“Not everybody needs to be a brave person, there is place for cowards in this world”

- Perumal Murugan in an interview after the release of his collection “Songs of a Coward”

Perumal Murugan’s aspect, like his poetry, reminds me of an ancient, gnarled tree - a wrinkled monument that has been seen many storms, many droughts, a tree whose roots reach deep into the earth, hiding in its womb a secret of silence. As Murugan released a video expressing his solidarity for the farmers through a song that has been put to music by TM Krishna, I could sense the quiet persistence of this tree’s laboured breathing. Murugan speaks with the simplicity and gravity of one who understands the struggle of the farmer, the plight of those whose voices have been dismissed by the state. His protest isn’t loud and fierce like many of the popular voices that have dominated the headlines, it is the humble tribute of a man who had once announced his own obituary as a writer, and come back to life on the wings of poetry.

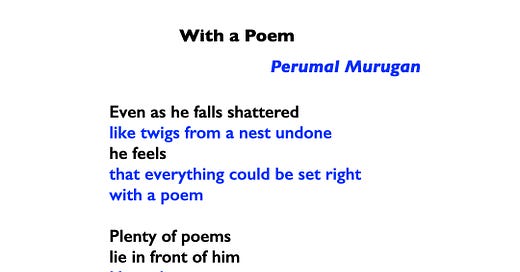

