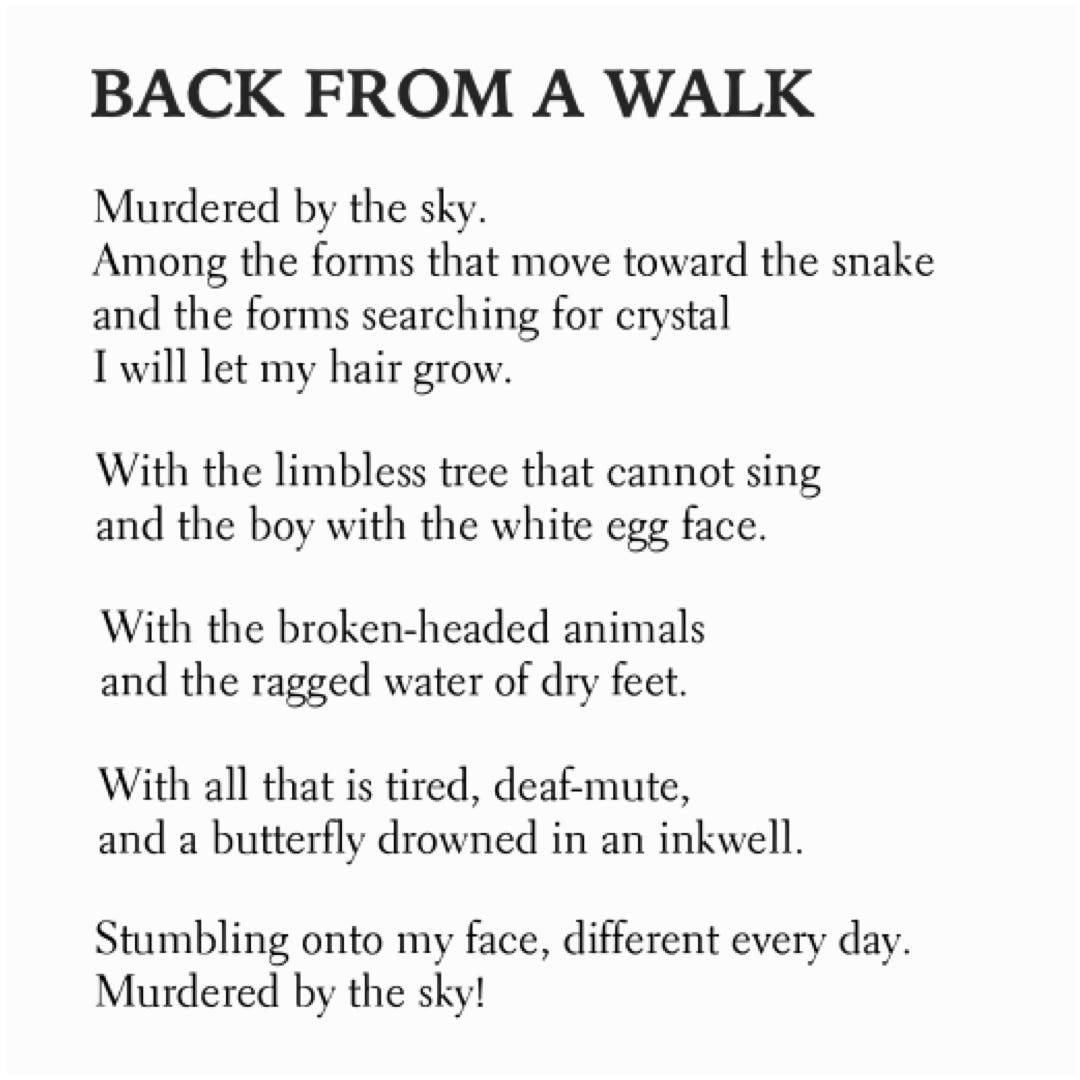

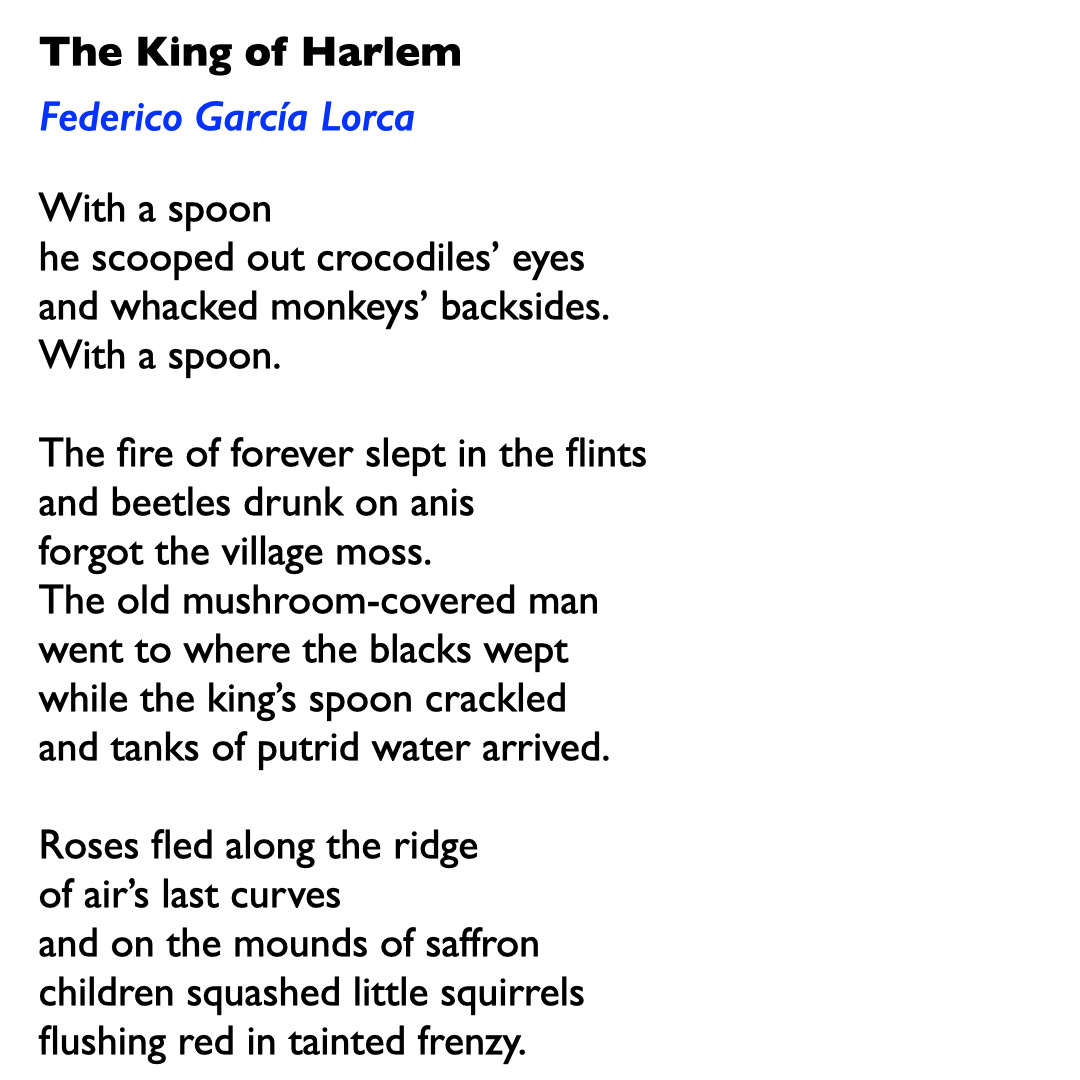

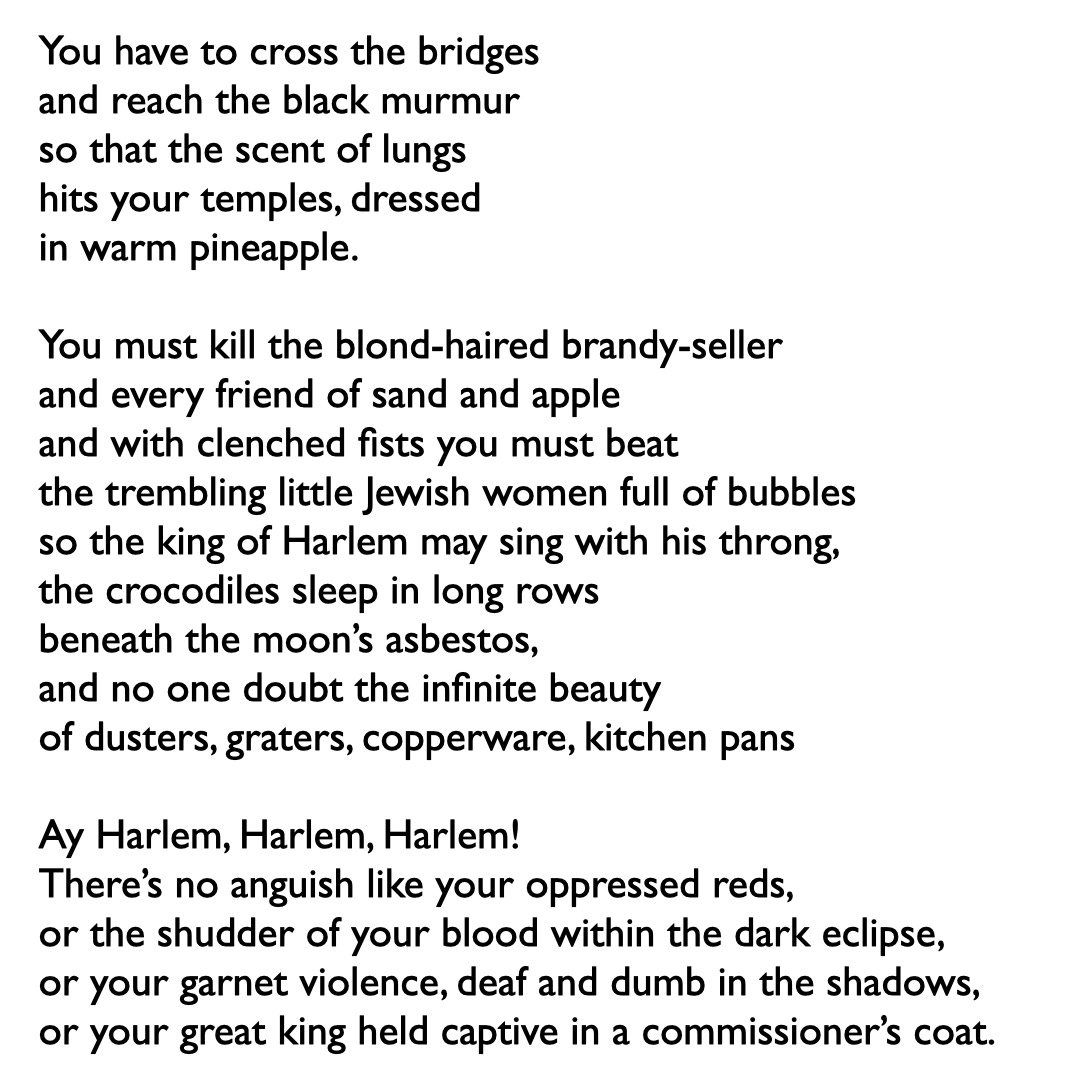

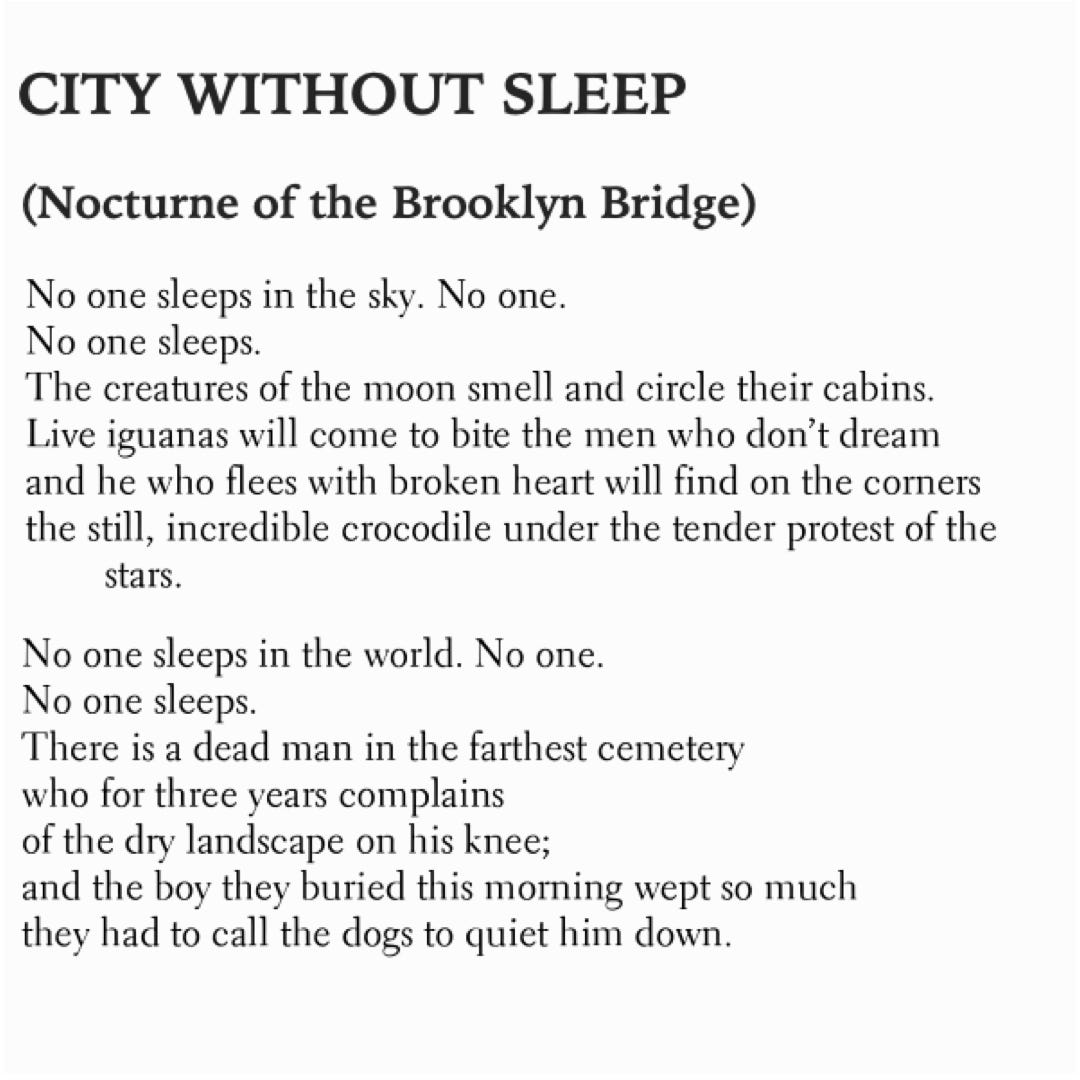

I share with you a few fragments, a heap of broken images (not all are complete poems), from Frederico Garcia Lorca’s ‘Poet in New York’.

If you like what you read, do consider ‘buying me a coffee’.

(Matlab, if you can’t, that’s also fine, obviously. This is a free newsletter)

Note: Those, not in India, who’d like to support the work I do at Poetly, do write to me - poetly@pm.me. (Paypal has left the building)

Thanks for reading Poetly! Do subscribe if you are not reading this in your inbox. Cheers!