“Beautiful, beautiful. Magnificent desolation.”: Poetry and the moon with Mary Ruefle, Sappho, Buzz Aldrin, and Franny Choi

'We pray still. For moon. We answer it now. Ourselves.'

It seeps into our skin, this living. These days that scorch into spring, and tumble out on the other side, as we hold the sky with trellises of flowering trees; visions locked into analogue, and the smear of screen. We live the wave, not the particle. Our teleologies are wrought with the negotiation of a nostalgia, whose only face is the one that is stretched between the experience of individuality, and the ephemeral embrace of community. Even when we are alone, there is the shadow of together. This is what makes ‘lonely in a crowd’, a thing of inconvenience, and solitude, a moment of repose arrived at, not by design, but by that secret knowledge of otherness which can be perceived only in slant, as if one is eavesdropping.

I do not know if these moments are “happy” or “sad”, but that they are birthed when one sees oneself in relation to the world. We chance upon a scrap of time that has floated to the surface, away from the tangle of mind and matter, relationship and war, where an intimacy is forged in the distance between two beings whose isolation allows for a parallelism of desire. I am speaking, of course, of that great lonely cratered ball in the sky, whose light is reflected - the moon.

In poetry, the moon is many things. It is metaphor and mirror, an object of longing, and technology, but from the point of view of the storyteller it is the fulcrum for inarticulable theories of interaction, conversations between things of varied constitution. That the moon is alone is enough. That it is firm, and we are not, creates a vacuum, and this is where meaning surges, when the poet sees this and places their overwhelming presence in the crucible.

