A Window to a Dream

with Satyajit Ray's 'Nayak', Gieve Patel's 'The footboard rider' (inflected by Ranjit Hoskote's readings), Forough Farrokhzad's “Window” and Andrea Jurjević's "The Book of Dreams"

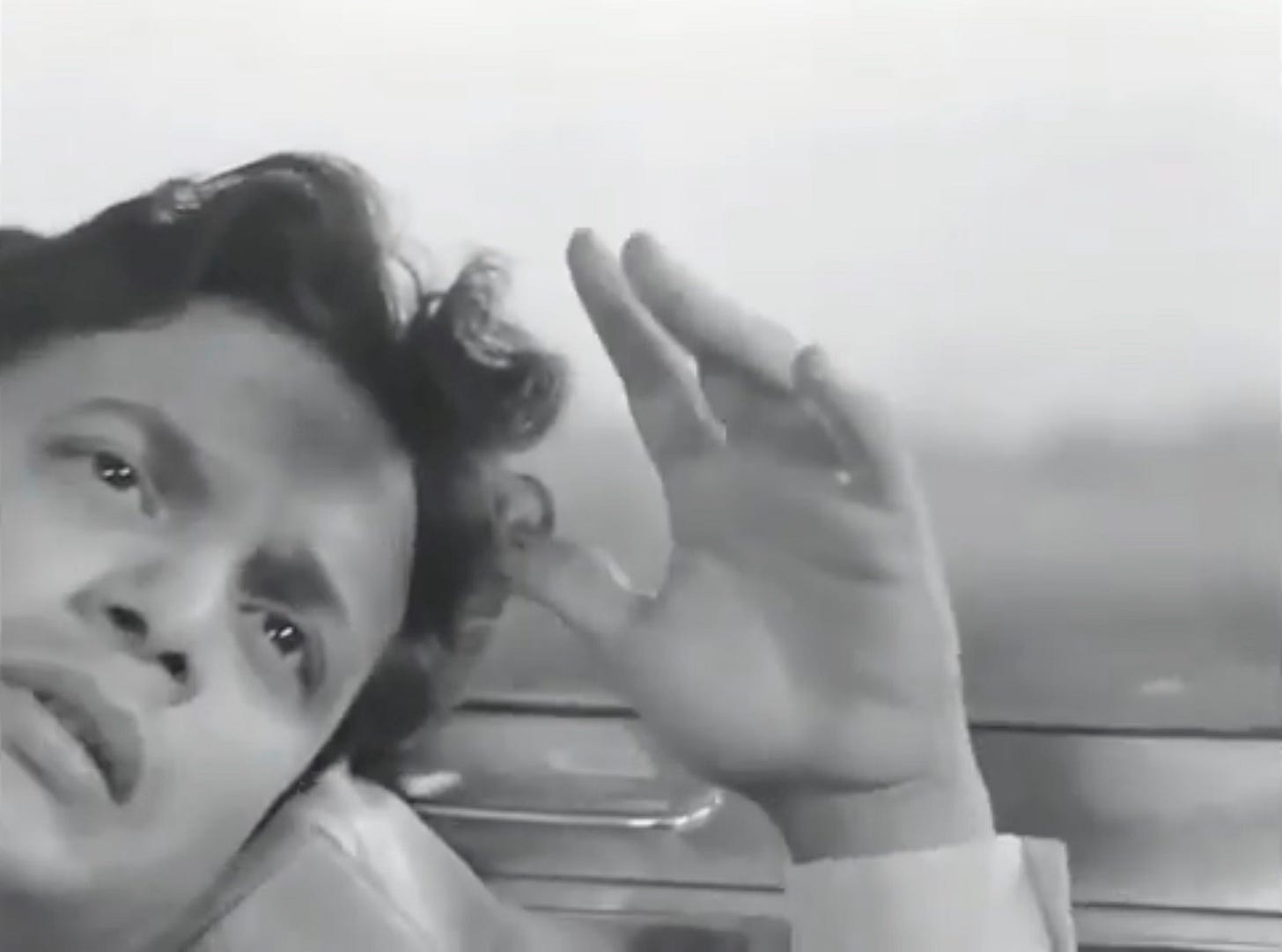

The camera slowly zooms in on the face of a sleeping man. He is handsome - dressed in a suit. You can hear the sound of a moving train - he seems to be resting in a coupe (think 90s sepia lighting). As the frame becomes tighter, slowly but surely closing in on his head and bent shoulders, his left hand flickers, and worry perches on his forehead creasing his eyebrows into a frown. The image fades into his dream - 1000 rupee notes are flying in the air. They fall into a mound. There are many mounds. It is a “desert” of 1000-rupe notes, with piles of notes at regular intervals. The man is smiling, as he walks through the money-scape, thrilled at his good fortune. The background score is glassy - evoking phantasmagoric plucks of a harp, santoor or jaltarang. Money continues to fall from above, making the mounds larger and larger, and the smile on the man’s lips grows wider. Scrooge-like, he gambols in this fantastical excess, throwing the notes in the air, laughing as he climbs and jumps from mound to mound. The music stops. A sombre draught starts and slowly begins to overwhelm the frame. Even the light has dimmed into dusk, now reflecting the gathering solitude of the man’s dreamscape. You hear a telephone ring. The man follows the sound, and as it grows louder, the telephone enters the frame. The man is shocked as he discovers that the handset is placed, not on a keypad, but between the fingers of a skeletal hand. He trips as he hastens away from the surreal vision, and the sound grows faint, only to swell again, louder. Not one, now, but many. Everywhere he looks these ghostly contraptions with handsets at different angles on bony digits bent out of shape, reach upwards out of the note-piles. He runs away only to see many more skeletal hands, where there weren’t any before, many of them without telephone handsets on them. As he wanders around frantically searching for an escape, chants of Govinda set to percussive dholak beats rev to a crescendo, and he falls down. He begins to sink into the quicksand of notes, and neck-deep in money, he tries to pull himself out unsuccessfully. He turns and sees the silhouette of another man sitting cross-legged, calmly, on a mound a few metres away. “Shankarda” he shouts, recognising the man. “Help…Save Me, Shankarda”. The man gets up - he is middle-aged, wearing spectacles, and dressed up like a king. His face appears to be fashioned out of plaster, that is cracking at different places. He extends his decaying hand, but he is unable to save the man, and he balls it steadily back into a fist and retracts it. The man is about to fall right into the unfathomable void, when there is a sound. The scene cuts abruptly to his hand hitting the glass window of the train coupe, forcing his stricken eyes open. The camera moves from his hand plastered to the glass, to his face as his chest heaves with long breaths, pushed out of his soul from the fatal dream-vision of his falling into the money-desert. The frown has vanished into an expression of brief terror, before he orients himself to his surroundings, and pushes himself up on the berth.

