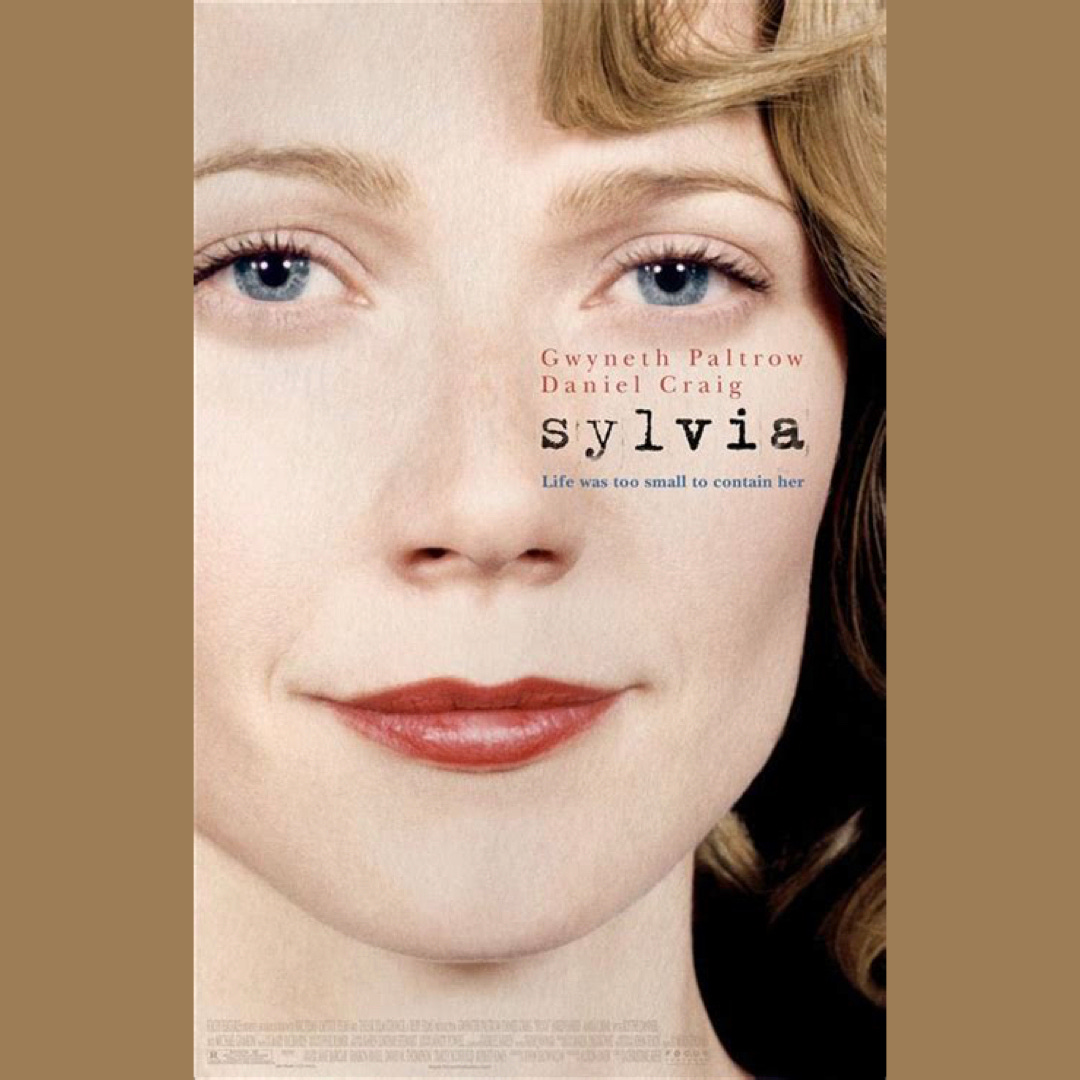

Towards the end of Christine Jeffs’ melodramatic take on Sylvia Plath (Gwyneth Paltrow), after lingering on her inevitable suicide - a moment that the film was palpitating towards - there is a shot of Ted Hughes played by Daniel Craig gazing at a bound manuscript called “Ariel”. Her last anthology, mailed to her unfaithful, estranged lover, was hugely popular, of course, buffeted on by the scandals of her life and her suicide. Nevertheless, at the age of 30, Plath rode on a radical honesty infused with the glistening red of alternating fury and power that many writers writing in the confessional mould could only dream of.

The film, while being a great starting point to the fascinating story of Sylvia Plath, sinks into sensationalism, often painting her fate with reference to her partner, or those around her. Forbidden to use her poetry by Plath’s daughter, the film uses extracts from her work that do convey the gift of wildness and imaginative splendour in melancholy. There are moments in the film that capture the realism of mental illness, but these are rendered in broad Hollywood brush strokes that messily blurt out character arcs or plot points. They do not do justice to the complexity of Plath’s experience, and the people who influenced it.

The two poems I’ve shared below are a glimpse into her haunting spectre of language, her ability to feel and describe sensation with deathly precision, and, as it were to “curate hallucination”. Lowell in his foreword to Ariel observes -

In these poems, written in the last months of her life and often rushed out at the rate of two or three a day, Sylvia Plath becomes herself, becomes something imaginary, newly, wildly and subtly created…one of those super-real, hypnotic, great classical hero- ines. This character is feminine, rather than female, though almost everything we customarily think of as feminine is turned on its head.