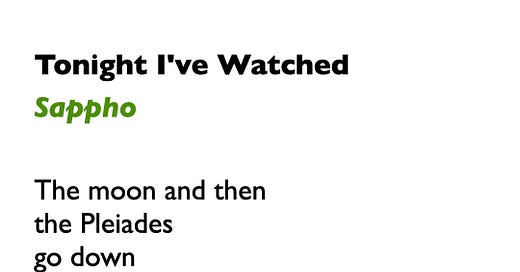

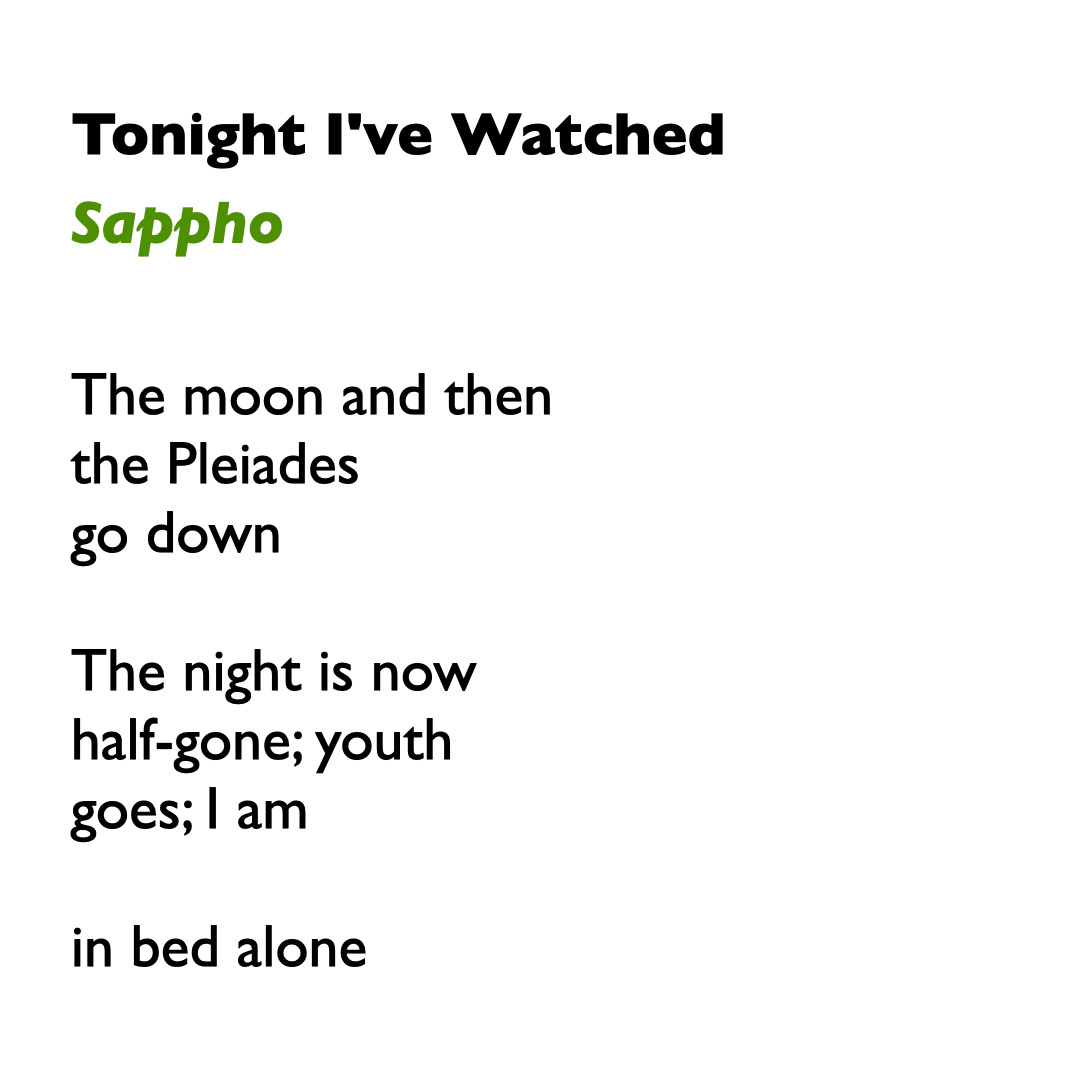

This fragment of poetry is quoted from Mary Ruefle’s Poetry and the Moon, a fascinating essay that explores this question of positionality, and of the moon as motif, and reality. Ruefle notes the ‘pervasive sorrow’ in the poem, and ‘not much struggle to change the order of things’. This leads her to an exploration of the idea of melancholy in poetry. Van Gogh famously spoke about how much more depth, how many strands of colour, resided in melancholy, as placed against a certain flatness of ascent that is joy. But Ruefle sets up a different kind of dialectic here, taking off from Sappho’s poem, and circling back to the question of isolation and blending/communion:

It has been noted many times that there are more sad poems than happy poems in this world, and though I have not fed them all into a computer and read the printout, I would guess that the moon occurs more frequently than the sun as an image in lyric poetry. And I wonder, why? I could start with a dozen reasons: insomnia; the moon’s association with death, one of poetry’s most common themes (yet the moon is equally associated with fertility); or the fact most of the poems in this world have supposedly been written by heterosexual men, who desire women, and the moon is embodied, in so many languages, as a woman, though that’s not universally true— German is one of the notable exceptions. One thing leads to another, one thing cancels another thing out, they are all interconnected, and none of them interest me. After all, it has been proved, using highly sensitive equipment, that even a cup of tea is subject to lunar tides. Let me offer a simple observation. There is a greater contrast between the moon and the night sky than there is between the sun and the daytime sky. And this contrast is more conducive to sorrow, which always separates or isolates itself, than it is to happiness, which always joins or blends.

(Italics mine)

She asks, towards the end of the essay, the essential question, “Is Sappho’s poem, ultimately, one of agitation or repose?”

Going back to the idea of how we see ourselves in relation to a thing, this discussion also dovetails into notions of objectivity, and how our relationships are moderated by ‘otherness’. Ruefle uses the evidence of missions to the moon, how the astronauts responded, what they felt, rather than poetry to understand this phenomena.

Between 1969 and 1972, six missions left for the moon and six missions came back. Not everyone who reads poetry is changed by the experience, nor were all the men who went to the moon forever altered by their vacation. But those who were, without exception, all say the same thing—it was not being on the moon that profoundly affected them as much as it was looking at the earth from the vantage point of the moon. The earth became the Other. You there—me here.

How poignant that moment, when humans set foot on a firmness that is quite different from home. But even then, the journey is perceived as fruitful mainly because of its impossibility, and the assurance of return. The vast swathes of ether, the landscape of solitary darkness, even, when conquered, is beautiful in its mystery.

…I think this is what happens when we look at the moon, and when we write: in each case, two infinitely different experiences are separated by almost nothing, and that very nothing is what is most essential and difficult to maintain. When Buzz Aldrin joined Armstrong on the surface of the moon, his first words were: “Beautiful, beautiful. Magnificent desolation.”