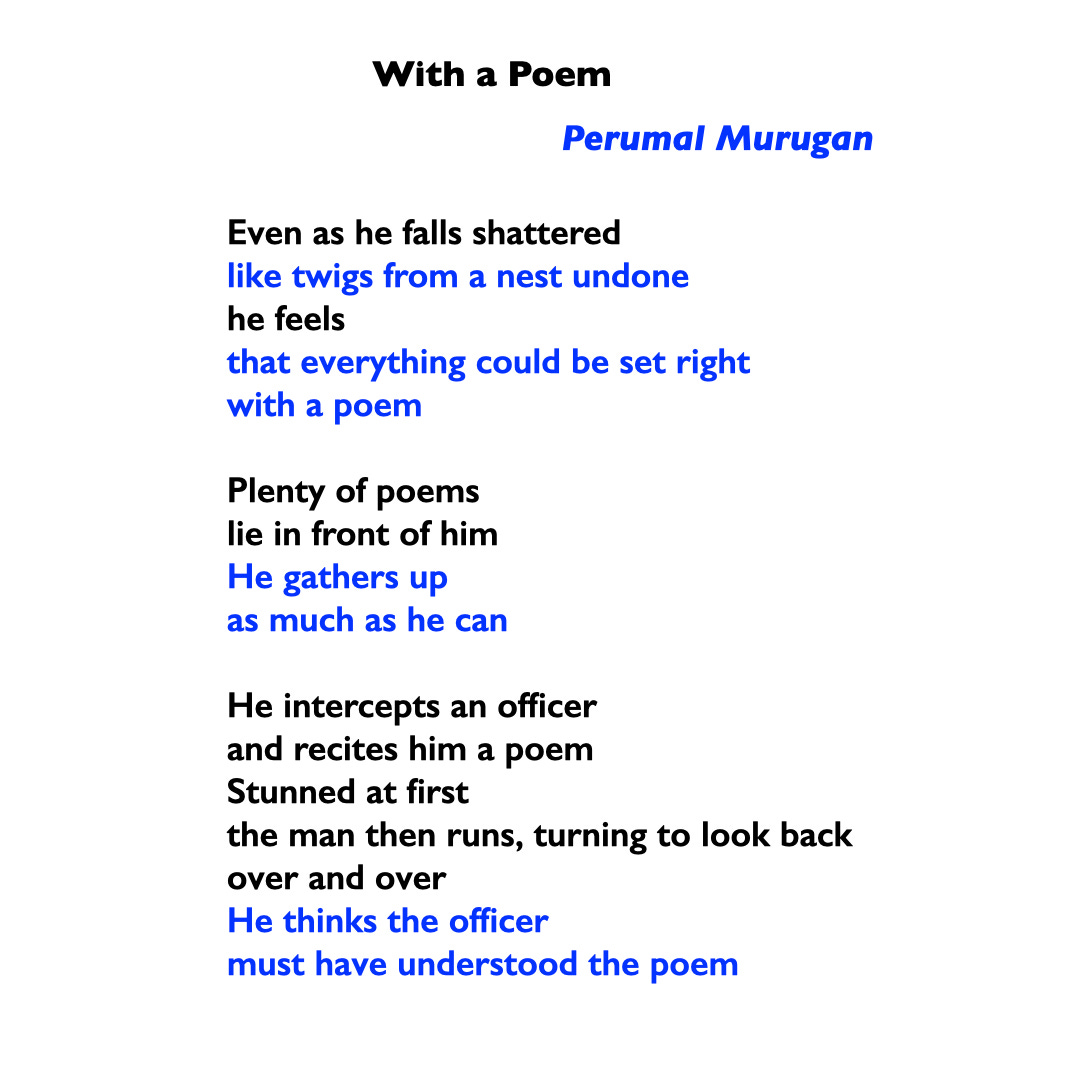

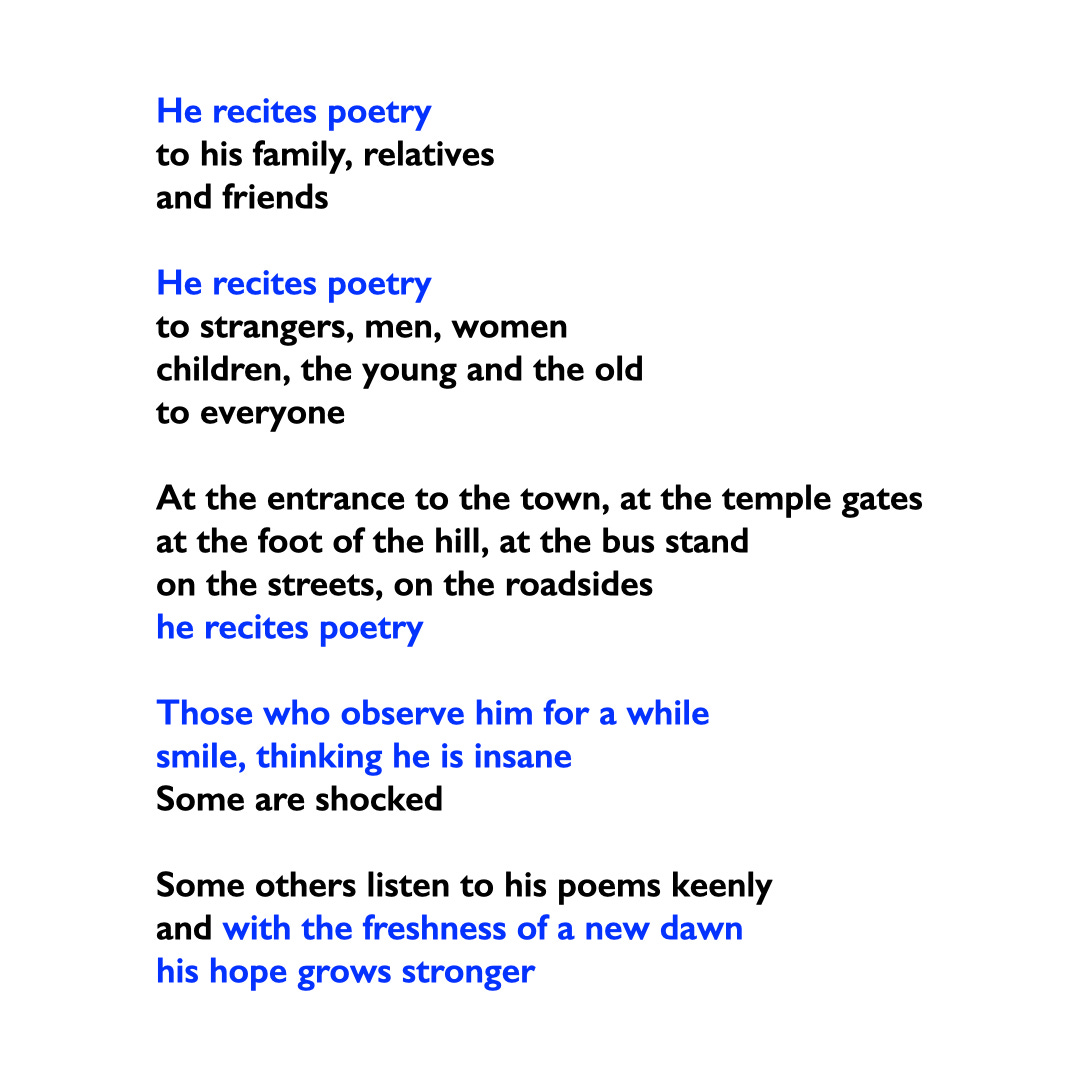

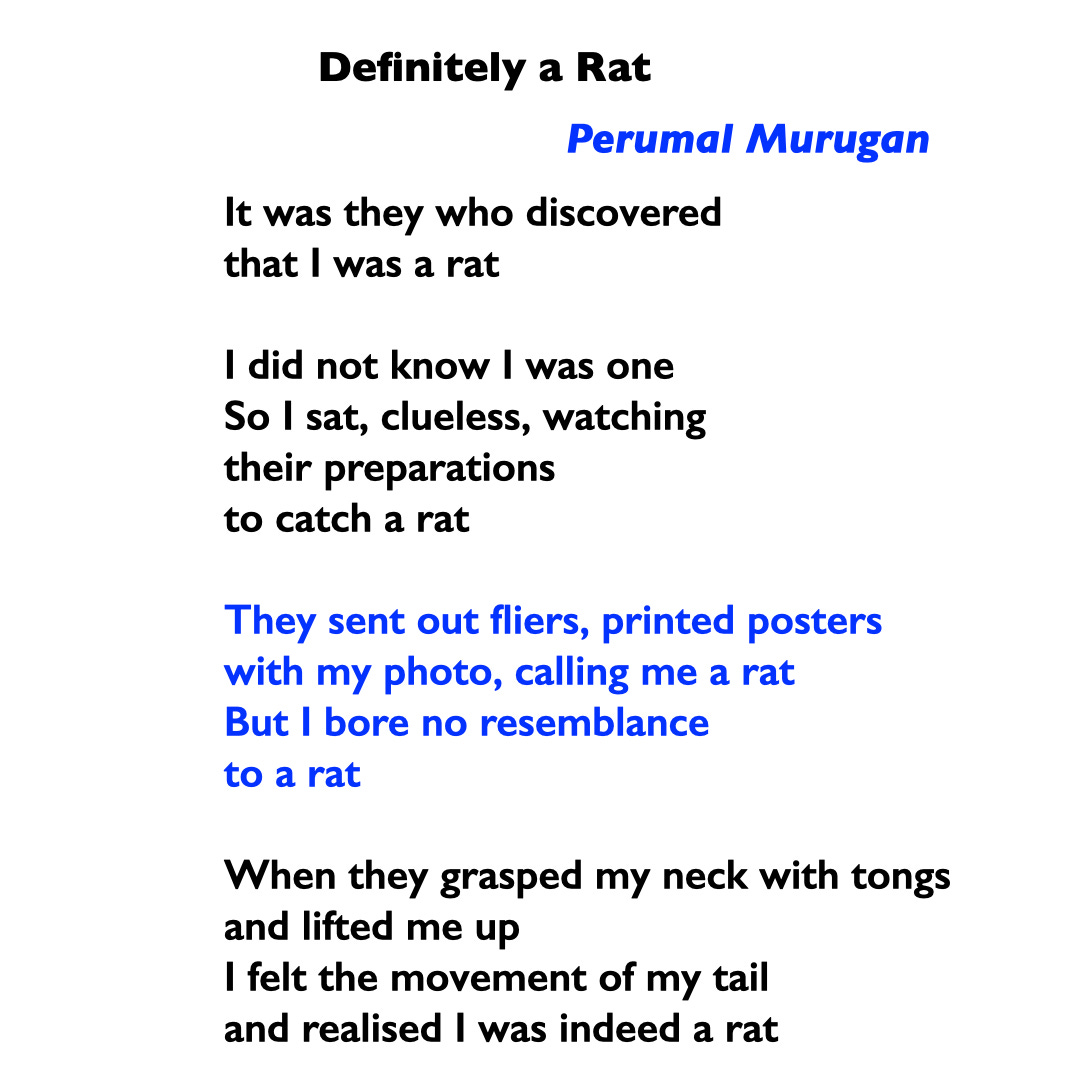

I have been reading the dark, intense words poems of Murugan’s ‘Songs of a Coward’ - an anthology of poetry that signalled his return to writing after being hounded by right wing groups, threatened with censorship, violence and death threats, made to leave his hometown, and being repeatedly called a coward and scoundrel. The High Court’s refusal to ban his book that described a fictionalised custom based on myth and local traditions, was a breath of fresh air in these trying times. One wonders, if Murugan would receive the same honour today.

Rising from the pages of this anthology is like waking up from the belly of a dark, beastly dream. Murugan’s world is upside down. He is a “Lab rat”, spread-eagled, examined, dehumanised. He enters the body of a “guinea pig poisoned to death”. He is the poet who talks to himself, and recites poetry to anybody who’d listen.

I am fascinated with the coiled energy in Murugan’s pen. There is no fanfare, no clinching moment of victory, only testimony. The sharp, biting irony of his thoughts are laid out in a matter-of-fact, perfunctory tone. He writes poetry with the resignation, and quiet resolve of a sweeper who has the task of cleaning the central square of a village that sees a million footsteps through the day. The deepest, most secret crevices of his anxieties, hopes and convictions are described with precise detail. The poem that gives the book its title, suggests a kind of resistance, a reinterpretation of notions of valour and bravado. It question the very category of bravery. Inherent in his questioning is a critique of privilege, of status quo, of “royal” or “mythic” frames of reference that do not measure up to the narratives of resistance that are needed today.

In his own words:

“I am familiar with dryland agriculture. I know how to take cattle to graze…however, writing is my true vocation…Poetry is a great medicine, a rare herb. It was poetry that revived me.”