What I just described to you is the first dream sequence from Satyajit Ray’s 1996 classic “Nayak: The Hero”. I saw the film for the first time today, at a screening organised by a Delhi film club, Films From Underground. I have wanted to see it for many years, and many of the frames or sequences were familiar (for eg. Uttam Kumar blowing smoke rings, and Sharmila Tagore’s “Aditi” smiling coyly as she snubs the celebrity film star Arindam (Uttam Kumar’s character) and gently mocks his flirtatious smart-alecky comments with dry wit). This dream sequence stayed with me (there are more in the film - If you haven’t seen it, I hope you get a sense of the surreal dream which reflects the protagonist’s subconscious dilemmas about money, fame, and other things). Shankarda, the friend who is unable to save him in the dream is an old mentor and compatriot from his younger days who warned him against entering cinema (he believes it to be a cheapening of the more superior art of “theatre” - the film actor, he says, is a “puppet” in the hands of various marionettes including the director, producer and eventually, the audience).

The sequence is haunting, and Ray’s taut editing (all his films were edited by Dulal Dutta) dramatically juxtaposes the tight frames with wide angles that allow the narrative to seamlessly transition from the protagonist’s internal landscape to the external world, and his presence in the moving train coupe.

The moment when the camera jump-cuts to his hand hitting the window, (from the dream where he is falling into the money-desert)

and then slowly moves to his horrified face,

reminded me of a painting. The image came instantaneously to the mind’s eye, as such imaginings are wont to, dredged involuntarily from memory’s erratic stream.

The painting is by Gieve Patel. Patel’s death in 2023, at the age of 83 still reverberates in the world of art. Those who are familiar with his life’s work might have sampled the exhibition “A Show of Hands | In Memoriam: Gieve Patel” curated by Ranjit Hoskote, where his friends, and fellow artists (including Sudhir Patwardhan, Atul Dodiya, Anju Dodiya, Gulammohammed Sheikh and Jitish Kallat among others) contributed artistic tributes. This painting was first displayed at an exhibition curated by Hoskote in 2017, which drew its title from the eponymous “wraith-like figure” in the painting. I had seen this painting, before, of course. But it was only last year, that I learned of Hoskote’s interpretation of the figure when I attended a book launch (the 2017 catalogue essay is part of the book which brings together 7 essays by Hoskote on Patel’s life and work - To Break and Branch, Seagull Books). In his catalogue essay, entitled Crossing the Bridge of Paradox: Gieve Patel’s ‘Footboard Rider, he describes the protagonist of this painting as one of Patel’s “more spectral dramatis personae [Italics mine]”. He goes on to describe how the figure, caught in the threshold of the inside-outside of the train compartment, (are we outside looking in, or the inside looking out?) “subtly disorients our viewerly certainties”; very much like the viewer of Nayak’s dream sequence.

