I’m superstitious about poetry, maybe even a bit foolishly religious. I accord it a place in my life that is beyond real things, experiences and implications. I often read poetry, the way the pious read signs in nature and infer meaning or draw strength from them. Poems come to us with a kind of astounding serendipity. “Soul poems”, a special category that I repeatedly return to, come to readers at just the right time- poems of such simplicity, and disguised in such ordinary attire that one is surprised by the radiant light that suddenly streams through the seams. These poets who distil light from starburst, and teach words the secret language of kindness are no less than divine, and must be cherished with the silence of the sacred, of prayer. I’ve shared these “soul poems” before - Everything is Waiting for you, The Journey , All you who sleep tonight, The Peace of Wild Things, Sitaaron se aagey jahaan aur bhi hain (to spotlight a few) - and these poems, I hope, become the luminiscent beads that glitter in a necklace of care.

The truth is that any poet who’s seen, who knows the heart of things, allows that light to enter her words. Every poem that talks of the ordinary and the inconsequential, but with undivided attention, beams with a kind of detachment that allows the rays of its enigmatic knowledge to touch every other thing around it - so much so that the poem settles imperceptibly into every context its placed, every heart it touches. That is the power of poetry, and of art. That is how a thing becomes timeless, universal, how language learns immortality.

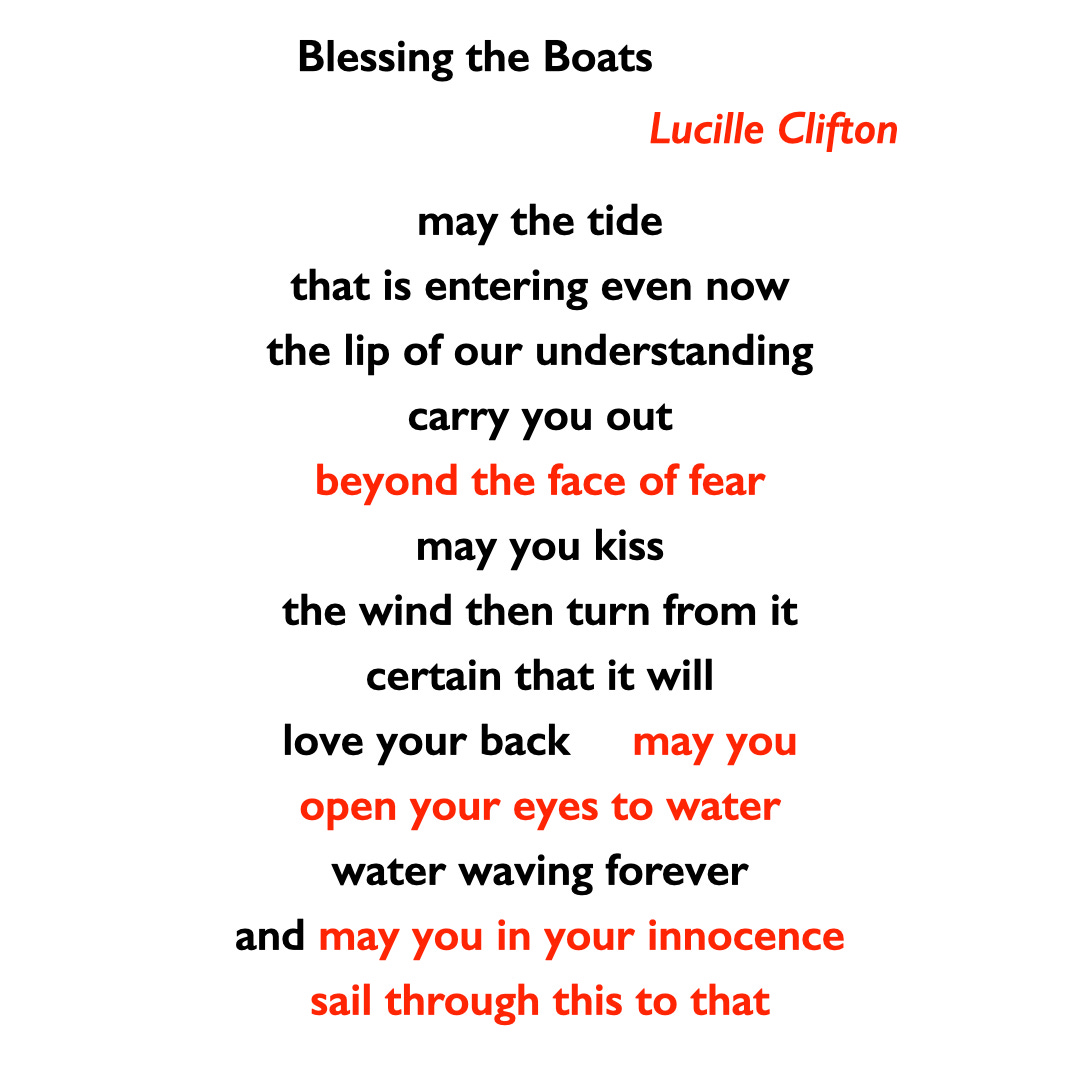

The poem I share today is eternal in the same way. Lucille Clifton’s poems find me at the right time, always. Many of her poems labour to deliver, with lightness, the trials and travails of the black experience in America, but they go beyond, touching the complex geography of the human condition. Her style is simple, direct:

In an American Poetry Review article about Clifton’s work, Robin Becker commented on Clifton’s lean style: “Clifton’s poetics of understatement—no capitalization, few strong stresses per line, many poems totaling fewer than twenty lines, the sharp rhetorical question—includes the essential only.” Poet Elizabeth Alexander praised Clifton’s ability to write “physically small poems with enormous and profound inner worlds” in the New Yorker.

Faced with a universe gone awry, a time that has tested our humanity, I submit to you, today Blessing the boats.

Subcribe to Poetly to get poetry and commentary in your inbox