***

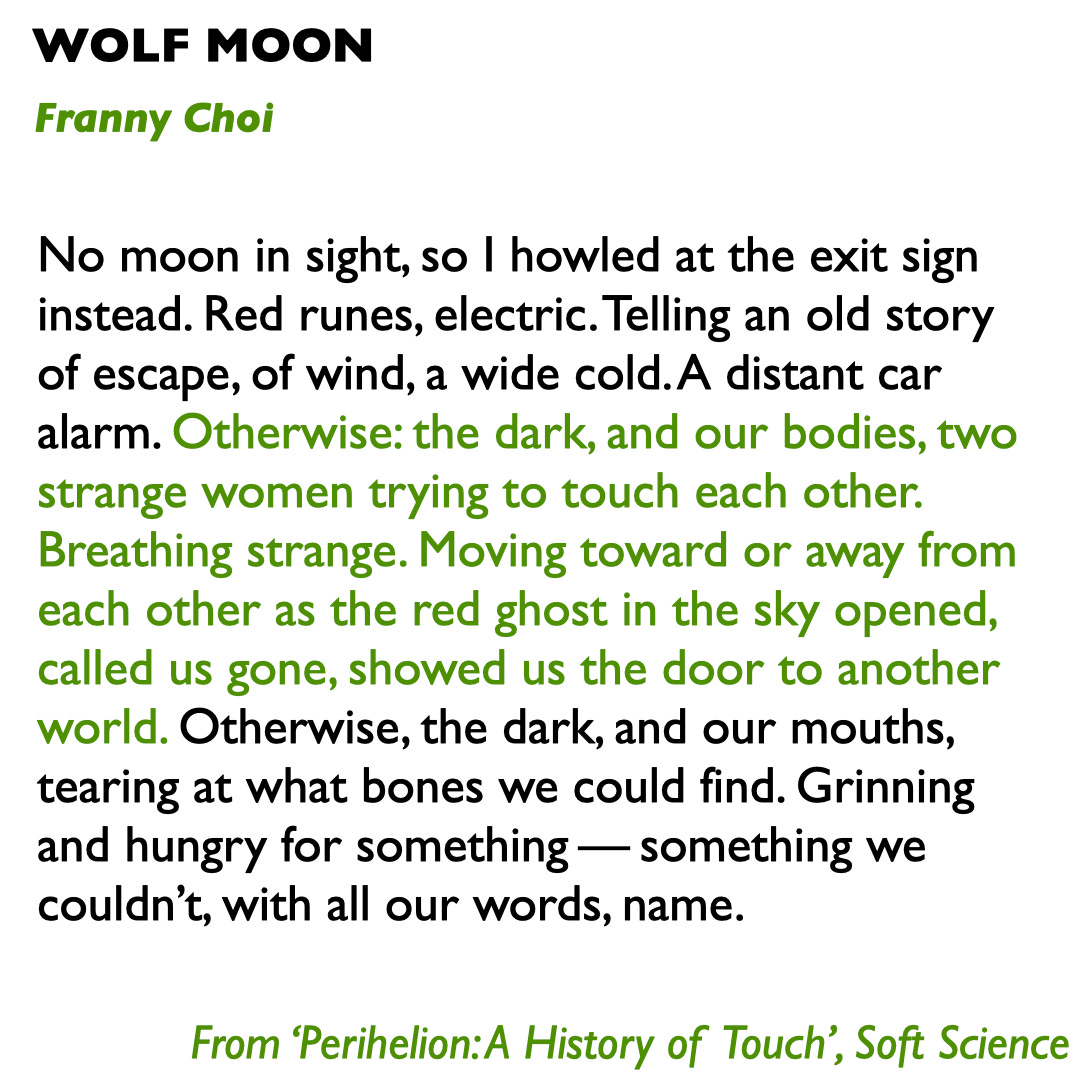

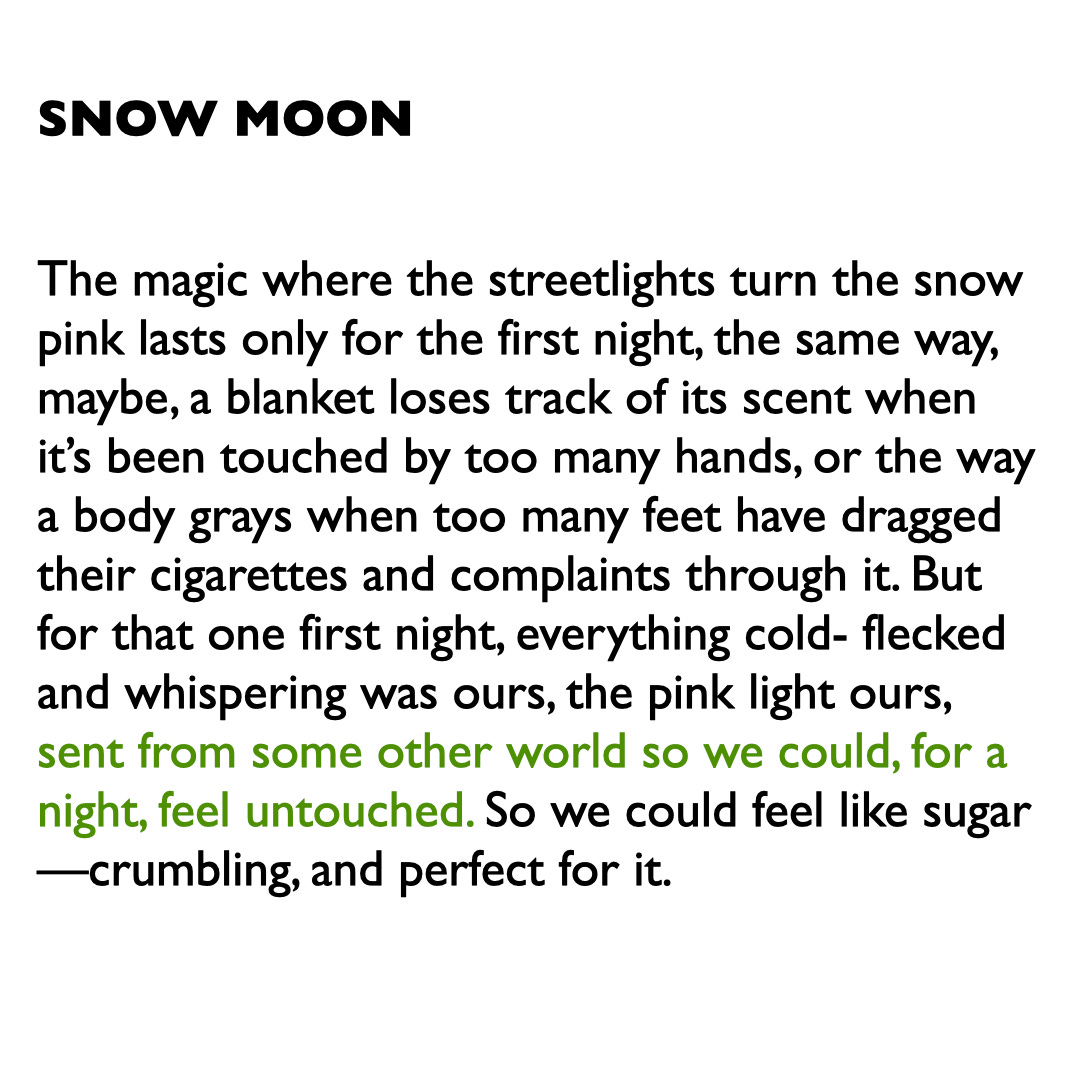

In this magnificent desolation then, touch is the mandavli, the bargain that is struck between the two infinitely different experiences. In Franny Choi’s Perihelion: A History of Touch, from her collection ‘Soft Science’, the moon is both bystander and cleaving host, unreliable observer and perch of quiet vantage. It is present, through, its aloofness. Choi navigates this desolation with surprising intimacy - a study in contrasts in itself - weaving stories of touch and relationship, through neatly set out cross-sections of ‘moontime’. My favourite section of the series of twelve verses with different ‘moons’, each with a distinct tonality, and shared landscape, is the harvest moon. I share with you four excerpts from the poem.

If the poetry, and the commentary, resonate with you, do consider ‘buying me a coffee’.

If the portal isn’t working. Please write to me - poetly@pm.me

(Matlab, if you can’t, that’s also fine, obviously. This will always be a free newsletter)

Note: Those, not in India, who’d like to support the work I do at Poetly, do write to me - poetly@pm.me. (Paypal seems to have left the building, still figuring it out)

You can write to me, waise bhi, if you feel like it :)

Thanks for reading Poetly! Do subscribe if you are not reading this in your inbox. Cheers!