But the crux of the connection between the two surreal framings (for me) lies in Hoskote’s interpretation that casts the “Footboard rider” as a possible character in the sleeping man’s dream: “The longer we look at the painting, the more we are drawn into its reverie-like mood, and the less certain we grow of our bearings. The train’s interior begins to resemble its exterior; we cannot tell where sunrise ends and dusk begins, or where inside passes into outside. And the footboard rider: is he real, within the framework of the painting, or is he simply a phantasm in a dream that has possessed the sleeping figure? [Italics mine]”. I had not thought of the figure in that way, when I first saw the painting, so this interpretation opened a new way of thinking about the work.

Once my mind had made the connection, it sedimented among other associations as I watched the rest of the film. There are other dream sequences, drenched in the dazzle of the Nayak and his fascination with the mysterious “formidable”, “modern woman” (a Sharmila Tagore who is devastating in the avatar of a pioneering feminist journalist at her confident, witty, and vulnerable best who gives it back to the clearly smitten celebrity film star).

I am fascinated by dreams and artistic portrayals of dreams. I wake up sometimes, jotting down the gifts of reverie, in the anxiety-stricken moments where friends or family members say and do things, or attempt to rescue me from danger, the way Shankarda attempted to pull out Arindam. In a film which self-reflexively talks of the nature of fame, cinematic production, and the heady universe of the film industry, dreams slip alongside the camera’s gaze, and trip into the arena of the viewer’s meaning making.

There are many “dream-poems” and “window poems” which similarly slip into the subconscious imaginative realm, pulling out motives and anxieties that are hidden deep underground. In the introductory essay that describes his friendship with Patel, Hoskote writes:

I will never forget the advice he gave me when, as a young poet, I went to him with my anxieties about the directions opening before me: “To write truly meaningful poetry, you have to go deep down, to where things are broken.”

Perhaps you could keep these thoughts in your mind, as you read the two poems that I share with you today.

The first is a poem by Forough Farrokhzad called “Window”, translated from the Persian by Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr. The poem is a part of her compilation of translations of selected poems, entitled Let us Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season.

Farrokhzad’s voice ruffles across the leaves of time - from more than half a century ago - in that strident defiance that has become a beacon of the changing contemporary political landscape that gave birth to this modern idiom in Persian poetry (“She had changed Persian poetry”, Gray declares, at one point in her translator’s introduction, referencing a published poem about uninhibited desire) This unapologetic conviction in a female speaker had not been a part of the mystic lovers’ trope that was historically everpresent.

But even these are broader strokes - listen instead to the gathering images in this piece, and you see layered glimpses of the individual caught in a tumultuous history that their expression actually shaped, with a visceral force. “..when you arrive at the moon/ write the history of the mass murder of flowers…”. Poetic testimony grants the poet her “share of the leaves of history”. All she needs is a “window”: “A window for seeing/ A window for hearing/ A window like a well” (Cue Gieve Patel’s “wells” of cloudy skies and blossoms - “cosmic intimations” (Hoskote, 2017) ) One window is enough for the poet, who is caught in the vortex of a town where they were “chopping up the heart” of her “lamps”, and from the “agitated temples” of her “desire”, “spurts of blood were scattering everywhere”. Astride the relentless juggernaut of the time, in the throes of a micro-history that engulfs a country’s movement into modernity, the poet finds resolve: “I realized I must, I must, I must/ love madly”.

The second poem I share with you today is more recent. It is by the Croatian poet Andrea Jurjević. “The Book of Dreams” is a part of her 2024 collection, In Another Country, winner of the 2022 Saturnalia Books Prize (published by Saturnalia Books, March 2024).

“The moon that’s the stone lodged in the throat of the night” is the image that took my breath away. The particular metaphor reminds me of an old Sampurna Chattarji poem - I cannot recollect the line, but it was from a poem in her early collection Absent Muses. I remember that poem had a revolutionary tonality, and the metaphors rendered voice differently from the way they are rendered in this poem. Here, the images of wildness, nature and the crowd convulse across the body and the changing landscape of a ferocious spirit that is at once strange, familiar and present (“I have a need for closed captions when I talk to people”). The moon returns again and again, changed every time. The energy of the poem is best captured by choice that verbs “winter” in the last verse. The last line delivers the parting shot, with a reverberating echo (also giving the name to the entire collection). “I wake seasick from the sloshing veins/ In another country I’m rain” [Italics mine].

Note: The Book of Dreams was featured on Poetry Daily last August. From an assessment of In Another Country, by poet and art historian Roberto Tejada, featured on the website: "I was instantly enveloped by the night-tide logic of the poems, their unruly image-making, and their commitment to the 'department of dream justice,' so to speak.”

….Anyway, bohot ho gaya na… aaj keliye….

Thankyou for reading :)

I trust that you are finding meaning, and the space to create. Do write to poetly@pm.me if you have any questions, queries, or comments. I will write back as soon as I find the space, and the time.

If you like what you read, do consider ‘buying me a coffee’.